Thursday Mar 12, 2026

Thursday Mar 12, 2026

Wednesday, 31 December 2025 00:30 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

When Ditwah ripped through bridges, buried tracks, and crippled services, it did not cause a crisis. It revealed one that had been a disaster waiting to happen

Cyclone Ditwah didn’t simply wash away Sri Lanka’s railway tracks. It washed away our excuses.

Cyclone Ditwah didn’t simply wash away Sri Lanka’s railway tracks. It washed away our excuses.

For decades, Sri Lanka Railways (SLR) has been the classic state-owned paradox: socially vital, fiscally fragile, structurally neglected – and politically untouchable. When Ditwah ripped through bridges, buried tracks, and crippled services, it did not cause a crisis. It revealed one that had been a disaster waiting to happen.

Now, in the dismaying aftermath, the real question is not how fast we will rebuild the railway. It is what kind of railway we choose to rebuild. And whether we are bold enough to move from patchwork repairs to structural change.

The backbone we forgot

The former Ceylon Government Railway (CGR) is not only a nostalgic colonial relic. It was also paradoxically a working system: 1,593 kilometres of national track linking regions, livelihoods, and opportunities.

In 2023 alone, SLR transported 109.15 million passengers and moved nearly 1.99 million tons of freight, generating total revenue of approximately Rs. 16,079 million. But its operating and capital expenditures were over Rs. 38,983 million, leaving the system mired in persistent deficits.

And in a country squeezed by fuel imports (Sri Lanka spends billions of dollars annually on such imports), congested roads and climate shocks, rail is the cheapest, cleanest, and most socially inclusive mass transport available.

Yet it has been starved of investment while expected to act as a welfare instrument, a jobs program, and a political soundbite for successive administrations keen to be perceived as ‘people-friendly’ and supportive of public sector jobs – all at once.

Revenue has lagged lamentably and unacceptably far behind running costs. Rollingstock has aged dismally. Signalling systems have stayed obsolete. Many stations (some of them colonial relicts, others modern monstrosities) have decayed. Drainage, bridges, culverts, cuttings, tunnels, embankments, and stations were not built for the climate or ecological context we now live in.

Then Ditwah arrived. And decimated the network.

When climate meets neglect

The cyclone hit the railway like the Down Express at full tilt. Large sections of the network were knocked out. Lines were twisted, embankments washed away, bridges weakened. Landslides blocked mountain stretches – especially along the sections of the Main Line between Kandy and Badulla, where slopes gave way and foundations were undermined.

The cyclone hit the railway like the Down Express at full tilt. Large sections of the network were knocked out. Lines were twisted, embankments washed away, bridges weakened. Landslides blocked mountain stretches – especially along the sections of the Main Line between Kandy and Badulla, where slopes gave way and foundations were undermined.

At the peak of the disruption, only around 30% of the network was operational, meaning that roughly 478 kilometres of track remained usable.

In the aftermath, Government reports documented 91 places where tracks were damaged, 73 bridges were affected, and dozens of culverts and smaller stations impaired.

Even weeks later, operations limped back in phases – prioritising high-demand corridors, although stranded regulars would disagree – while hill country and secondary segments remained under repair. By late December 2025, about 69% (1,098 km) of the network had resumed services.

This is not simply a story of cyclone-induced damage. It is a story of infrastructure designed for yesterday’s climate, maintained with yesterday’s budgets, managed with yesterday’s institutions – and expected somehow to survive today’s and tomorrow’s storms.

The estimates are sobering. Restoring the damaged rail infrastructure alone is projected to cost about $ 400 million – only to bring the network back to pre-storm functionality.

But that figure does not include broader network modernisation or investments to make the system resilient to future climate shocks.

And spending that kind of money merely to return to fragility would be the most expensive mistake we could make.

The trap we must avoid

Beyond SLR, Sri Lanka at large faces a familiar temptation after every disaster:

We repair what failed – instead of asking why it failed. We pour money into the visible (tracks, sleepers, bridges) while ignoring the invisible: governance, incentives, project delivery discipline, and long-term planning.

We repair what failed – instead of asking why it failed. We pour money into the visible (tracks, sleepers, bridges) while ignoring the invisible: governance, incentives, project delivery discipline, and long-term planning.

If we follow that script again, Ditwah will become just another chapter in a long book titled “Missed Opportunities”.

Because the truth is blunt: the system was already failing. The cyclone only cleared the fog.

The devastating tropical storm laid bare three structural weaknesses:

1. Infrastructure built for another era

Much of SLR’s physical network dates back more than a century, with incremental upgrades that have never matched the pace of demand or climate risk.

Drainage channels are inadequate for torrential rainfall, slopes remain unstable, and bridges were not retrofitted for higher flood loads. Signalling systems lag decades behind peer systems, contributing to inefficiencies and safety risks.

So then when extreme weather hits, damage multiplies.

That vulnerability is not unique to Sri Lanka. But it is avoidable for an island nation that has long hovered on the cusp of being dragged into the 21st century.

Railways in other countries in the South Asian region have strengthened embankments, installed modern drainage, and retrofitted bridges to withstand heavier rainfall patterns. Why not here?

2. Institutional and financial fragility

SLR’s fiscal gaps were apparent long before Ditwah.

The railway department earned Rs. 16,079 million in revenue in 2023, but its total expenditures (operational plus capital expenses) were Rs. 38,983 million – a structural deficit that forced repeated reliance on governmental subventions.

Chronic funding shortfalls have translated into deferred maintenance, dilapidated infrastructure and limited capacity to invest in automation, digital systems, or modern rollingstock.

Political micromanagement distorts priorities and delays projects. Procurement is slow, fragmented, and vulnerable to interference. Capital spending is inconsistent. It is a system asked to deliver modern outcomes – with 20th century rules and 19th century infrastructure.

3. Poor passenger experience

Operational inefficiencies such as infrequent services, delays, overcrowding, and unreliable booking systems have eroded public confidence. Tourists don’t come for unpredictable timetables; freight operators shift to roads.

Operational inefficiencies such as infrequent services, delays, overcrowding, and unreliable booking systems have eroded public confidence. Tourists don’t come for unpredictable timetables; freight operators shift to roads.

Commuters adapt, but confidence erodes.

This is not a marginal inconvenience. It is a subtraction from national productivity, a drag on tourism revenues, and an incentive for more polluting modes of transport.

The fork in the track

We have only two choices. We can reconstruct the railway so that it looks like it did on the day before Ditwah. Or we can rebuild it so that it survives the storm that comes after the next Ditwah.

That means treating rail not as a sentimental asset – but as critical national infrastructure that supports economic growth, disaster resilience, climate strategy, and social mobility.

It also means recognising that ‘business as usual’ will guarantee failure.

What rebuilding should really mean

Rebuilding must be about resilience, governance, and smarter partnerships – not simply concrete and steel.

Build for the climate we have

Embankments, culverts, bridges, drainage, slopes – everything must be redesigned to withstand heavier rainfall, rising water tables, and landslide risk. Detailed climate risk mapping should drive investment, not political geography.

Every rupee spent on resilience now saves multiples later. We cannot afford to rebuild weak.

Reform how the railway is governed

A more autonomous rail authority with clear mandates, ring-fenced budgets, real performance targets, and transparent procurement is not a luxury. It is the only way to ensure continuity across governments, avoid stop-start projects such as the much vaunted, arbitrarily abandoned and now resurrected (?) Light Rail Transit (LRT) project – and reduce political foot dragging.

Accountability is itself resilience.

Fund strategically, not episodically

Multi-year capital planning, resilience funds, and contingency financing must become the norm. We can also expand revenue beyond fares – through commercial leases, logistics hubs, advertising, and station retail – reducing pressure on the state budget.

Fares can be rationalised carefully and gradually, and paired with targeted subsidies, so essential mobility is preserved.

The goal is not necessarily profit. The goal is definitely sustainability.

Where the private sector fits – and where it doesn’t

The debate over public-private partnerships (PPPs) is often ideological. It should be practical.

PPPs are not about ‘selling our railway.’ They are about using private expertise and capital where it actually helps – under strict guardrails.

For example:

Sri Lanka already has PPP experience. There are some 179 PPP projects valued at $ 5.3 billion across ports, energy, and infrastructure. This indicates an existing legal framework that could extend to rail projects.

At the same time, the State must remain responsible for core network stewardship, safety regulation, and long-term planning.

Done badly, PPPs privatise gains and socialise losses. Done well, they can speed timelines, reduce costs, and raise standards.

The difference lies entirely in governance.

Innovation isn’t optional

Sri Lanka cannot modernise its railway while treating it as a museum.

Predictive maintenance using sensors and real-time data, passenger information systems, reliable e-ticketing, digital asset management – these are not futuristic add-ons. They reduce breakdowns, cut costs, and build trust now.

Academic research already demonstrates the potential of IoT-based systems to optimise maintenance and operations in Sri Lankan rail contexts.

Some of this innovation will come from local tech firms, others from global partnerships. All of it requires one thing we lack: institutional readiness to adopt and manage change.

We should start small, pilot quickly, learn fast – and scale what works.

Counting the costs honestly

There is bad news. Recovery will not be cheap. But if it is to be done, and it has to be, it can and must be done well, meaningfully and realistically.

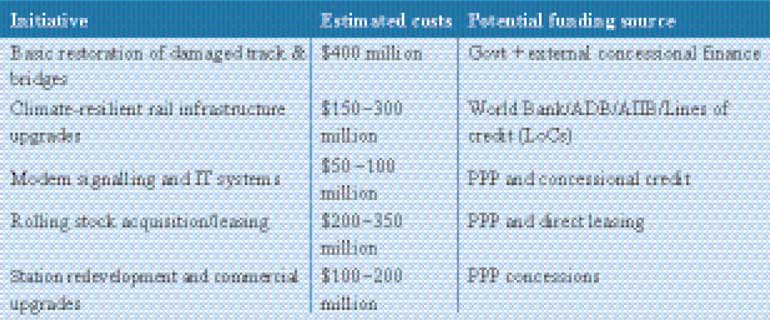

Here is a rough but arguably realistically projected breakdown of present needs as indicated by research:

These figures span infrastructure, resilience, technology, and commercial upgrades – and are not mutually exclusive. They represent a comprehensive vision, not a limited repair budget.

The real comparison is not between spending and saving. It is between spending now – or paying repeatedly in lost productivity, higher road congestion, oil imports, avoidable accidents, service collapses, and yet another round of emergency repairs after the next extreme weather event.

Rail is not an expense line. It is a risk-reduction strategy, an economic enabler, and a social equaliser.

The politics of courage

Every reform flagged here is politically difficult.

Autonomous authorities reduce ministerial discretion. Transparent procurement challenges entrenched interests. PPP guardrails frustrate rent-seekers. Careful fare reform invites controversy.

But the alternative is a cycle of decay that punishes the poor the most, drains the national budget, and traps the country in perpetual reactive mode.

Savvy political leadership in the present context means saying plainly:

A test of national seriousness

How Sri Lanka treats its railway after Ditwah is a proxy for something greater than good governance alone. It is a proof yet to be demonstrated whether the country as a whole is willing to move from reactive crisis management to strategic, sustainable, long-term thinking.

We cannot keep waiting for disasters to justify reforms we already know are necessary.

We know the infrastructure was fragile. We know the governance model was outdated. We know climate shocks will intensify. We know rail is indispensable.

So, the case for change is not technical. It is moral, ethical, and practical.

A system worth building

Imagine a network that:

This is not utopian. Countries poorer than Sri Lanka have done it. Countries with worse starting points have done it.

The difference is not money. It is discipline, continuity, and the refusal to treat disaster recovery as a paint job.

The window will close

Cyclone Ditwah has created an unusual alignment: public awareness, donor attention, and political necessity. That alignment will not last.

Reform delayed will be reform denied. If we simply patch, clear debris, and declare victory, we will have wasted the most valuable asset a crisis can give: legitimacy for change. One that was promised, and one for which a cardinal opportunity was delivered by fate, karma, chance, destiny, the curse of Kuveni. Take your pick – and pick up the slack.

Don’t rebuild – redesign

Sri Lanka stands at a railroad junction.

Only one of those tracks leads out of crisis.

Cyclone Ditwah forced us to stop. What we choose to lay next – rails, rules, and responsibilities – will decide whether the next generation inherits a resilient national asset or another fragile repair bill.

This time, we should not merely get Sri Lanka Railways back on track. We should lay a better track altogether.

(The writer is Editor-at-large of LMD.)