Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday, 28 June 2021 00:05 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The lush greenery tea plantation before going for organic in 2012 (Photo Credit – Lalith Liyanage)

The fungus-attacked tea roots after using compost fertilisers

Tea plot invaded by weeds after using the composts

|

| Planter Lalith Liyanage

|

Lalith Liyanage: Daring intrapreneur

Planter Lalith Liyanage of the Hidellana Tea Factory fame is a daring entrepreneur cum intrapreneur. An entrepreneur will look at the market and exploit market opportunities to make profits. An intrapreneur will improve processes within the business and make it

stronger, more viable, and more profitable.

As an entrepreneur, following his father’s footsteps, he went into low country tea growing after leaving college, because that was a very profitable business given the advantage of the brand name Ceylon Tea and the high yields that he would get by converting virgin land into glossily green tea plantations. At that time, there was the Tea Smallholder Development Project, implemented jointly by the Ministry of Plantations Industry and the Central Bank out of the funds loaned by the Asian Development Bank.

In this entrepreneurial activity, he followed the standard technical advice given to tea growers by the country’s Tea Research Institute that entailed the use of appropriate chemical fertilisers and approved weedicides and pesticides in correct amounts.

In 2012, as an intrapreneur, he sought to produce organic tea to the niche market by converting two blocks of his tea land into organic fields fertilised by composted materials. Organic tea fetched a premium price because it was demanded by consumers who were prepared to pay a higher price because of its claimed health benefits. If the experiment was successful, Liyanage’s plan was to convert all his tea plantations into organic plantations and become a supplier of a premium tea product to the global markets. That would have paved the way for other organic tea lovers to enter the business.

Flash decision to ban chemical fertilisers and pesticides

Flash decision to ban chemical fertilisers and pesticides

President Gotabaya Rajapaksa made a flash decision to convert the whole of Sri Lanka to an organic land by banning the importation of chemical fertilisers and pesticides. With that, there is a frenzied interest in the country to make plantation crops too fully organic compliant. This is specifically relevant to tea because it was always marketed as a health drink.

In the early years of tea promotion in the mid-19th century, billboards in London grocery shops urged consumers to drink Ceylon tea because it was a brain tonic. Later, the range of health benefits was expanded to cover ageing, diabetes, heart diseases, arthritis, nervous disorders, and cancers, to mention but a few.

On top of these claimed health benefits, if an organic tea is supplied to the market, it will surely catch up like a wildfire. It will be a quantum leap for Ceylon tea which is experiencing difficulties in penetrating new markets due to competition from other producing countries. Given the long-time taken by a country to make its produce organic-compliant, Sri Lanka, if it starts now, will have a competitive edge over its competitors at least for a dozen years. In this context, Liyanage by intrapreneur-ing into organic tea production has made a yeoman service to rescue the country’s ailing tea industry.

Learning points from Liyanage’s experiment

His experiences are therefore learning points for others who are vociferous about organic tea without knowing the real challenges that must be faced. Over several telephone calls and exchange of emails, Liyanage narrated his story to me. That story is presented here not to discourage the prospective organic farmers but to help them appreciate the difficulties which they would face and problems which they should resolve in their path to organic cultivation.

Liyanage says that he ventured into organic tea cultivation and production in 2012 with two small plots that were added to organic farming in two stages. In the first stage, it was the conversion of a 10-year-old tea plot of 1.21 ha (about 3 acres) in extent. In the second stage, an additional 1.61 ha (about 4 acres) were allocated for organic farming. This second plot is linked to a tourist hotel owned by him on the premises promoting tea-tourism. Hundreds of tourists from all over the world stay in this hotel just to get a first-hand experience in the production of their favourite drink. Though the organic sector is not giving him profits, this tourism segment has compensated for the loss.

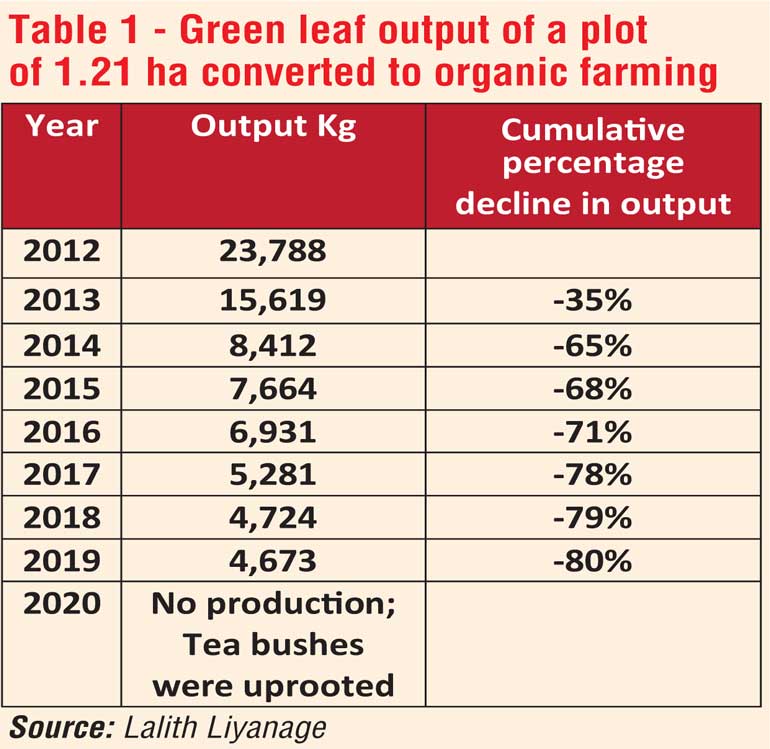

Since the first stage plot already had 10-year-old tea bushes, it can be used to compare the crop ‘before and after’ going to organic farming.

Winner of the National Plantation Award

Before going organic in 2012, it was traditional chemical fertilisers and weedicides that had been used on this first plot. They have been used in accordance with the instructions given by TRI to tea growers. With those input uses, the 1.21 ha farm had produced 23,788 kg of green leaf in 2012. This had amounted to 661 kg per acre per month. This was a high yield and Liyanage says that in that year, this plot had received the National Plantation Award from the Ministry of Plantations for this excellent performance. After going organic, to get the best results, drip irrigation water sprinklers were installed in this plot.

Reduction in yields after composting

Reduction in yields after composting

However, the use of organic fertilisers had resulted in a continuous drop in the yield as shown in Table 1. Accordingly, within one year of denying chemical fertilisers and weedicides to tea bushes, the yield declined by 35% to 15,619 kg. The drop of yield was so sharp in the following years, by 2019, it had fallen to 4,673 kg, a level lower by 80% than the original level of production in 2012.

Liyanage says that he had to encounter a double whammy after he had started using organic fertilisers. Because of the working of pests in the composted fertilisers, the roots of his tea bushes had had a fungus attack causing them to decay. Since there was no suitable fungicide to tackle the problem and the plantation had by that time become totally unprofitable, tea bushes were uprooted in 2020. Now the soil has to be rehabilitated for at least three years before he can go for a new cycle of planting. A tea bush, if continuously pruned and appropriate fertilisers and weedicides are applied, can have a lifespan of about 100 years. But Liyanage’s organic plants had such a short life, they had to be uprooted within 20 years.

TRI: Use 20,000 kg of compost fertiliser per hectare of tea lands

In June 2021, TRI has issued guidelines in Sinhala for use of compost in tea cultivations (available at: https://www.tri.lk/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/GL_01_2021_Sinhala.pdf ). According to TRI, when producing compost for tea plants, urban waste or human excreta should not be used. The quality of the compost should be improved to maintain the required composition of phosphorus, carbon, nitrogen, potassium, magnesium, and calcium.

The content of heavy metals such as cadmium, chromium, copper, lead, mercury, nickel, and zinc should not exceed the levels prescribed by the Sri Lanka Standards Institution. Hence, the most appropriate inputs are leaves, grasses, straws, animal excreta, etc., that do not contain hazardous heavy metals.

TRI’s recommendation has been to use per annum 10 metric tons compost fertiliser per hectare in upcountry plantations, and 20 metric tons per hectare in mid and low country plantations. These organic fertilisers are not cheap and according to the estimates of TRI, it will cost about Rs. 11.40 to produce one kg. What this means is that an upcountry tea grower has to spend annually about Rs. 114,000 to fertilise 1 hectare, and a mid and low country grower about Rs. 228,000 – double that amount – if he produces his own composts.

If he buys it from the market, there are the problems of quality assurance, price, regular supply, and transportation. These problems could be minimised to some extent if, as TRI has recommended, composts are mixed with chemical fertilisers, a system of hybrid application. But it will cause tea to lose its organic feature and therefore could not be marketed under that brand.

Chemical fertiliser use is much lower

Chemical fertiliser use is much lower

TRI has also advised smallholders as to how they should use chemical fertilisers in the low, mid, and Uva ranges (available at: https://www.tri.lk/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/TRI_Advisory_Circulars_SP_10e_Jul2016.pdf ). Noting that in this region, the soil organic matter, magnesium and sulphur levels are low, to get the best yield, TRI has recommended the use of fertilisers rich with these components. Accordingly, two new fertiliser mixtures, U834 and UT752, have been recommended.

Farmers at present use about 150 kg of chemical fertilisers in four rounds a year per acre. Without the Government subsidy, a 50 kg bag will be around Rs. 4,000, and the annual cost of fertilisers will be around Rs. 120,000 for chemical fertilisers as against the estimated cost of up to Rs. 300,000 for compost fertilisers. If chemical fertilisers can yield 20,000 kg per Ha, the fertiliser cost of a kilogram of green leaves will be around Rs. 6.

High cost of composts

I asked Liyanage whether compost fertilisers were freely available for use in his region. His answer was that they were not available freely and when they were available, there was the problem of quality assurance. The quality of these composts varied from one consignment to another. The quality tests are expensive and cannot be done for every consignment. Hence, tea smallholders are at the mercy of suppliers if they choose to apply organic fertilisers to their fields.

On top of this, the price of composts at about Rs. 12-15 per kg is prohibitively high; at these prices, the tea growers have to spend between Rs. 120,000 to Rs. 150,000 per annum in the upcountry region, and between Rs. 240,000 to Rs. 300,000 in the low and the mid regions. If a plot of 1 Ha yields about 8,900 kg of green leaves, the fertiliser cost per kg alone will amount to Rs. 27 to Rs. 34 in the case of mid and low country region and Rs. 13 to Rs. 17 in the case of upcountry plantations. Unless the price of green leaves is increased to accommodate this high cost, it is unavoidable that tea smallholders would become bankrupt.

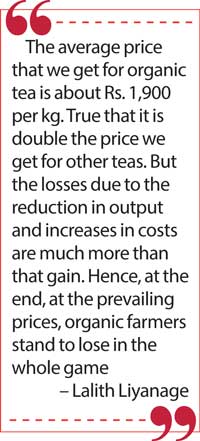

Organic tea needs a subsidy

But organic tea fetches a premium price and that price should surely compensate for any loss. I asked Liyanage about this. “The average price that we get for organic tea is about Rs. 1,900 per kg. True that it is double the price we get for other teas. But the losses due to the reduction in output and increases in costs are much more than that gain. Hence, at the end, at the prevailing prices, organic farmers stand to lose in the whole game,” he says. What this means is that unless the Government gives a subsidy, the organic tea production cannot sustain itself.

Composts lead to weeds and fungus attacks

Liyanage says that there are two other problems which organic farmers of tea will face. Compost fertilisers carry seeds of unknown weeds. Once the composts are applied to the fields, these seeds germinate covering the entire field. If composts are treated with chemicals to kill these seeds, they would affect the normal organic transformation of the composts involved. This is not what is expected of organic farming. How these weeds have invaded the tea cultivation maintained by Liyanage after the use of untreated organic fertilisers is shown in the photograph.

The other problem is the attack of fungi on tea bushes due to changes in the moisture levels in composts. Since there was no treatment for these fungus attacks, Liyanage had to uproot his entire cultivation after 20 years of planting. This is not a cost which any tea grower can afford. The photo in this article shows how these fungus attacks have decayed the root system of tea plants in his cultivation.

Wrong diagnosis by TRI?

I asked him whether he brought these issues to the attention of TRI. “I did, but they are also not in a position to help growers since the complexities arising from organic farming have not been identified yet. Regarding the fungus attack, the diagnosis of the field officer who visited the cultivation was that it had been due to wrong pruning of plants. I do not agree with that diagnosis because I have pruned my other cultivations too in the same manner. They have not been affected by any fungus attack,” says Liyanage.

What about the new weeds invading the plantations? I asked him. “That is a critical problem,” he replied. “If we use labour to weed them out, we have to spend a fortune for that; if we use weedicide, we will lose the organic certificate; if we do not use either one, we will lose the entire cultivation.”

What this means is that TRI must embark on an accelerated research program to tackle the weed problem arising from using compost fertilisers.

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

Thus, organic farming of tea is good because of the higher price and the claimed health benefits. But it is bad due to decline in output, enormous costs, and consequential losses. It is also ugly because of the invasion of unwanted weeds and untreatable fungus attacks.

(The writer, a former Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka can be reached at [email protected].)