Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Friday, 16 June 2023 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Shiranee Yasaratne, Moderator: Arun Dias-Bandaranaike, Amal Nanayakkara, Deepal Wickremasinghe, Prema Cooray, Channa Daswatte and Ravi De Silva at the Panel

Prema Cooray

By Surya Vishwa

The story of a hotel project once mired in public wrath, at a time unused to start any major tourism venture of the blue-chip category.

How does one negotiate between nature and humans? How does one pitch for a world-class tourism initiative while safeguarding the socio-environmental, cultural and traditional interests of village based communities in a world where such charm is fast eroding?

How can a nation trapped between two bloody sagas- a Marxist insurgency and a civil war, unleash a Sri Lanka tourism venture that would be the first of its ambitious kind? How does a Lankan Blue chip conglomerate do this? Having started such a venture, how can it dispel the vast fear psychosis in the country that reaches the highest political level, alleging environmental and cultural destruction? How can one dispel such allegations and transform a protestor into a colleague? How can one bring tourists into a country aflame with a civil war and bomb blasts in the city? How can one bring employment to the village holistically through tourism, without upsetting the delicate balance between culture, tradition and development?

How can one resurrect tourism for a heavily invested hotel after the capital Colombo gets shattered by a terror attack targeting the Central Bank of the nation? Amidst every possible obstacle, how could one promote Sri Lanka as a tourism hot spot?

These are intriguing questions.

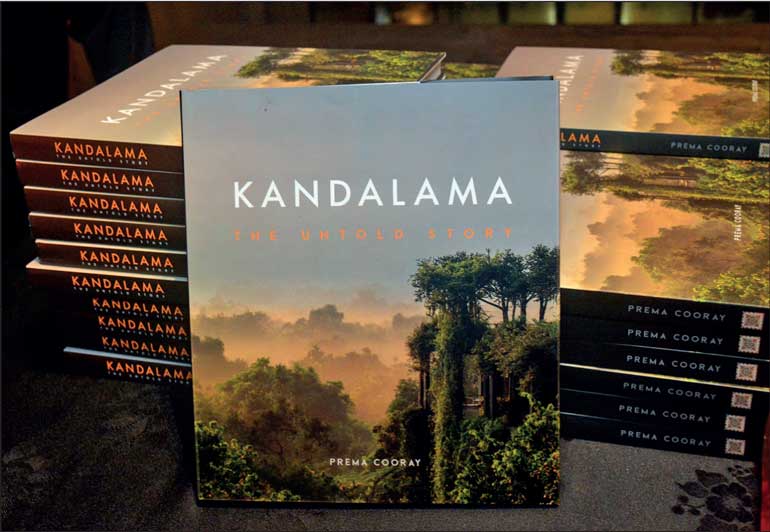

The answers are found in the newly launched book, titled Kandalama: The Untold Story authored by Prema Cooray, the immediate past Chairman of Aitken Spence PLC. Prema Cooray with over 30 years’ experience in the travel and tourism industry tells what the Kandalama hotel walls would, only if walls could speak.

The book was launched at the Cinnamon Grand Hotel last week amid a gathering including those of the hotel industry, the realm of architecture, policy makers, the academia and media.

The book was launched at the Cinnamon Grand Hotel last week amid a gathering including those of the hotel industry, the realm of architecture, policy makers, the academia and media.

The author notes in the preface how in 1989 Sri Lanka struggled to bring in 195,000 tourists from a high of 410,000 tourists in 1981, showing the drastic economic impact after the July 1983 calamity that changed the stability of the nation. As a strategic response Aitken Spence decided to develop the tourism potential of the 5 heritage sites situated close to each other and from the access point of Dambulla.

He states further:

“The project was going to cost a colossal Rs. 550 million, which is three times the profit Aitken Spence earned in a year during the years 1992 – 1994.”

“The hotel was built without incurring any debt and opened its doors in July 1994 following which the Government changed hands and Mrs. Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga took control.”

The book is attractive as a coffee table book that takes the reader across over four decades to the mid-1980s and earlier to trace the beginnings of the tourism industry in the country and the socio-political impacts.

The book shares the story how with the start of the civil war, under the leadership of Michael Lloyd Mack and his team, Aitken Spence decided to fully commit to the development of the cultural triangle and the idea was born for the Kandalama hotel.

Yet, what was idealistically begun ran into serious difficulty and misunderstanding with the local community.

“The local and international message conveyed was that an environmentally unsuitable project which would erode local culture was beginning to take shape, recalled Prema Cooray, sharing his recollections with the audience who graced the book launch.

In one of its opening pages the book says; “Kandalama would be the first major hotel project anywhere in Sri Lanka in nearly a decade after the country’s civil war was ignited by the communal riots of 1983. Investors had fled amidst little hope for the country’s tourism industry and had stayed away during the Marxist JVP insurrection 1989/90.”

This segment captures the background in which the private sector had to operate at the time.

Under the title ‘A Blue Chip’s vision to expand the tourism horizon,’ the book continues:

“The year was 1991. The highly diversified leisure rich blue chip Aitken Spence was mulling on embarking on yet another ambitious and pioneering venture in the leisure sector. This time it was to be a novel addition to the Group - a five star hotel in the Cultural triangle.”

The book points out that Aitken Spence saw the grand opportunity to be a pioneer, even at a time when it was bleak for tourism.

By the time Kandalama was planned and designed by the iconic Sri Lankan architect, Deshamanya Geoffrey Bawa, the country’s woes continued in the form of civil war, the impact of which were felt primarily in the North-East, but also in the capital Colombo in the form of bomb blasts carried out by the LTTE.

The strategies the hotel management adopted in getting tourists and also in winning public trust for the hotel project seems a study of course material on how to surmount challenges rationally and with emotional intelligence.

With the wide-scale protests at the time against the construction of the Kandalama hotel, with environmentalists, the clergy and political entities joining in, at one point it seemed as though the project would have to be stalled or permanently shelved. What finally won the day was an open invitation to all those opposing, to visit the construction site and later the hotel to clarify for themselves anything they wished to know and ask any questions. The clergy members, villagers and others were encouraged to visit the project site and later the hotel for any inspection and discussion with any official. “This transparency is maintained to date,” Prema Cooray told his audience at the launch.

Ravi De Silva the Aitken Spence Project Manager, a villager himself reminisced the chaotic days where protestors carried out sit-ins with placards.

“I was from the village and I joined the protestors, to observe who attended and how it was organised.”

“I was told that we tried to destroy the village culture with the vice of tourism. I was asked what would happen when Western tourists start sun-bathing in skimpy clothes.”

The fear psychosis that the village modesty would be assailed by “Western culture,” was soon proven totally unfounded as was the allegations that the project would ruin the natural environment.

The Kandalama Hotel triumphed over allegations, proving to be a champion of cultural heritage as it would the preservation of nature.

Among the unique environment protecting architectural steps taken by Bawa included the preserving of natural rock as well as a Nuga tree variety; and allowing rainwater to flow off the rocks and under the hotel, to the reservoir. The columns around the building and the rooftop were designed to support the growth of foliage from the surrounding environs and the state-of- the-art technology based waste recycling and aeration plant were mechanisms that made the village community and all critics realise that instead of ruining the environment, the hotel was contributing to safeguard it while providing much needed jobs to the village youth.

Among the unique environment protecting architectural steps taken by Bawa included the preserving of natural rock as well as a Nuga tree variety; and allowing rainwater to flow off the rocks and under the hotel, to the reservoir. The columns around the building and the rooftop were designed to support the growth of foliage from the surrounding environs and the state-of- the-art technology based waste recycling and aeration plant were mechanisms that made the village community and all critics realise that instead of ruining the environment, the hotel was contributing to safeguard it while providing much needed jobs to the village youth.

The hotel, since its inception has won several local and international awards for its environment friendly practices and among the most prestigious recognition awarded to its architect is the Agatha Khan award given only to a select few of the world’s leading architects.

Meanwhile, an ironic factor which marks the hotel’s imprint into the life of the community is how the young protestors who went with their parents to protest and who as adults seeking jobs elsewhere and not finding were recruited by the hotel.

However, by 1996 although the hotel was ready for occupation the Central Bank bomb blast turned out to be an unexpected blow. Facing the crisis head-on the hotel management succeeded in weaning tourists back to the country and the hotel by taking a strategic decision to negotiate with a Maldives tourism operator linked to Aitkin Spence. It was explained by the hotel team at the launch ceremony, where those associated with Kandalama spoke of the experiences of the time, that this had proved to be a stellar success and the Italian market strand that commenced with the Maldivian tourism link continues to be strong in Kandalama.

Overall, in its eighteen chapters and 270 pages, Kandalama: The Untold Story, brings life to Geoffrey Bawa’s masterpiece with photographs, Bawa’s original sketches and designs and firsthand narrations of those involved in the epic journey of a Blue Chip Tourism venture that accurately read the pulse of nature and the community.

Hence, Prema Cooray’s book is a testimony of courage, team spirit, innovation and transparency of a major step to revive the economy through tourism at a time when doing so was almost a utopian dream.

The book provides much insight into Sri Lanka’s tourism industry as it navigates fresh challenges in the current post pandemic and economic crisis realities.

Cooray’s storytelling style takes the reader on the journey of Kandalama, the recent history of Sri Lanka, while celebrating the selfless service of many people in diverse professional circuits who were part of its odyssey. The book is dedicated to architect Milroy Perera, a close associate of Bawa.

Among those featured in the book as having shared the journey of Kandalama include: Channa Daswatte, Chairman, Geoffrey Bawa Trust, Michael Mack who took over the responsibilities of Aitken Spence in 1991, Ratna Sivaratnam who played a major role in propelling forward Aitken Spence Tourism and Travel in the 1970s, members of the Board of Management of Kandalama, Dilshan Fernando who worked on designs as a team member of Bawa, Amila de Mel and other architects in Bawa’s team. Also mentioned with gratitude is Dulanjali Jayakody (then Dulanjali Premadasa) who played a key role in speaking to her father, Ranasinghe Premadasa to alleviate some of the opposition to the hotel.

“My father saw clearly that Kandalama fitted perfectly into his model of rural development and was very anxious that the project be completed speedily. He took a map and drew a half kilometre circle around Kandalama and asked Aitken Spence to source their daily produce requirements from the neighbourhood. He said if this was insufficient, to expand the circle further,” Dulanjali is quoted as saying. It is pointed out that when the Court of Appeal ruled against the project, President Premadasa issued a Presidential Proclamation by virtue of the powers of the Constitution, authorising the transfer of the land to Aitken Spence. He also sent the famed engineer, Dr. A. N. S. Kulasinghe to approve the ramp, as there were questions whether the ramp encroached into the lake reservation.

“My father saw clearly that Kandalama fitted perfectly into his model of rural development and was very anxious that the project be completed speedily. He took a map and drew a half kilometre circle around Kandalama and asked Aitken Spence to source their daily produce requirements from the neighbourhood. He said if this was insufficient, to expand the circle further,” Dulanjali is quoted as saying. It is pointed out that when the Court of Appeal ruled against the project, President Premadasa issued a Presidential Proclamation by virtue of the powers of the Constitution, authorising the transfer of the land to Aitken Spence. He also sent the famed engineer, Dr. A. N. S. Kulasinghe to approve the ramp, as there were questions whether the ramp encroached into the lake reservation.

The book shows how the hotel contributed to the village with youth recruitment, produce purchase, transport contracts and such other requirements being obtained from within the vicinity. A factual account of community services ranging from the development of schools, sports, is cited in the book.

The creation of learning and development clusters by the hotel enabled systematic routes of engaging with the youth of the area to facilitate their educational and career goals. The authenticity of this contribution is reflected in how the lives of those such as Ranjith Kumarasinghe from Dambulla were changed for the better. Ranjith, three decades ago was the head prefect at Tennakoon Central College and lacked two points in his exam results to enter university. The book narrates how he joined the hotel staff, as did many other youth. Ranjith emerged as the Human Resources Manager of the Kandalama hotel and was responsible for learning and creating development opportunities for the village youth.

The book ends with the awards and accolades the hotel received, including the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) green building accolade developed by the US Green Building Council. Other awards received by Kandalama include the Green Globe 21 award winner, the Asia Pacific Travel Association award (PATA), the CNNs Ultimate Service award, the World Travel and Tourism Council award, among many more, and thereby becoming Sri Lanka’s most awarded hotel.

The media played a major role in supporting the hotel in its time of adversity and two senior journalists associated with the hotel and the tourism industry as a whole; Ravi Ladduwahetty and Niresh Eliatamby have been honoured in the book for their professional support.

Pix by Upul Abayasekara