Tuesday Mar 10, 2026

Tuesday Mar 10, 2026

Wednesday, 19 January 2022 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Debasish Roy Chowdhury

John Keane

By Chandani Kirinde

India is hailed as the world’s largest democracy, which since independence from British colonial rule in 1947, has held onto the principle of one person, one vote to elect its rulers amidst numerous

India is hailed as the world’s largest democracy, which since independence from British colonial rule in 1947, has held onto the principle of one person, one vote to elect its rulers amidst numerous

challenges. Through regular use of the ballot, millions of Indians have kept faith in democracy while many of its neighbouring nations have faltered over the post-independence period moving between military and autocratic rule.

But in the current political scenario, there are growing concerns among Indians as well as internationally that the country’s elected rulers are wavering from the principles of democracy that are enshrined in the country’s constitution and the guiding principles of the nation’s founding fathers who advocated a pluralistic, tolerant society in a country of over a billion where a myriad mix of people live in relative peace and harmony, bound by their Indianness than been divided by their individual identities based on ethnicity, religion, caste, class and many other distinctions.

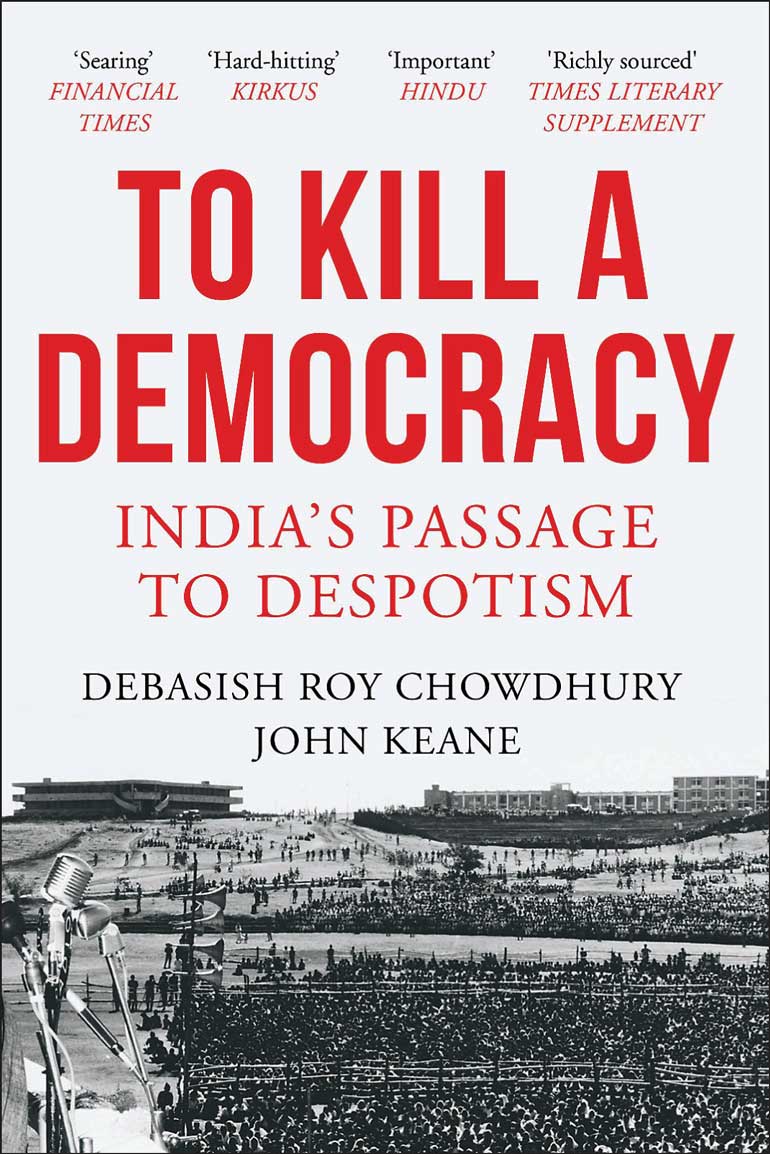

But is all what pluralistic secular India stood for beginning to die as the current rulers of the country are consolidating hardline Hindu rule at the expense of its minorities putting democracy on shaky ground and paving the way for despotism? It is this deeply troubling question about the future of India’s democracy that has come under scrutiny by Debasish Roy Chowdhury and John Keane in their recent publication “To Kill A Democracy – India’s Passage to Despotism” published by the Oxford University Press.

Debasish Roy Chowdhury is an Indian journalist based in Hong Kong and has written extensively on Indian politics, society and geopolitics and John Keane is Professor of Politics at the University of Sydney and the WZB (Berlin).

Since India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s famous “tryst with destiny’ speech on 14 August, 1947 when the country’s tricolour flag was hoisted replacing the Union Jack ending 200 years of British rule, the path was laid for the people of the newly independent nation to choose their leaders and live under democratic rule. Seeking to soothe the fury of his compatriots over India’s partition, Nehru called on them to desist from ill will and blaming others but to ‘build the noble mansion of free India where all her children may dwell.’

In “To Kill A Democracy – India’s Passage to Despotism”, the authors look at the historical background leading to the birth of the Republic of India, the adoption of the country’s constitution on 26 November 1949 in the preamble to which India is described as a ‘sovereign democracy republic’. It was within the visionary constitutional framework which stands for social, economic and political justice for all citizens as well as guarantees of liberty of thought, expression, freedom, belief, faith and worship, equality of status and opportunity, that the country’s first parliamentary election was held in October 1951. This allowed Indians to elect their rulers and paved the way for people’s participation in the democratic process, one that continues till today.

The path of democracy has not always been an easy one to tread and successive governments since independence have tested the people’s mandate but have always relented under public pressure.

Debasish Roy Chowdhury and John Keane in their book detail the challenges to India’s democracy the country has faced in the past seven and half decades and focus on the health of India’s democracy under the current Prime Minister Narendra Modi who was first elected to this office in May 2014 and re-elected in 2019.

The authors argue that the decomposition of India’s social life and the breakdown of democracy cannot be laid only at the feet of Modi but has been a trend that has been decades in the making. The books draw from statistics and case studies on a state-by-state basis to show that social disparities in the country have remained high and have become more evident during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic but also focuses on the backsliding on democratic rule since Modi’s election as Prime Minister and the slide of the country towards despotism.

“Despotism isn’t old-fashioned tyranny or military dictatorship, or describable as a single-ruler horror show the ancients called autocracy. It mustn’t be confused with 20th-century fascism or totalitarianism. Despotism is rather a new type of strong state led by a demagogue and run by state and corporate oligarchs with the help of pliant journalists and docile judges, a top-down form of government that has the backing of not just the law-enforcement agencies but also the backing of millions of loyal subjects who are willing to lend their support to leaders who offer them tangible benefits and daringly rule in the name of ‘democracy’ and ‘the sovereign people’,” the authors write.

They reiterate that while it is tempting to say Modi alone is responsible for the slide away from democracy, the “brute fact is the cupboards of Indian politics have long been stocked with determined and power-greedy figures like him” and the killing a democracy and building despotism always requires bigmouthed demagogues, political bosses who play the role of earthly avatars of ‘the people’. “Narendra Modi, arguably the biggest big boss in Indian politics since Independence, takes things further. His popularity seems immune to the most egregious failures of his government – be it a whimsical and painful currency ban, or a poorly thought-out lockdown, a crashing economy, heart-wrenching epic migration by distressed workers, or even loss of territory and soldiers to China. It’s almost like he has transcended to a celestial plane of power far removed from the usual rules of politics.”

So, in this background, is Indian democracy nearing the end of its life then? That is the question raised by the authors at the conclusion, but the answer is also not clear cut nor is the future bleak as there are many indications that the spirit and substance of democracy are still very much alive in India.

“Given the profound social decay and government corruption in today’s India, it would be tempting to conclude that the democratic spirit of equality and institutions designed to prevent bossing and bullying of citizens and their everyday lives don’t stand a chance. But India doesn’t lend itself to simple, reductive conclusions. That means, when the going gets really rough, democracy fosters hope against hope. It stirs up insurrections. It gives energy to the sense that it’s possible to change things, to build a better future guided by precious precepts: no famine and slavery, more freedom with clean running water, better schooling and decent healthcare, greater social equality, less political bossing and bullying. In moments when democracy falls sick, this is perhaps its most important virtue: it inspires citizens to take full advantage of what they have, and what comes their way, to build a better future for everybody, not just for the rich and powerful few.”

Co-author Debasish Roy Chowdhury has also lived and worked in Calcutta, Sao Paulo, Hua Hin, Bangkok and Beijing, and reported from Sri Lanka, the Philippines, Nepal and Qatar. He is a Jefferson Fellow and a recipient of multiple media prizes, including the Human Rights Press Award, the Society of Publishers in Asia (SOPA) award and the Hong Kong News Award. He writes for TIME Magazine, the South China Morning Post, Haaretz and The Washington Times, among others.

Co-author John Keane is renowned globally for his creative thinking about politics, communications and democracy, and is the author of a number of distinguished books including The Life and Death of Democracy (Simon & Schuster, 2009), Democracy and Media Decadence (2013), When Trees Fall, Monkeys Scatter (2017) and The New Despotism (Harvard University Press, 2020). He was nominated for the 2021 Balzan Prize and the Holberg Prize for outstanding global contributions to the human sciences.