Thursday Mar 12, 2026

Thursday Mar 12, 2026

Saturday, 17 January 2026 00:55 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

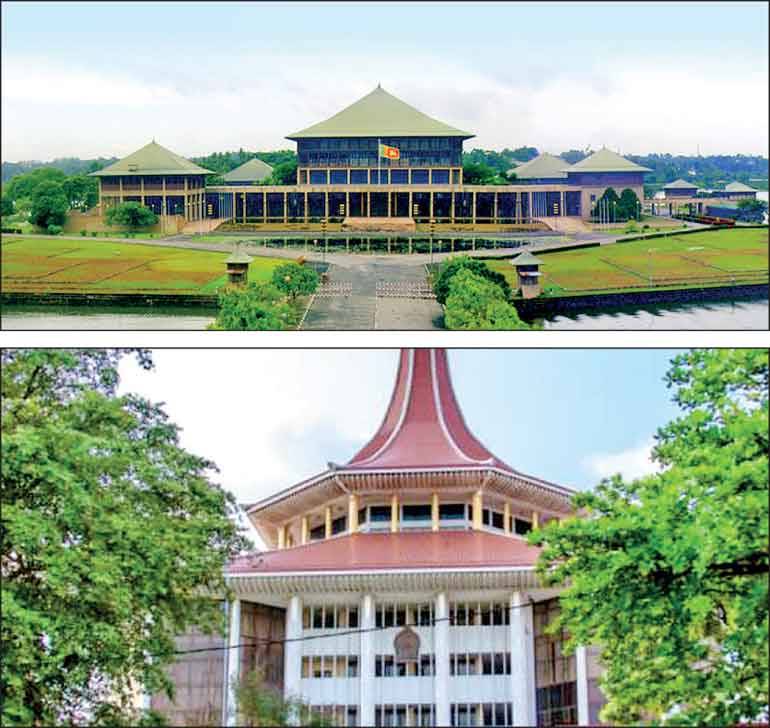

IT was reported that Speaker Jagath Wickramaratne has rejected a motion submitted to him by 31 Members of Parliament requesting the appointment of a Select Committee of Parliament to examine the exercise by the Judicial Service Commission of its powers relating to “the appointment, promotion, transfer, dismissal, and disciplinary control” of judicial officers. The reason for the rejection of the motion, as stated by him, is that compliance with the motion “would be a derogation of the independence of the judiciary and thereby a derogation of the judicial power of the People”. It is the view of Speaker Wickremaratne that the Judicial Service Commission “exercises the judicial power of the People”. That, I submit, is the fundamental flaw in the Speaker’s ruling.

IT was reported that Speaker Jagath Wickramaratne has rejected a motion submitted to him by 31 Members of Parliament requesting the appointment of a Select Committee of Parliament to examine the exercise by the Judicial Service Commission of its powers relating to “the appointment, promotion, transfer, dismissal, and disciplinary control” of judicial officers. The reason for the rejection of the motion, as stated by him, is that compliance with the motion “would be a derogation of the independence of the judiciary and thereby a derogation of the judicial power of the People”. It is the view of Speaker Wickremaratne that the Judicial Service Commission “exercises the judicial power of the People”. That, I submit, is the fundamental flaw in the Speaker’s ruling.

The Queen v. Liyanage

As far back as 1962, in the case of The Queen v. Liyanage, (Trial at Bar No.1 of 1962), the Supreme Court comprising Justice T.S. Fernando, Justice L.B. de Silva, and Justice Sri Skanda Rajah comprehensively examined the concept of “judicial power” and held as follows:

“Judicial power in the sense of the judicial power of the State is vested in the Judicature, i.e. the established civil courts of this country.

|

| Speaker Jagath Wickramaratne |

The Court proceeded to note that:

The Chief Justice and at least one other Judge of the Supreme Court are members of the Judicial Service Commission, a body performing executive functions.”

The Speaker’s ruling does not state why it chose not to follow, or even refer to, that authoritative statement of the Supreme Court.

Speaker Anura Bandaranaike’s ruling

The Speaker’s ruling commences with a reference to what it describes as “a similar ruling” by Speaker Anura Bandaranaike in 2001. The issue in 2001 was fundamentally different. On that occasion, the Supreme Court attempted to prevent a motion for the impeachment of the then Chief Justice from being proceeded with in Parliament. Speaker Bandaranaike very correctly held that the Judiciary had no right to interfere with proceedings in the Legislature. On the other hand, these two institutions of Government do, on occasion, interact. It is the Supreme Court that interprets the laws enacted by Parliament, and it is Parliament that has the power to remove from office a judge of the Supreme Court or the Court of Appeal.

The 1947 and 1977 Constitutions

The Judicial Service Commission (JSC) which the Supreme Court recognised as an executive (and not a judicial) body was initially established by the 1947 Constitution and vested with the power of appointment, transfer, dismissal and disciplinary control of judicial officers and specified public officers employed in courts. The Speaker’s ruling appears to be in error when it suggests that the JSC was “first introduced by the 17th Amendment” to the present Constitution. In fact, it was established (or more accurately, “re-established”) by Article 112 of the Constitution of 1978. That Article restored the JSC consisting of “the Chief Justice who shall be the Chairman, and two Judges of the Supreme Court appointed by the President”, following the repeal of the 1972 Constitution. Article 55 of the 1978 Constitution stated that “The appointment, transfer, dismissal and disciplinary control of judicial officers is hereby vested in the Judicial Service Commission”.

The 1972 Constitution

The 1972 Constitution which created the Republic of Sri Lanka, in a significant departure from the 1947 Constitution, replaced the JSC with a Judicial Services Advisory Board (JSAB) and a Judicial Services Disciplinary Board (JSDB). The Cabinet was the designated appointing authority of district judges and magistrates, and while the JSDB shared the power of removal of a judicial officer with the National State Assembly, its exercise of that power was required to be reported immediately to the Cabinet of Ministers. While serving as Secretary to the Ministry of Justice, I was appointed a member of the JSAB and served on that body for five years. So did the Attorney-General. Neither of us belonged to the Judiciary; nor were either of us entitled to exercise “judicial power”.

The committee stage debate

The motion submitted by 31 Members of Parliament requesting the appointment of a Select Committee to inquire into the exercise by the JSC of its powers conferred by the Constitution appears to have been the immediate consequence of the stormy committee stage debate on the finance allocation for the JSC in the 2026 Budget. The fact that the salaries of the Judges of the Supreme Court are charged on the Consolidated Fund (and therefore not subject to debate or parliamentary vote), but that when three of the judges serve as members of the JSC, their conduct in that capacity can be impugned on the floor of the House, as did actually happen, is sufficient indication that the JSC is not exercising “judicial power”. Nor is the Council of Legal Education exercising “judicial power” merely because it is chaired by the Chief Justice and includes among its members the judges of the Supreme Court.

The Bangalore Principles of Judicial Conduct

The proposed Select Committee, which the Speaker declined to appoint, intended to examine, inter alia, the exercise by the JSC of its power of disciplinary control, including the dismissal, of judicial officers, and make recommendations for improvement. In that connection, I wish to make two observations. The first is that Sri Lanka is today one of the very few countries in the world that has failed or neglected to adopt or apply the Bangalore Principles of Judicial Conduct, the gold standard mandated by the United Nations General Assembly over twenty years ago. That document, which was examined and approved by Chief Justices of both common law and civil law jurisdictions, as well as by the Judges of the International Court of Justice, identifies and defines the six fundamental judicial values, namely, Independence, Impartiality, Integrity, Propriety, Equality, and Competence and Diligence, and proceeds, in a 175-page Commentary, to set out and explain in detail the manner in which judges are expected to conform to them. In the absence of this standard-setting instrument, what is the criteria adopted in Sri Lanka to determine whether a judge or judicial officer is keeping faith with the judicial oath?

Measures for the Effective Implementation of the Bangalore Principles, also endorsed by the United Nations, contains procedures for the disciplining of judges, as well as for the removal of judges from office. Are these procedures being followed by the JSC? These are questions which the proposed Select Committee alone could have explored.

The Istanbul Declaration on Transparency in the Judicial Process

Another relevant instrument is the Istanbul Declaration on Transparency in the Judicial Process. It was initially examined at a conference of chief justices of the Asian-Pacific region, then at a conference of chief justices of the Balkan region, before being finally adopted in 2017 at a conference of chief justices from North and South America, the Caribbean, Europe, Asia and the Pacific, It too was endorsed by the United Nations General Assembly. That instrument describes, inter alia, how the relevant authority should respond to complaints of unethical conduct of judges, as well as the disciplinary process of judges. The proposed Select Committee could have inquired into and reported on whether the JSC acts in conformity with these international standards?

Conclusion

It is unfortunate that the Speaker’s ruling, which cites with approval a 1748 statement of Montesquieu and Erskine May’s 1815 thesis on British parliamentary procedure, failed to explain why it rejected our own Supreme Court’s recognition of the Judicial Service Commission as an executive and not a judicial body. It is also unfortunate that the ruling has denied Parliament the opportunity to inquire into and report on practices and procedures relating to appointments, promotions, transfers, dismissals and disciplinary control of judicial officers currently followed by the Judicial Service Commission, and to recommend how, and the urgency with which, such practices and procedures should be updated to conform to contemporary international standards.

(The author is an academic and a former permanent secretary to the Ministry of Justice.)