Thursday Mar 12, 2026

Thursday Mar 12, 2026

Monday, 29 December 2025 02:36 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The problem is not the disaster itself—Sri Lanka is a tropical island; floods are inevitable. The problem is our financial response. For 75 years, our strategy has been reactive. A disaster strikes, the Budget is derailed, we appeal for foreign aid and development projects are halted to divert funds to relief. This "begging bowl" approach is unsustainable for a middle-income nation attempting to recover from debt default

The problem is not the disaster itself—Sri Lanka is a tropical island; floods are inevitable. The problem is our financial response. For 75 years, our strategy has been reactive. A disaster strikes, the Budget is derailed, we appeal for foreign aid and development projects are halted to divert funds to relief. This "begging bowl" approach is unsustainable for a middle-income nation attempting to recover from debt default

As the floodwaters recede and the health authorities scramble to contain the re-emergence of vector-borne diseases in early 2025, a familiar narrative is unfolding. The new administration, fresh off a historic mandate in late 2024, finds its ambitious economic agenda hijacked by a natural calamity.

As the floodwaters recede and the health authorities scramble to contain the re-emergence of vector-borne diseases in early 2025, a familiar narrative is unfolding. The new administration, fresh off a historic mandate in late 2024, finds its ambitious economic agenda hijacked by a natural calamity.

To the casual observer, this is just bad luck. To the data analyst, however, it is a statistical certainty.

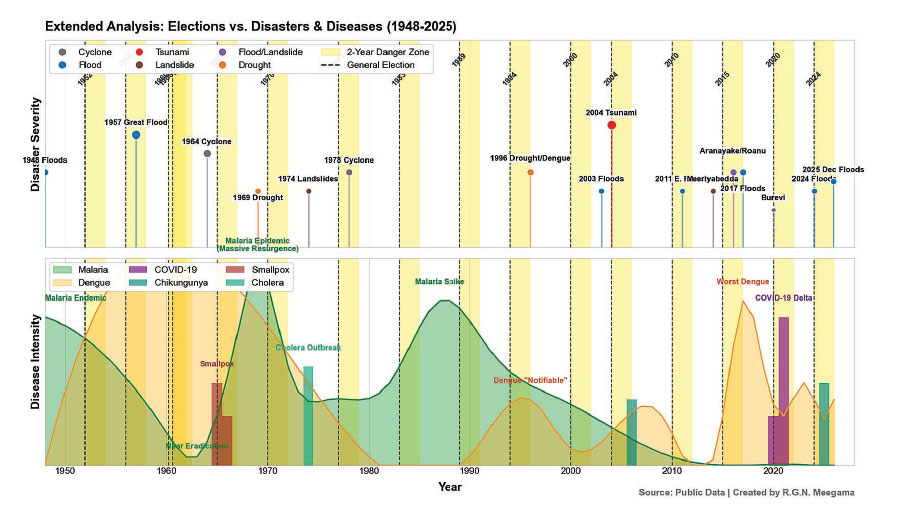

An analysis of Sri Lanka’s political and environmental history over the last 75 years reveals a startling correlation: almost every major change of Government has been met with a significant natural disaster or public health crisis approximately within its first 12 to 36 months in power.

I call this the “Governance Hazard Window.” While natural disasters are unpredictable, their historical alignment with Government formation periods underscores the need for mechanisms that ensure fiscal resilience regardless of political cycles.

The Historical Cycle: A Timeline of Crises: When we visualize the data from 1947 to 2025 (see info-graphic), the pattern is too consistent to ignore. It suggests that the “honeymoon period” for any Sri Lankan Government is a myth; it is, in reality, a countdown to crisis.

following a major spike.

We cannot stop elections and we cannot stop the monsoon. But we can change the financial instrument we use to deal with them. The data argues strongly that Sri Lanka needs to implement a National Disaster Insurance Scheme or a Sovereign Risk Transfer (SRT) mechanism. If one such mechanism existed previously, it should be re-activated immediately. Instead of keeping this liability on the Government’s Balance Sheet, we must transfer the risk to global reinsurance markets

We cannot stop elections and we cannot stop the monsoon. But we can change the financial instrument we use to deal with them. The data argues strongly that Sri Lanka needs to implement a National Disaster Insurance Scheme or a Sovereign Risk Transfer (SRT) mechanism. If one such mechanism existed previously, it should be re-activated immediately. Instead of keeping this liability on the Government’s Balance Sheet, we must transfer the risk to global reinsurance markets

Why does this happen? While it is tempting to look for supernatural explanations, the “Governance Hazard Window” likely stems from a collision of nature and administrative transition. New Governments are often distracted. In the first 24 months, ministries are reshuffled, officials are transferred, and institutional memory is lost. Public health surveillance (such as mosquito control) often dips during these transitions. When a weather event strikes during this period of administrative “reset,” the impact is magnified and the response is a challenging task.

The economic implication: Reactive vs. proactive

The problem is not the disaster itself—Sri Lanka is a tropical island; floods are inevitable. The problem is our financial response. For 75 years, our strategy has been reactive. A disaster strikes, the Budget is derailed, we appeal for foreign aid and development projects are halted to divert funds to relief. This “begging bowl” approach is unsustainable for a middle-income nation attempting to recover from debt default.

A new Government’s economic manifesto is usually the first casualty of this cycle. The fiscal space they planned to use for development is instantly consumed by disaster recovery.

The solution: Sovereign Risk Transfer

We cannot stop elections and we cannot stop the monsoon. But we can change the financial instrument we use to deal with them. The data argues strongly that Sri Lanka needs to implement a National Disaster Insurance Scheme or a Sovereign Risk Transfer (SRT) mechanism. If one such mechanism existed previously, it should be re-activated immediately.

Instead of keeping this liability on the Government’s Balance Sheet, we must transfer the risk to global reinsurance markets. Instruments like Parametric Insurance—which pays out automatically when rainfall or wind speeds exceed a certain threshold—could provide immediate liquidity within days of a crisis, bypassing the months of bureaucratic assessment that currently delay relief.

The timeline from 1948 to 2025 is a wake-up call. The risk of a major crisis hitting a new Government is not an anomaly; it is a systemic feature of our political cycle. It is time to move beyond superstition and start treating this risk with the seriousness of a financial liability. Rather than hoping for the best, we have the opportunity to use data-driven decision-making to proactively secure our economy against climate risks.

(The author is Senior Professor in Computer Science, Department of Computer Science, Faculty of Applied Sciences, University of Sri Jayewardenepura)