Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Friday, 2 May 2025 00:30 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Any new constitution under President Disanayake must address the fundamental flaws of the current devolution system established by the 13th Amendment

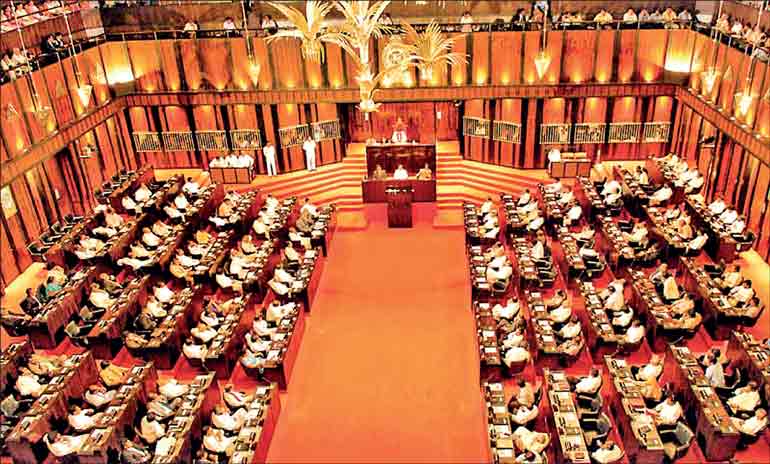

Sri Lanka’s recently elected President, Anura Kumara Disanayake’s political coalition—the National People’s Power (NPP), won an overwhelming amount of support from the majority Sinhalese community as well as the minority Tamil community, receiving a historic supermajority in the November 2024 Parliamentary elections. This broad mandate across ethnic lines presents a historic opportunity to address the constitutional deficiencies that have plagued the nation since independence, particularly the challenges of ethnic conflict and democratic governance. As the country seeks to rebuild after its devastating economic crisis, the lessons from the past attempts at constitutional reform offer crucial insights for crafting meaningful solutions.

Sri Lanka’s recently elected President, Anura Kumara Disanayake’s political coalition—the National People’s Power (NPP), won an overwhelming amount of support from the majority Sinhalese community as well as the minority Tamil community, receiving a historic supermajority in the November 2024 Parliamentary elections. This broad mandate across ethnic lines presents a historic opportunity to address the constitutional deficiencies that have plagued the nation since independence, particularly the challenges of ethnic conflict and democratic governance. As the country seeks to rebuild after its devastating economic crisis, the lessons from the past attempts at constitutional reform offer crucial insights for crafting meaningful solutions.

On 3 August 1995, Sri Lanka’s then-President Chandrika Kumaratunga put forward a constitutional reform proposal known as the “Union of Regions” proposal. To date, it remains the boldest attempt to constitutionally redress the grievances of the minority communities of the nation. Unfortunately, due to political rivalry among the two major Sinhala political parties, and the refusal of the Tamil-separatist rebel group, the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), to engage with the proposals, the constitutional initiative was ultimately torpedoed.

This article argues that President Disanayake’s new constitution for Sri Lanka should incorporate many of the features that were present within the proposals put forward by the Kumaratunga government. The 3 August proposals, developed with significant input from Harvard Law educated constitutional scholar Dr. Neelan Tiruchelvam, offered a comprehensive framework for power-sharing that could address the root causes of Sri Lanka’s ethnic conflict while maintaining the country’s territorial integrity.

The urgency of constitutional reform has been underscored by Sri Lanka’s recent economic and political crisis. According to a 2024 survey on Democracy and Reconciliation by the Centre for Policy Alternatives (CPA), three-quarters of Sri Lankans believe that democracy is preferable to any other forms of government, while a majority (52.3%) preferred a new constitution—a figure that has increased considerably from 2016 to 2024. The public’s demand for constitutional reform was dramatically amplified during the 2022 Aragalaya protests, when citizens demonstrated their willingness to directly challenge and oust President Gotabaya Rajapaksa who had violated a social contract through authoritarian and corrupt governance that led to national bankruptcy.

President Anura Kumara Disanayake campaigned on a platform of constitutional reform, vowing to “abolish the Executive Presidency” and replace it with a president “without executive powers” appointed by Parliament. He pledged to introduce a new constitution aimed at “strengthening democracy and ensuring equality of all citizens,” building on the reform process initiated in 2015, which he notes remains “incomplete.” Crucially, he promised that the proposed changes would guarantee “equality and democracy” through the “devolution of political and administrative power to every local government, district, and province,” allowing all citizens to participate in governance “within one country.” He also committed to creating “a new parliamentary electoral system,” tackling another deeply rooted concern in Sri Lanka’s governance.

The Executive Presidency: A failed experiment

The presidential system introduced by Sri Lankan President J.R. Jayewardene in 1978 has repeatedly failed to fulfil its promises of political stability, economic growth, and lasting peace. As Sri Lankan academic Jayadeva Uyangoda noted, Jayewardene “undermined Sri Lankan parliamentary democracy” by establishing what he himself referred to as an “executive presidential system” through the 1978 constitutional reforms. This shift had far-reaching consequences: the presidency became “the sole centre of power,” while Parliament was effectively subordinated to the president’s office.

The presidential system introduced by Sri Lankan President J.R. Jayewardene in 1978 has repeatedly failed to fulfil its promises of political stability, economic growth, and lasting peace. As Sri Lankan academic Jayadeva Uyangoda noted, Jayewardene “undermined Sri Lankan parliamentary democracy” by establishing what he himself referred to as an “executive presidential system” through the 1978 constitutional reforms. This shift had far-reaching consequences: the presidency became “the sole centre of power,” while Parliament was effectively subordinated to the president’s office.

British academic Jonathan Spencer described the Jayewardene era as marked by an “appalling decline,” pointing out that although the political environment in 1977 was far from ideal, the situation deteriorated significantly over the following decade, culminating in insurgency in the South and the presence of foreign troops.

Considering this legacy, President Disanayake should therefore prioritise the long-overdue abolition of the Executive Presidency. The excessive concentration of power in a single office has repeatedly resulted in authoritarianism, corruption, and inconsistent governance. The Gotabaya Rajapaksa presidency starkly demonstrated the dangers of this system, as his unilateral decisions—such as sweeping tax cuts for the rich and a sudden shift in agricultural policy—played a major role in precipitating the country’s economic crisis.

Beyond the unitary state: Reimagining Sri Lanka’s constitutional identity

President Disanayake must address the fundamental conceptual barrier to meaningful power-sharing: the designation of Sri Lanka as a “unitary state.” As constitutional expert Rohan Edrisinha explained, this term was introduced in the 1972 Republican Constitution by Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandranaike as “a direct slap in the face of the Tamil people” who had been advocating for federalism within a united Ceylon. The term “unitary” in Sri Lankan politics carries heavy symbolic weight that extends beyond legal terminology. As Edrisinha noted, “there’s a lot of emotion, there’s a lot of ignorance and there’s a lot of misunderstanding about this term.” The conflation of “unitary” (akeya) with “united” (exa) in Sinhala has led many to wrongly believe that abandoning a unitary structure means fragmenting the country.

As highlighted by author Partha Sarathy Ghosh, the August 3rd proposals sought to divide the island into eight autonomous regions, fundamentally transforming Sri Lanka’s constitutional character. Instead of being defined as a unitary state, Sri Lanka would be recognised as a “union of regions” where regions would be “fully autonomous both in terms of executive and legislative powers.” This represented a profound shift in the constitutional authority, as “Article 76 of the Constitution which gives absolute power of legislation in the country to the Parliament is to be abrogated as the same power is now to be shared by the Regional Councils as well.”

This linguistic and conceptual shift was far more than semantic; it represented a fundamental reconceptualisation of the Sri Lankan state that acknowledged the country’s pluralistic character while providing constitutional safeguards for its territorial integrity. As former Constitutional Affairs Minister, G.L. Peiris, who was one of the formulators of the 3 August proposals observed, previous proposals were often characterised by “insincerity” where “on the surface, you appear to concede various things but then you incorporate into the proposal certain devices, certain techniques by recourse to which you are able to take back what you have professedly given.” The 3 August proposals sought to break this pattern by offering genuine devolution without hidden mechanisms or recentralisation.

Paikiasothy Saravanamuttu, founder of the Centre for Policy Alternatives in Colombo, emphasised the significance of this change: the 1995 proposals represented “a major departure, qualitative departure, from this obsession with the unitary state.” By removing the unitary designation, the proposals sought to create space for genuine power-sharing without threatening the country’s territorial integrity. Journalist Jehan Perera observed that the Sri Lankan government, drawing inspiration from India’s model of a “union of regions” rather than a unitary state, incorporated this concept into its constitutional proposals–crediting Neelan Tiruchelvam as the key figure who inspired this shift.

President Disanayake should follow this lead and move beyond the restrictive unitary model, perhaps by adopting the “union of regions” concept or a similar formulation that acknowledges both unity and diversity. This would be consistent with his campaign promise to ensure “that all people can be involved in governance within one country.”

Current limitations of the 13th Amendment: The need for meaningful devolution

Any new constitution under President Disanayake must address the fundamental flaws of the current devolution system established by the 13th Amendment. As Rohan Edrisinha observed, the central issue lies in “the three lists” that define the powers of the National and Provincial Parliament, along with a concurrent list. The imbalance arises because the list for the central government is “comprehensive, all-embracing, sweeping,” while the provincial list is “extremely narrow,” leaving little meaningful space for regional autonomy.

Sri Lankan academic Jayadeva Uyangoda further pointed out that although there are “three lists”—one for the central government, one for provincial councils, and a concurrent list—in reality, “the concurrent powers” have consistently remained under the control of the central government. He also emphasised that Sri Lanka’s judiciary lacked the institutional development seen in India’s judicial system and was therefore unable to rule in favour of provincial councils when disputes over the division of powers arose.

The fundamental problem with the 13th Amendment is that whatever powers the central government gave to the regions with one hand, could, in effect, be taken away with the other hand. The 3 3rd proposals addressed this by abolishing the concurrent list contained in the 13th Amendment. By removing the concurrent list, the proposals made powers between the centre and the region more defined and distinct, and implemented checks that made it more difficult for the central government to unilaterally usurp powers given to the regions.

The proposals, with the removal of the concurrent list, advocated that “the respective powers of the Centre and the regions are contained in the Reserved List and the Regional List, respectively. To ensure that the centre does not meddle in the affairs of the region, [the proposals] clearly provided that the Chief Ministers cannot be removed from office so long as they enjoy the confidence of the Regional Councils. The Governors are not supposed to be the watchdogs of the Central interests as is the case in India and their appointment by the President will be strictly with the concurrence of the Chief Ministers. To resolve disputes between the Centre and the Regions or between and among the regions, there will be a permanent commission on devolution appointed by the Constitutional Council. The Commission would have powers of mediation as well as adjudication.”

Essentially powers to devolve: Drawing from the 3 August proposals

President Disanayake’s constitution for Sri Lanka should draw inspiration from the 3 August proposals. Several specific powers must be meaningfully devolved to the regions in President

Disanayake’s constitution.

Land powers were a central concern of the August 3rd proposals. As former Sri Lankan Constitutional Affairs advisor, Jayampathy Wickramaratne noted, the proposals included powers over “agriculture’ and “irrigation,” both of which are fundamentally connected to land use and management. Control over land use, administration, and development within their territories is vital for minority communities concerned about demographic changes through state-sponsored settlement schemes.

Police powers represent another contentious but essential area for devolution. As Wickramaratne explained, the 1995 proposals included provisions for “some of the law-and-order powers, leaving some to the centre,” recognising the need to balance local control with national security concerns. This balanced approach would allow regions to address local security concerns while preserving the centre’s role in national security. Furthermore, a level of regional autonomy with respect to police powers is desperately needed as presently many Tamils in the North complain about the lack of police officers in the region who speak Tamil, even though more than 93% of the province consists of Tamil speakers. In 2019, the Senior Deputy Inspector General of Police, Roshan Fernando, said that only 12% of the province’s 6,000 police force speaks Tamil.

Financial autonomy was a key innovation of the 3 August proposals. Dr. Tiruchelvam had identified the “extreme dependence of the province on the centre with regard to financing” as a critical flaw of the Thirteenth Amendment.

The 3 August proposals addressed this by giving regional councils the power to borrow as well as set up their own financial institutions. Additionally, the proposals advocated for “a National Finance Commission entrusted with the job of allocating grants to the regions keeping in view balanced regional development.” The 1995 proposals recognised that meaningful autonomy is impossible without fiscal independence.

Education represents another vital area for devolution, with regions needing authority to shape educational systems that reflect their linguistic and cultural characteristics. As Wickramaratne noted, the Kumaratunga government’s proposals included provisions for “provincial education, provincial universities,” recognising the importance of educational autonomy in preserving and promoting regional linguistic and cultural identities.

To be continued.

(The author is a writer and filmmaker. He holds a Master of Global Affairs degree from the University of Toronto’s Munk School of Global Affairs. Pitasanna has co-created a critically insightful documentary series on Canadian foreign policy titled “Truth to the Powerless: An Investigation into Canada’s Foreign Policy.”)