Saturday Feb 07, 2026

Saturday Feb 07, 2026

Monday, 2 October 2023 00:11 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The International Monetary Fund last week released the first ever Governance Diagnostic Assessment on Sri Lanka as part of its technical assistance initiative. Here is the executive summary of the 139-page report which can be accessed via online https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2023/09/29/Sri-Lanka-Technical-Assistance-Report-Governance-Diagnostic-Assessment-539804

At the request of the authorities of Sri Lanka, an inter-departmental (LEG/FAD/MCM, FIN) Governance Diagnostic Assessment (GDA) mission was conducted during 20 to 31 March 2023. In line with the IMF’s 2018 Framework on Enhanced Fund Engagement on Governance,1 the diagnostic assessment focused on corruption vulnerabilities and governance weaknesses linked to corruption in macro economically critical priority areas of: (i) the anti-corruption, anti-money laundering and combating the financing of terrorism; (ii) fiscal governance (e.g., public financial management, tax policy and revenue administration, state enterprise management, and public procurement); (iii) central bank governance; (iv) financial sector oversight; and (v) enforcement of contract and protection of property rights. Annex 1 provides additional information on the methodology and scope of the Governance Diagnostic.

Sri Lanka is an island nation that lies in the Indian Ocean off the coast of India and that is highly connected to the global market. The economy has begun the transformation from primarily agriculture to higher value added industry and service sectors and has the potential to further diversify and upgrade its economic structure. As of now, the Sri Lankan economy relies primarily on tourism, tea export, clothing, rice, and other agricultural production.

In recent years, a confluence of shocks and policy missteps led to a deep economic and governance crisis. Two years of low tourism revenues due to COVID, loss of market access, deep reductions in tax revenues, and the debt service burden depleted reserves. The economic downturn was further exacerbated by a series of policy choices, many of which generated gains for private individuals while saddling the nation with debts. The country defaulted and FX shortages led to nationwide power cuts, shortages of essentials, and long queues for petrol. The rupee depreciated by about 40% (in dollar terms) between February and March 2022. Inflation soared and the economy contracted sharply while the banking sector was put under extreme stress by a state-granted

moratorium of domestic debt repayment. The poverty level nearly doubled from its pre-pandemic level to about 25.6% of the population living below the USD 3.65 poverty line. Popular protests against Government policies and widespread corruption, starting in March 2022, spotlighted the role of a small number of connected individuals who wielded enormous power and authority. President Rajapaksa resigned in July 2022, and Ranil Wickremesinghe assumed the Presidency later that month.

President Wickremesinghe has set out a reform program designed to stabilise the economy and country featuring a combination of steps to restore fiscal and debt sustainability, improve governance, and reduce corruption risks. The program includes measures to cut spending, raise revenues, and restructure debts, while maintaining necessary social programs to meet severe social needs. A raft of governance changes is also envisioned, including steps to strengthen the independence of the central bank, and enhance the country’s ability to confront corruption and integrity issues. The IMF approved an Extended Fund Facility (EFF) Arrangement with Sri Lanka in March 2023 to support the implementation of reforms required to address critical balance of payment issues.

Sri Lanka continues to face severe economic, social and governance challenges. Despite tentative signs of macroeconomic stabilisation with inflation moderating, exchange rate stabilising, and the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL) rebuilding reserves buffers, social tensions remain high due to falling real incomes. Government measures to address the balance of payment crisis, including tax reforms and cost-recovery pricing in the energy sector, have raised the cost of living while continued shortages of essentials, strong-arm measures against protestors, and the postponement of local Government elections have been sources of popular discontent. Large fiscal deficit and elevated debt continued to weigh on the recovery prospects. The absence of visible progress on addressing corruption and holding officials to account for past behaviour raises popular concerns that officials will continue to enjoy impunity for their misconduct.

In this context, the authorities have requested IMF assistance to analyse governance weaknesses and corruption vulnerabilities that are macro-critical in their own right and stand in the way of achieving the objectives of the reform program. The recommendations provided are designed to align laws, institutions, and incentives towards more effective public sector performance and better outcomes. In keeping with the IMF’s Framework for Enhanced Governance Engagement, efforts to address governance weaknesses and corruption vulnerabilities in Sri Lanka are approached as complements and essential to sustained progress on fiscal consolidation and inclusive social and economic growth. Analysis and recommendations exclusively concern the areas established in the 2018 Framework and do not capture governance concerns that are beyond these parameters.2 The report is based on information gathered before and during March 2023, and does not capture

reforms introduced since March. The publication of the Governance Diagnostic by the end of September 2023 is a structural benchmark in the Fund’s program.

The GDA revealed systematic and severe governance weaknesses and corruption vulnerabilities across state functions, with particular macroeconomic impact in: budget credibility; expenditure control; public investment management and control of spending); public procurement; management and oversight of State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs); transparency of revenue policy and the integrity of revenue administration; the governance and legal frameworks of the Central Bank; the application of financial sector regulations; and clarity and security of land ownership and the integrity of the judicial sector. Corruption vulnerabilities are exacerbated by weak accountability institutions, including the Commission to Investigate Allegations of Bribery and Corruption (CIABOC) that have neither the authority nor competency to successfully fulfil their functions.

Current governance arrangements have not established clear standards for permissible official behaviour, acted to deter and sanction transgressions, nor pursued individuals and stolen public funds that have exited the country. Regular civil society participation in oversight and monitoring of Government actions is restricted by limited transparency, the lack of platforms for inclusive and participatory governance, and by broad application of counter-terrorism rules.

These weaknesses and vulnerabilities highlight several broader governance themes that need to be addressed for planned reforms to be sustained. Problematic structural issues that shape governance dynamics include the compromised independence of key governance institutions, critical gaps in the legal and regulatory infrastructure for managing and overseeing public resources, limited fiscal discipline and transparency, and a disorganised regulatory and legislative process that provides for insufficient review and engagement. Minimal progress has been made in integrating modern information technology into public sector operations and public private interfaces, or in linking information to detect and correct inefficiencies and improprieties. These governance features form the basis for the substitution of informal mechanisms of control for rule-based system of accountability for performance and integrity over an expansive state. The impunity for misbehaviour enjoyed by officials undermines trust in the public sector and compounds concerns over limited access to efficient and rule-based adjudication process for resolving disputes.

Specific weaknesses in each area can be summarised as the following:

Current practices by financial institutions largely fail to identify suspicious transaction and prevent money laundering. At the same time, weaknesses in the legal framework, problems in domestic cooperation on corruption related issues between competent authorities, and issues in establishing effective protocols for collaboration with foreign jurisdictions impair sanctioning corrupt officials for money laundering offenses or recovering stolen assets.

findings and observations contributes to the persistence of problematic procedural and managerial practices while restricting accountability for past actions.

Concerns about the use of Government authority relating to tax policy highlight limited Government attention to protecting competition, including the lack of a competition policy agency on the one hand and extensive Government control of markets in critical sectors, including agriculture and construction materials.

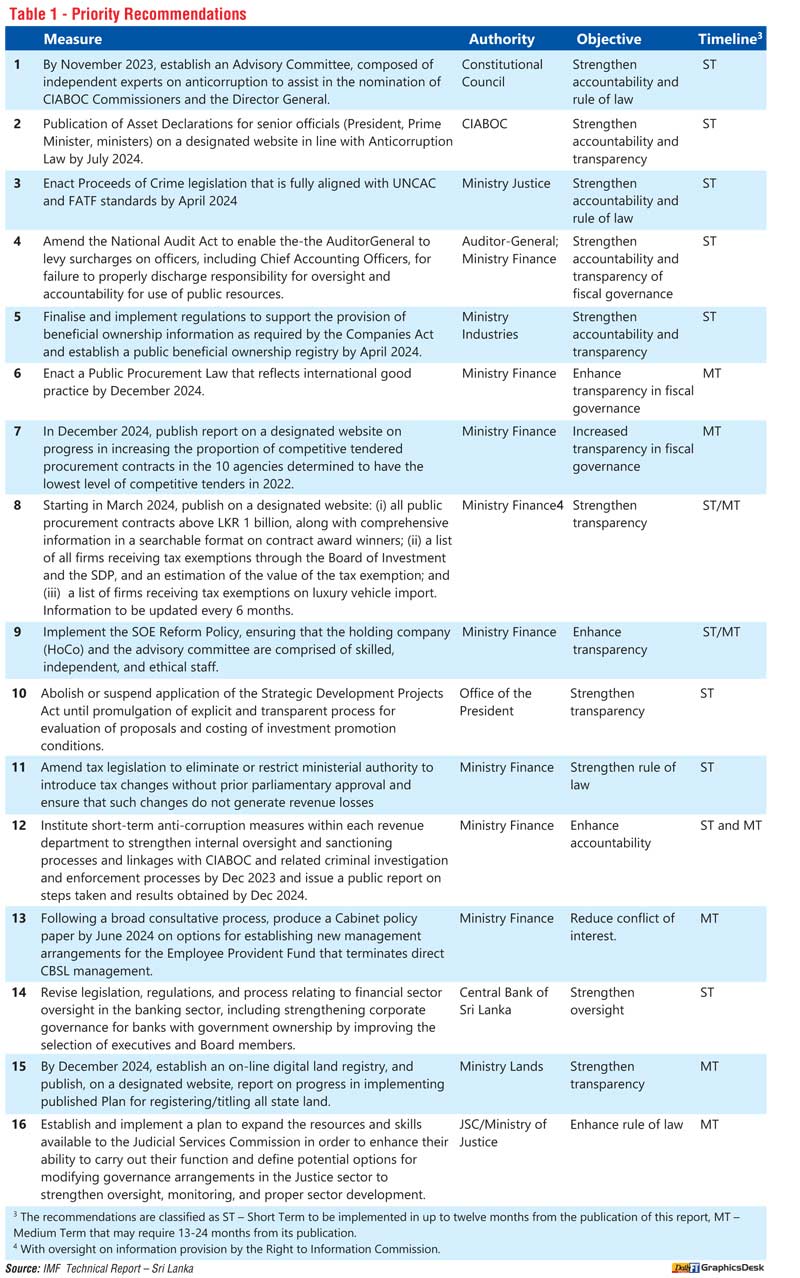

The report highlights immediate and short-term measures to address key corruption issues, as well as structural reforms that require more time and resources but are essential to strengthen governance and initiate lasting change. A list of “priority” recommendations is provided below. They primarily focus on measures related to critical risks, including addressing gaps in existing legal frameworks and the public provision of essential information for oversight and monitoring. Priority recommendations are explored in more depth in the subsections of the report, which also contain more extensive recommendations, including structural and institutional measures to achieve more transparent and efficient governance that operates with integrity and in accordance with the rule of law.

The recommendations are designed as a coherent approach to improving governance through a focus on: clarity of authority and responsibility for core functions; financial and operational independence of essential accountability and law enforcement institutions; transparency in Government practices and performance, especially relating to the planning, spending, and accounting for the use of public funds and assets; inclusive, accessible, and rule-based means to enforce private agreements and challenge official behaviour; and efficient mechanisms for making information public and holding organisations and individuals to account for their performance and behaviour. The combination of short-term actions to deliver concrete and observable improvements and long-term structural initiatives to change how the public sector functions in Sri Lanka is essential to achieving the social and economic aspirations of the country.

It is acknowledged that comprehensively addressing governance weaknesses would require medium – and long-term initiatives, significant resources, and prolonged efforts, including with support from Sri Lanka’s international partners. The recommendations coming out of this diagnostic will contribute to the formulation of governance and anticorruption policies and programs, improvement of the legal and institutional frameworks, as well as governance and anti-corruption reform measures agreed to in the Staff Level Agreement for an Extended Credit Facility Arrangement for Sri Lanka.

Footnote

2 A large variety of governance diagnostics exist, reflecting different analytical frameworks and concerns. For example, the World Bank’s Systematic Country Diagnostics provide an assessment of the constraints and drivers of progress towards the twin goals of ending poverty and boosting

shared economic prosperity. The Bertelsmann Transformative Index measures the development status and governance of political and economic transformation processes. The Ibrahim Index of African Governance is a biennial survey-based assessment of the quality of governance relating to

the provision of political, social, economic, and environmental goods that a citizen has the right to expect from the state. For Sri Lanka, the recently published “Civil Society Governance Diagnostic Report” provides an alternative governance perspective.