Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Thursday, 6 November 2025 05:04 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

South Centre Executive Director Dr. Carlos Maria Correa

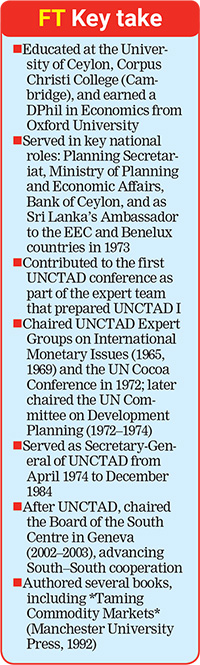

Dr. Gamani Corea

– Pic by Upul Abayasekera

By Devan Daniel

Sri Lanka and the wider Global South should decide where the value is added in their supply chains, push for credible technology transfer, and demand a fairer financial architecture, South Centre Executive Director Dr. Carlos Maria Correa said in the Dr. Gamani Corea 100th Birth Anniversary Oration.

Sri Lanka and the wider Global South should decide where the value is added in their supply chains, push for credible technology transfer, and demand a fairer financial architecture, South Centre Executive Director Dr. Carlos Maria Correa said in the Dr. Gamani Corea 100th Birth Anniversary Oration.

He tied those priorities to Corea’s record at UNCTAD and his role in building Southern coalitions, saying the economic weight of developing countries makes the agenda timely.

“The real fight is where the value is added,” Carlos said, urging commodity producers to process minerals and raw goods domestically to capture jobs, fiscal revenue and scale.

He cited Indonesia’s export restrictions on unprocessed minerals as a policy that forces investment into upstream processing. Developing countries now account for about 46% of global GDP and more than 25% of global R&D spending, he said, figures that give leverage if they coordinate positions and pool capabilities.

“The scenario is changing and there is hope, particularly if there is South–South cooperation.”

Carlos linked today’s economic bottlenecks to the agenda Corea drove at UNCTAD from the mid-1970s.

He recalled the integrated program for commodities proposed in 1976 to reduce price volatility, producer–consumer agreements on coffee, cocoa, sugar, tea, timber and rubber, and the Common Fund for Commodities created in 1980, which still finances stabilisation and value-addition projects.

Corea had also treated debt distress as a systemic issue, pressed for collective solutions, and opened the way for the first non-official multilateral restructurings. On market power, Carlos cited UN principles on restrictive business practices that shaped the first generation of competition laws across developing countries.

The oration revisited the 1974 UN General Assembly declaration on a New International Economic Order, which Gamani Corea helped translate into a work program.

Carlos said its principles, policy space to choose development models, sovereignty over natural resources, preferential treatment for developing nations, and oversight of transnational corporations, remain unresolved.

He noted that UNCTAD’s attempt to create a code on technology transfer ultimately failed, and that the same imbalance continues under modern intellectual property regimes.

“We have not reached what Corea was aiming at in terms of increasing transfer of technology,” Carlos said, criticising vaccine makers’ refusal to share technology during the pandemic and calling for mandatory sharing mechanisms in health and other sectors.

Carlos added that Corea’s focus on sustainability and equity predated modern development thinking.

Corea’s question, he said, was not just how fast an economy grows, but whether growth is environmentally responsible and fairly distributed.

“That thinking, anchors a human-centred model that values wellbeing, resilience, and the role of the State alongside markets and civil society. It also explains Corea’s insistence on collective action.

“The Group of 77, which he helped found and draft into being, remains the main platform for developing countries to prepare, negotiate and hold lines together. Individually or alone, they cannot influence outcomes of international negotiations. They need to act together,” Carlos said.

He tied that lineage to current trends. Manufacturing capacity is now concentrated in the South, advanced economies are re-shoring to capture more value at home, and several developing nations are banning raw ore exports to encourage local processing.

Carlos said these shifts vindicate Corea’s push for value addition at source and indigenous technological capability.

He urged reform of creditor governance to reflect debtor interests, faster technology-sharing mechanisms, and deliberate expansion of South–South trade, investment and knowledge networks.

Carlos shared a personal reflection.

“Within weeks of his assuming office, it became clear that he was going to wield significant influence on the development of international economic affairs,” he quoted from a contemporary account.

“Corea advocated international cooperation, but cooperation that would lead to a more just world order,” he said. “He shaped UNCTAD’s agenda, catalysed the G77, and stands as an intellectual tower whose legacy guides the South to add value at home, build its own technological strength, and negotiate as one.”

“He was a statesman. He was a diplomat. He was an intellectual. He was a real leader of the Global South. The goal of his life was to find ways to support and improve the conditions of the Global South.

“He advocated for international cooperation, for South–South cooperation, and for justice, not law as such, but cooperation that leads to a more just world order. Gamani Corea is a true symbol of intellectual leadership and moral courage,” Carlos said.

A centenary paper released by the South Centre on 4 November expands on Dr. Gamani Corea’s institutional legacy.

It traces his influence before UNCTAD, his role in 1965 talks that led to the IMF’s Special Drawing Rights, chairing of the 1972 UN Cocoa Conference, participation in the 1969 tea agreement, and his contribution to the 1972 Stockholm process that led to the UN Environment Program. It also notes UNCTAD’s rebranding as UN Trade and Development.

The paper characterises 1974–84 as “Corea’s decade,” citing outcomes that turned ideas into institutions: the Integrated Program for Commodities (later called the Corea Plan), the Common Fund for Commodities (agreed in 1980, operational in 1989), and the Global System of Trade Preferences among Developing Countries.

These reflected the New International Economic Order’s logic of structural reform and collective action. It connects this legacy to UNCTAD-16 in October 2025, which called for a more responsive and inclusive UN trade and development body.

The paper also recalls Corea’s 1978 initiative at UNCTAD that secured more than $ 6 billion in official debt relief, an early form of collective restructuring that shaped later frameworks like HIPC. It draws a direct line to the present, noting that global public debt now exceeds $ 100 trillion and warning that the Seville FfD4 outcome only opened discussions on fixing the debt architecture, without delivering real reform.

The institutional thread continues through Corea’s leadership in the G77 and the South Centre. He drafted the G77’s first declaration at UNCTAD I, pressed for unity on mechanisms as well as objectives, and later chaired the South Centre’s Board.

The Geneva-based Gamani Corea Forum, launched in 2014, continues to train G77 delegates in multilateral negotiations.

The special issue also republishes Corea’s 1984 warning that global recession, militarisation, and political fractures were eroding multilateralism, a warning it says still applies.

Its prescription mirrors Carlos’s oration: developing countries should use Southern platforms to coordinate positions, push for creditor-governance reform, enforce technology-sharing frameworks, and harness shifting value chains to move into higher-value production at home.