Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Tuesday, 18 November 2025 00:41 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

For Sri Lanka’s rural communities, the impact has been just as severe. The ban is estimated to have cut off approximately Rs. 2.5 billion in annual income that flowed into these communities from the plantation industry. But the more profound tragedy is the lost future for smallholder farmers. The policy has blocked their only viable path to integrating into the world’s most efficient oil crop sector. While neighbouring countries like India are actively supporting new smallholders with subsidies for fertiliser and planting materials, Sri Lanka’s farmers are left with no such opportunity

For Sri Lanka’s rural communities, the impact has been just as severe. The ban is estimated to have cut off approximately Rs. 2.5 billion in annual income that flowed into these communities from the plantation industry. But the more profound tragedy is the lost future for smallholder farmers. The policy has blocked their only viable path to integrating into the world’s most efficient oil crop sector. While neighbouring countries like India are actively supporting new smallholders with subsidies for fertiliser and planting materials, Sri Lanka’s farmers are left with no such opportunity

The strange and sudden ban on palm oil

The strange and sudden ban on palm oil

In April 2021, we received news that the Sri Lankan Government had banned palm oil imports and ordered the uprooting of oil palm trees to be replaced with rubber trees (Gazette No. 2222/13). The main reason given was palm oil’s negative social and environmental impacts, based on a disputed 2018 report. Interestingly, it wasn’t an outright ban on all palm oil. The policy had a critical, and damaging, loophole: it specifically prevented the import of crude palm oil, the raw ingredient used by Sri Lankan factories. At the same time, it explicitly allowed the import of refined, finished palm oil. The ban caused price increases for essential products such as cooking oil, margarine, confectionery, and other consumer goods that rely on palm oil as a key ingredient. These higher costs were passed on to consumers.

The economic effect

The ban didn’t stop palm oil from entering the country; it only stopped local companies from processing it. The policy effectively paralysed the nation’s domestic refining industry, which was built on processing that low cost, raw feedstock. The import data proves this shift. In 2023, Sri Lanka still imported $23 million worth of palm oil (down from $28 million in 2022). But tellingly, 99% of this was the expensive, refined product, confirming the move from raw materials to finished goods.

With local refiners starved of crude palm oil, the country had to find a substitute, and the financial shock was massive. Imports of coconut and palm kernel oils skyrocketed, jumping from just 24% of the total oil import bill in 2022 to a staggering 65% in 2023. But again, this was not raw material. In 2023, these imports were dominated by $99 million in finished, refined coconut oil, compared to just $16.9 million in its crude form.

This created a “Coconut Oil Deficit Trap.” If the ban was meant to help the local coconut industry, it ignored a simple fact: Sri Lanka doesn’t produce enough. The nation needs about 240,000 tons of coconut oil a year, but local farms produce only 40,000 tons which is just 16.7% of demand. The ban simply forced the country to import the massive 200,000-ton shortfall. But instead of importing cheap crude palm oil, Sri Lanka was now importing finished coconut oil at a premium estimated at a staggering $1,500 per tonne. This results in exchange rate losses of around US$15-20 million per month, or $150-200 million per year. This single policy choice inflicted a massive and avoidable drain on the nation’s foreign currency reserves.

A nutrition squeeze: Availability fell as prices rose

A nutrition squeeze: Availability fell as prices rose

Analysis of official data from the Department of Census and Statistics (DCS) and other market sources reveals that the ban has created a significant challenge for nutrition security. DCS data for 2013-2017 showed a total fat supply of 52 g/day, or 18.98 kg/person/year. “Vegetable oils” were the single largest contributor at 32%, implying a historical vegetable oil availability of approximately 6.0 kg/person/year. However, the per capita availability of vegetable oil fell to 3.5 kg in Sri Lanka in 2022. As per World Health Organisation (WHO), it is essential to have 25–30 g of visible fats and oils per adult per day for a 2,000-kcal diet (visible fats include cooking oil, ghee and butter). Thirty grams per day works out to ~10.95 kg per person per year. For comparison, Indonesia’s per capita consumption of vegetable oil in 2022 was estimated to be 29.16 kg/capita/year. Even neighbouring India’s per capita consumption of vegetable oil in 2022 was approximately 19.7 kg per year, according to a report by NITI Aayog. If the 3.5 kg figure is accurate, it signifies a catastrophic failure of food security. It would mean the ban led to price inflation (substituting cheap crude for oil at a $1,500/ton premium ), which has pushed a staple food item out of reach for millions, triggering a collapse in caloric intake from fats.

The ban didn’t stop palm oil from entering the country; it only stopped local companies from processing it. The policy effectively paralysed the nation’s domestic refining industry, which was built on processing that low cost, raw feedstock. The import data proves this shift

The ban didn’t stop palm oil from entering the country; it only stopped local companies from processing it. The policy effectively paralysed the nation’s domestic refining industry, which was built on processing that low cost, raw feedstock. The import data proves this shift

A lost opportunity for self-sufficiency in vegetable oils

The 2021 ban on oil palm cultivation and crude oil imports did not just disrupt a market; it pulled the rug out from under an entire domestic industry, creating a crisis for established plantation companies and eliminating a future path to prosperity for rural smallholders. For the large-scale Regional Plantation Companies (RPCs), the policy was an existential blow. These companies had invested over Rs. 23 billion (approx. $75 million) in nurseries, processing facilities, and research, often to diversify away from loss-making crops like rubber. The ban left these assets instantly underutilised, forcing the abandonment of saplings worth more than Rs. 550 million and halting all expansion. 1 More than 5,000 direct jobs were lost.

The Government then dealt a second blow. While blocking the crude oil feedstock, it slapped an 18% VAT and a 2.5% Social Security Levy on any locally refined oils. This “one-two punch” made it financially impossible for domestic refiners to compete with the very finished oils that were still being allowed into the country.

For Sri Lanka’s rural communities, the impact has been just as severe. The ban is estimated to have cut off approximately Rs. 2.5 billion in annual income that flowed into these communities from the plantation industry.

But the more profound tragedy is the lost future for smallholder farmers. The policy has blocked their only viable path to integrating into the world›s most efficient oil crop sector. While neighbouring countries like India are actively supporting new smallholders with subsidies for fertiliser and planting materials, Sri Lanka›s farmers are left with no such opportunity.

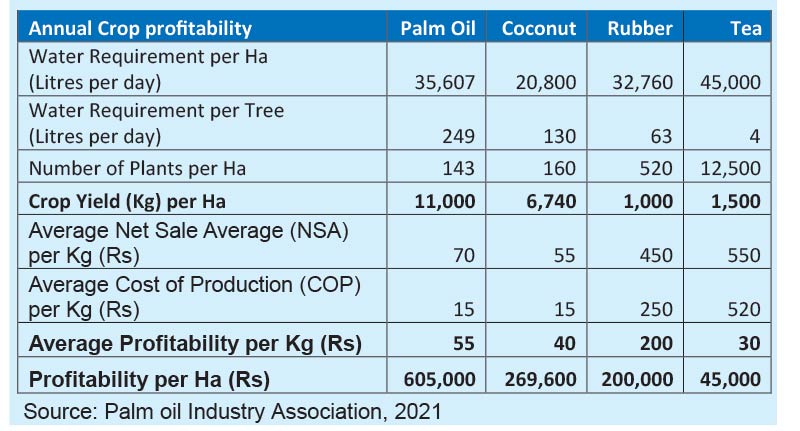

In Southeast Asia, numerous studies showed that oil palm cultivation contributes to income gains, capital accumulation, and higher expenditures on food, health, education, and durable consumer goods in smallholder farm households (Alwarritzi et al. 2016). In Africa, farm households are generally better off cultivating oil palm than when they do not. A study in Ghana showed that oil palm farmers have higher incomes and suffer less from multidimensional poverty than other farmers after controlling for possible confounding factors (Ahmed et al. 2019). When we compare the competing commodities in Sri Lanka, interesting results can be observed. From the table, we can see that the profitability of palm oil per hectare is SLR 605,000, compared to SLR 269,600 for coconut, SLR 200,000 for rubber, and SLR 45,000 for tea. It means that while using much less land and almost the same water level, oil palm can provide a much better financial return to a farmer.

The benefits of oil palm production in Sri Lanka extend beyond farm households to positively impact the community. In Sri Lanka, according to the Household Income and Expenditure survey (2016), an oil palm worker earned about Rs. 40,000 more annually than a household involved in rubber cultivation, and Rs. 75,000 more than a household involved in tea cultivation. Palm oil emerges as a crop with higher income benefits for plantation workers.

The 2030 ticking time bomb: Sri Lanka's growing oil deficit

As Sri Lanka battles its way back to economic stability, its self-inflicted edible oil crisis is set to become a massive, structural drain on the nation’s finances for the next decade. The numbers paint a grim picture of a completely avoidable foreign exchange catastrophe.

Currently, Sri Lanka’s annual edible oil requirement is approximately 264,000 tons. Driven by population growth and rising incomes, this demand is projected to soar. With per-capita consumption forecast to grow at over 3% annually, Sri Lanka could see its national demand climb to over 343,000 tons by 2030.

The problem is that domestic production is nowhere near catching up. Even optimistic projections show local edible oil production reaching only 91,000 tons by 2028.

This leaves a staggering import deficit of over 252,000 tons per year by 2030.

If the current ban remains, Sri Lanka will be forced to import this entire deficit at high cost, as finished oil. This policy choice would lock in an avoidable foreign exchange loss of over $375 million every single year—a figure that dwarfs the already-crippling $150-200 million in annual losses the policy is causing today. For a nation operating under the strict fiscal discipline of an IMF program, deliberately choosing the most expensive import path threatens to undermine its long-term economic recovery.

Is palm oil unsustainable?

In the global conversation on environmental health, palm oil has become public enemy number one. But the data suggests that palm oil is not the villain; it is, quite simply, the most efficient and resource-miserly vegetable oil on the planet.

The central, unavoidable fact is land use. Research published by MDPI categorises oil crops into two groups: “land-friendly” and “land-hungry”. Oil palm is in a class of its own. It is a marvel of efficiency, producing an average of 3.3 tons of oil per hectare. Now, compare that to its “land-hungry” competitors. Soybean yields are just 0.5 tons per hectare. Sunflower yields 0.8 tons, and rapeseed 0.7 tons. This is not a small difference; it is a mathematical chasm. To get the same amount of oil that one hectare of palm produces, you would need to plant 6.6 hectares of soy or 4.1 hectares of sunflower. In the Sri Lankan context, this efficiency is staggering. To meet the nation’s annual vegetable oil demand, it would require an estimated 271,000 hectares of coconut groves. To get that same amount of oil from oil palm, it would require only 50,000 hectares.

This is precisely why major conservation bodies like the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), Solidaridad Network and the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) have warned against boycotts. They argue, based on this data, that banning palm oil would not save forests. It would simply displace global oil demand onto crops that require 5 to 8 times as much land, dramatically accelerating global deforestation.

The environmental benefits go beyond land. A global study on water footprints found that producing one ton of coconut oil requires 10,548 cubic meters of water. Producing one ton of palm oil requires just 3,946 cubic meters—less than 40% of the water. The efficiency extends to nutrients. To produce the same amount of oil, a coconut tree requires about 17.2 kg of fertiliser. An oil palm tree needs only 6 kg and, when replacing other plantations, shows “no conclusive evidence” of harming biodiversity more than those crops.

In Sri Lanka, it’s also a myth that oil palm replaced pristine forests; it has overwhelmingly replaced other, less profitable plantation crops, mainly rubber. Tellingly, comparative studies on biodiversity between oil palm,

rubber, and tea plantations in Sri Lanka found the differences were “neither significant nor conclusive”. In fact, one study found that leaf litter faunal density was highest in oil palm and lowest in tea. Far from degrading the land, studies on the ground in Sri Lanka found “no evidence of soil and water resource degradation” in well-managed estates.

Debunking the health myths: Palm Oil as a source of nutrition, not just a scapegoat

Palm oil’s reputation has been so thoroughly tarnished by organised campaigns that its nutritional value is rarely part of the public conversation. Yet, under scientific scrutiny, many health myths crumble, revealing an oil that is not only superior to its tropical peers in key safety aspects but also a vital tool for global nutritional security.

The most common attack centres on saturated fat. Critics correctly state that palm oil is about 50% saturated fat. But this fact is almost always presented in a vacuum, ignoring two critical contexts. First, its primary competitor, coconut oil—often marketed as a “health food” is nearly 90% saturated fat. Second, the other 50% of palm oil is a balanced profile of “good” fats, including about 40% monounsaturated fat (the same kind lauded in olive oil) and 10% polyunsaturated fat. Coconut oil contains almost no beneficial monounsaturated fat (about 6%).

But the case for palm oil isn’t just about what it lacks; it’s about what it provides. Unrefined Red Palm Oil is a nutritional powerhouse and a critical, food-based solution to global malnutrition. It is one of the richest natural sources of pro-Vitamin A carotenoids on the planet, containing approximately 15 times more retinol equivalents than carrots and 300 times more than tomatoes.

This makes it an indispensable tool for combating Vitamin A Deficiency (VAD), a leading cause of preventable childhood blindness in developing nations. Clinical studies in both India and Africa have confirmed that supplementing diets with red palm oil is “highly efficacious” in improving the Vitamin A status of at-risk children and women. It has even been shown to increase the provitamin A content in the breastmilk of nursing mothers, directly enhancing the nutritional security of infants.

Finally, palm oil is one of the world’s richest natural sources of tocotrienols, a unique and highly potent form of Vitamin E that is rare in other foods. Emerging research suggests these compounds have powerful neuroprotective properties, helping to protect brain function, as well as potential anti-cancer effects.

In the global conversation on environmental health, palm oil has become public enemy number one. But the data suggests that palm oil is not the villain; it is, quite simply, the most efficient and resource-miserly vegetable oil on the planet

In the global conversation on environmental health, palm oil has become public enemy number one. But the data suggests that palm oil is not the villain; it is, quite simply, the most efficient and resource-miserly vegetable oil on the planet

The way forward: Four actions Sri Lanka can take now

1) Replace the blanket cultivation ban with a regulated licensing regime: The 2021 decisions combined a cultivation phase-out (Gazette No. 2222/13) with import licensing that effectively blocked crude palm oil (Gazette No. 2222/31). This choked domestic refining and shifted the country to costlier finished oils. Replace the ban with permits tied to strict siting, water rules and independent audits.

2) Launch a time-bound National Oil Palm Mission focused on smallholders and mills:

Establish a time-bound National Oil Palm Mission centred on smallholders and mills. The programme would aim to deliver 300,000 tons within the next eight to ten years, with acreage capped and pre-zoned for suitability. During the three to four years before first harvest, provide concessional finance for nurseries, irrigation and intercropping, and support cluster mills so that fresh fruit bunches are processed within 24 hours, preserving quality and farm-gate prices. At typical global yields of 3.3 to 3.5 tons per hectare, this output implies about 86,000 to 91,000 hectares, subject to rigorous site selection and water safeguards. Two non-negotiables must apply. There should be no conversion of natural forest; new plantings should only replace existing plantations or genuinely degraded land, verified through independent HCV/HCS assessments. Water use should be governed by transparent caps, with monitoring at the estate level. The Sri Lanka Palm Oil Association can draw technical support from MPOB in Malaysia, DMSI in Indonesia and IIOPR in India, while the Government explores concessional finance with the Asian Development Bank.

3) Adopt a national sustainability standard aligned to trade reality: The world’s biggest producers, like Indonesia and Malaysia, have decided to create their national sustainability frameworks called Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO) and Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil (MSPO), respectively. India has developed its national sustainability framework in the form of the Indian Palm Oil Sustainability (IPOS) framework. A Sri Lanka Sustainable Palm Oil (SSPO) standard certified by external auditors will ensure social and environmental compliance.

4) Fix the tax and tariff signals so we import raw material, add value at home, and keep retail prices low: It is essential to review how the existing taxes interact with customs duties so local refiners are not penalised against finished oil imports. It will be a great help to reinstate a crude-vs-refined duty differential that favours domestic refining and jobs, subject to strict quality and trans-fat enforcement.

Conclusion

Sri Lanka can keep paying a premium for finished oils while its refineries sit idle, or it can reopen a rules-bound path for crude feedstock and smallholder-led oil palm that cuts prices, saves forex and protects people and nature. With clear licences, fast FFB-to-mill logistics, an SSPO standard aligned to regional practice, and a tax regime that rewards value addition at home, the country can restore affordable, safe edible oils without lowering environmental or labour standards. That is the pragmatic choice.

The author is a sustainability analyst and writer specialising in agroecological transitions in Asia. He is the Managing Director of Solidaridad Asia and a member of its Global Executive Board. An economist by training, his expertise spans sustainability strategy, climate finance, and inclusive value chains. He can be reached via email at [email protected].