Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Friday, 18 July 2025 00:22 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Sri Lanka’s narrow, under-developed export base is the key constraint on both debt sustainability and long-term growth

Temu and Trump tariffs reveal the same underlying issue: decades of strategic neglect of trade, investment and industrial policy by successive Sri Lankan Governments. The US recently imposed a 30% tariff on Sri Lankan exports, down from the 44% announced in March but still a significant threat to our export sector.

Temu and Trump tariffs reveal the same underlying issue: decades of strategic neglect of trade, investment and industrial policy by successive Sri Lankan Governments. The US recently imposed a 30% tariff on Sri Lankan exports, down from the 44% announced in March but still a significant threat to our export sector.

At the same time, local manufacturers are being undercut by ultra-cheap imports through platforms like Temu and AliExpress, which exploit an informal, per-kilogram customs clearance method according to Sanjay Samarasinghe of Aramex, who stated that this process was likely causing customs revenue losses of Rs. 35–50 million daily. P. Yasotharan of the Sri Lanka Brands Association describes the practice as “dumping,” contributing to SME closures in garment hubs. The Government is moving to replace weight-based duties with itemised rates, but this response highlights a deeper problem: Sri Lanka lacks a coherent trade reform agenda, industrial strategy, and structural transformation plan. While countries like Vietnam and Malaysia integrated into global value chains through strategic state support, Sri Lanka remains stuck in a reactive, protectionist model.

In an 11 July statement, the Joint Apparel Association Forum (JAAF) warned the 30% tariff “threatens to erode competitiveness,” noting that Vietnam had secured a 20% rate and Bangladesh, despite a 35% rate, is negotiating reductions. “We risk seeing a migration of US buyers,” JAAF cautioned. Sri Lanka has offered no reciprocal reforms such as reducing para-tariffs or easing non-tariff barriers. This reflects a broader failure: protectionism and tax holidays have long sheltered inefficiency without building competitive industries.

Unlike successful Asian economies that used protectionism selectively with sunset clauses and clear deliverables, Sri Lanka’s approach has been disorganised and ad hoc; the 2025 National Tariff Policy remains only partially implemented; core elements of a modern industrial strategy are absent. There is no major investment in export infrastructure, no incentivisation of industry towards electronics and technology components, pharmaceuticals, or other advanced manufacturing; supply chains are fragmented, R&D is negligible and no roadmap exists for joining global production networks.

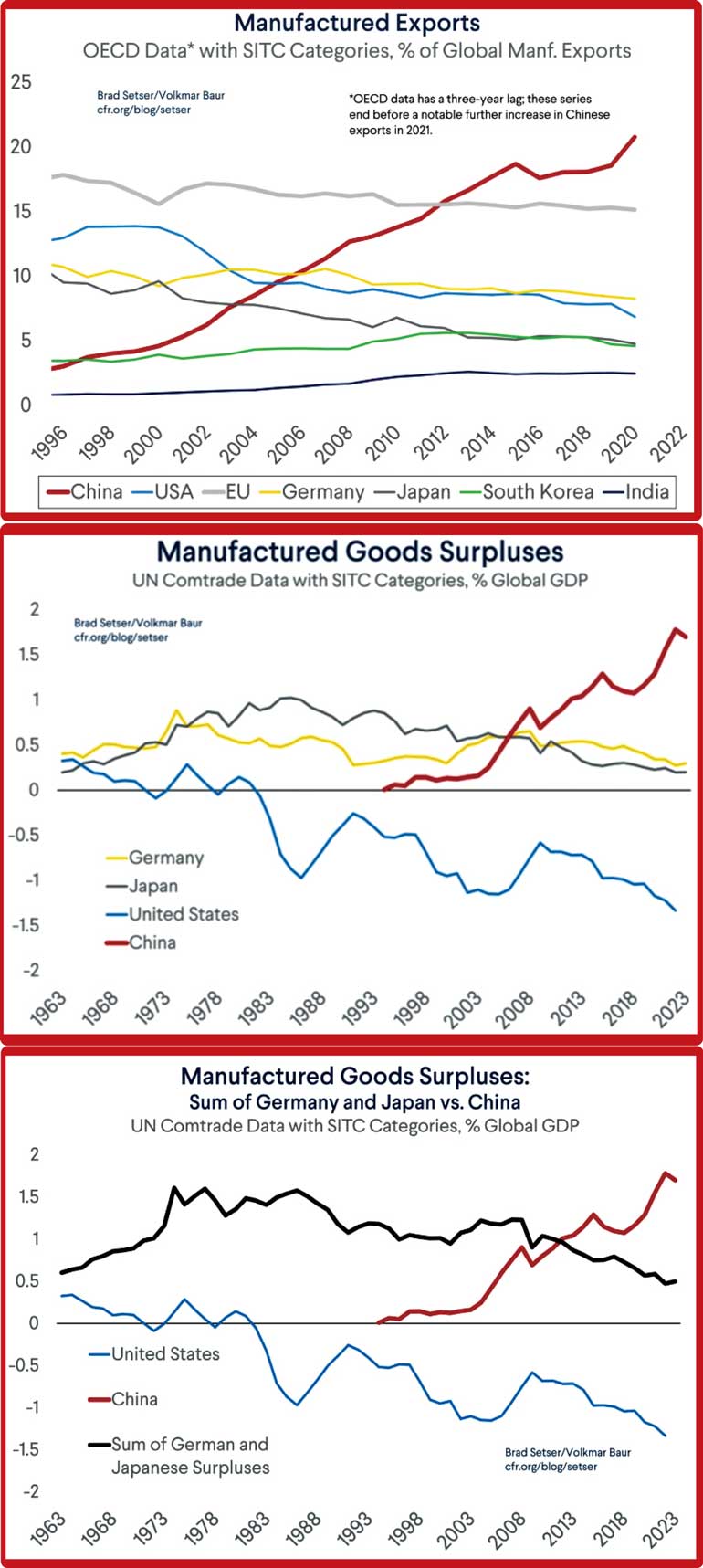

The uproar over Temu is more than a customs issue, just like the Trump tariffs are more than a trade issue; both underscore how unprepared Sri Lanka is for the modern global economy. Even in the US, Temu’s abuse of the “de minimis” rule is facing scrutiny, becoming a major election campaign topic during the 2024 cycle. Economists like Brad Setser warn of China’s overwhelming industrial scale; in a March 2024 article, Sester, Senior Visiting Fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, together with Michael Weilandt and Volkmar Baur of Union Investment, state that China’s “dominance of global manufacturing trade” should not be understated, while “Shifts in China’s bilateral trade data with the US are sometimes considered evidence that China’s centrality to global manufacturing supply has fallen… in fact, China’s post-pandemic surplus in manufacturing, which has now reached about 2% of world GDP; far exceeds the peak surpluses run by export powerhouses like Japan and Germany”. The charts illustrate the growth and dominance of Chinese manufacturing exports.

For Sri Lanka, generating competitive industries in advanced technology sectors without targeted industrial policy, is wishful thinking. Ultimately, the problem is not protectionism per se, but its indiscriminate use. Sri Lanka lacks a transparent framework to determine which sectors deserve support, which should be exposed to competition, and how trade policy should align with long-term industrial development.

The bond trap

Sri Lanka’s external sector is central not only to economic development but also to debt sustainability. Real net dollar inflows will ultimately determine the viability of the country’s growing external debt stock. Under the IMF program, Sri Lanka’s trajectory remains vulnerable: by 2027, external debt-to-GDP could reach 60%, with external debt making up half of total public debt. About 40% of this is expected to be in International Sovereign Bonds (ISBs), returning to peak 2016 levels and exposing the country to rollover risk, currency mismatches, and global interest rate shocks.

The IMF requires the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL) to build gross official reserves to $ 15–16 billion by 2028. As of May 2025, reserves stood at around $ 6 billion but this figure includes a RMB 10 billion ($ 1.4 billion) currency swap with the People’s Bank of China, which FactCheck.lk notes is non-compliant with IMF criteria. Per IMF guidelines, “only assets that are readily available and free from conditions can be classified as reserve assets.”, the Chinese swap is not considered usable, placing true reserves closer to $ 5 billion as per IMF guidelines.

A return to capital markets is a core IMF objective. Once access is restored, Sri Lanka is expected to issue up to $ 1 billion annually in ISBs, with proceeds likely added to reserves, a common practice among emerging markets. Yet this strategy is fraught with risk; former IMF Chief Economist Ken Rogoff warns the era of cheap credit is over, with global interest rates stabilising around 4 or 5%, making refinancing far more expensive, particularly for countries like Sri Lanka with weak fiscal buffers and low institutional credibility. In a June 2025 Washington Post article, Rogoff linked investor fatigue in sovereign bonds, even US Treasuries, to the broader fragility of foreign-currency borrowing, which he describes as the “original sin.”

The IMF itself has described Sri Lanka’s debt trajectory as “on a knife edge,” where even modest shocks could derail progress. Meanwhile, the program’s fiscal consolidation plan aims for a 2.3% primary surplus by 2027, to be maintained for three years. Without corresponding growth in exports or productivity, higher taxes will depress consumption, worsen affordability, and undermine public support; threatening both economic recovery and reform momentum.

The missing strategy

While officials speak of market diversification, what’s urgently needed is product diversification. Sri Lanka’s narrow, under-developed export base is the key constraint on both debt sustainability and long-term growth. Sustaining current consumption and import levels without repeated borrowings demand a fundamental shift toward high-value, high-tech exports. In contrast to successful Asian peers like South Korea, Singapore, and Vietnam, who used deliberate industrial policy, strong institutions, and public-private collaboration to build globally competitive sectors, Sri Lanka lacks any coherent strategy for developing its exports. The Board of Investment (BOI) functions more as a promotional body than a serious facilitator, while education remains misaligned with industry needs, and industrial zones suffer from poor connectivity, weak logistics, and policy inconsistency.

Industrial development has historically relied on protectionism, subsidies, tax incentives, and technology transfers. Every advanced economy, from the US, UK, and Japan to Singapore, Taiwan, and South Korea, either maintains or once built, a high-technology industrial manufacturing base. These countries succeeded by shielding strategic sectors while investing in capacity and innovation. Strategic protectionism remains relevant today, with the US under both Presidents Biden and Trump, and the European Union, actively pursuing industrial policies to re-shore manufacturing and secure supply chains.

Sri Lanka, under its current IMF program, has no fiscal space for large-scale industrial subsidies and lacks the industrial base to justify classical protectionism. Beyond apparel, which still accounts for over 40% of merchandise exports, and a small cluster of automotive component firms, Sri Lanka remains largely excluded from global production networks.

In New Structural Economics (World Bank 2013), Justin Lin argues that governments should back firms with export potential through infrastructure, incentives, and pilot support: “Drawing on comparative advantage, self‑discovery, and the facilitating state … the government … should encourage the experimentation, and scale‑up efforts of private enterprises by removing constraints, supporting pilots, and providing direct incentives to pioneer firms.” In this framework, FDI into tradable sectors like electronics and components can serve as a discovery mechanism to help domestic firms enter global value chains.

Deputy Minister Chaturanga Abeysinghe recently announced efforts to expand electrical component exports through a partnership between Sri Lanka’s ME Group and China’s Dvolt Electric Ltd targeting the US and EU markets.

However, FDI alone is insufficient. In a 2004 Harvard working paper, Dani Rodrik cautioned that spillovers from FDI are not automatic: “The task of industrial policy is as much about eliciting information from the private sector on significant externalities and their remedies as it is about implementing appropriate policies.” Without active state coordination, FDI may not deliver long-term development benefits. Sri Lanka currently has no significant presence in high-tech manufacturing, no semiconductor or electronics assembly base, and no integration into the higher tiers of global value chains. The country lacks the institutional ecosystem, technical education, industrial R&D, export finance, etc. required to support competitive manufacturing. In such a context, it seems the only viable path to industrial upgrading lies in attracting strategic FDI that brings capital, technology, managerial know-how, and access to global markets.

An Industrial Revolution, televised

There is a growing trend among developing countries, particularly small, open economies like Sri Lanka, to pursue service-led development, emphasising tourism, IT-enabled services, finance, and logistics. This vision, often framed in terms of modernity and integration into the global knowledge economy, is flawed if it overlooks a fundamental historical reality: no country has achieved and sustained high-income status without first undergoing a significant phase of export-oriented industrialisation.

Even economies commonly cited as service-driven success stories, such as Singapore and Hong Kong, either emerged from or remain anchored in strong industrial foundations. Singapore, while celebrated for its finance and logistics sectors, maintains one of the most advanced manufacturing bases in the world. It is a global hub for biomedical production, aerospace engineering, and semiconductors, with industry contributing significantly to GDP and exports. As economist Ha-Joon Chang has argued, the so-called “post-industrial” economies are better understood as “hyper-industrial”, they have not abandoned manufacturing but evolved it into high-tech, capital-intensive sectors, often invisible to casual observers yet central to their resilience.

Sri Lanka, by contrast, is attempting to leapfrog into services without experiencing an industrial takeoff. This is both historically atypical and economically dangerous. In his 2015 paper “Premature Deindustrialisation”, Dani Rodrik warns that many developing nations are reaching peak industrial employment and output at much lower income levels than past industrialisers. This limits their ability to absorb labour, benefit from productivity convergence, and drive structural transformation. Rodrik emphasises that manufacturing is “special” for growth, it is tradable, productivity-enhancing, and subject to technological diffusion. Services, by contrast, are often non-tradable, fragmented, and exhibit wide disparities in productivity.

East Asian success stories underscore this trajectory. South Korea did not become a high-income country by pivoting to services, but through decades of industrial policy, export competitiveness, and technological upgrading, progressing from textiles to steel, shipbuilding, automobiles, and ultimately semiconductors. Today, manufacturing still accounts for nearly 30% of Korean GDP, and even sectors like K-beauty, are rooted in industrial sophistication and state support.

China followed a similar path. From less than 10% of GDP in manufacturing in the 1980s, it rose to over 30% by the early 2000s, establishing itself as the world’s factory. Only after securing global dominance in industrial exports has it begun to pivot toward high-tech services like AI and digital finance.

Empirical evidence from UNIDO and the World Bank confirms that sustained industrial expansion is a prerequisite for successful service-sector growth. In virtually all high-income countries, services became dominant only after a long period of rising manufacturing output and exports. This sequencing is critical: high-value services such as R&D, fintech, and advanced logistics thrive only in economies with the industrial capacity, human capital, and infrastructure to support them.

Sri Lanka’s current exposure to shocks: from the Trump tariffs on exports, to the flood of cheap imports from platforms like Temu, reveals an economic structure unprepared for international competition. The country’s industries, labour force, and institutions remain overprotected and underdeveloped, ill-equipped for the demands of a fast-changing global economy. Without deliberate, export-oriented industrialisation, Sri Lanka risks deepening its vulnerabilities rather than overcoming them.

(The writer has 15 years of experience in the Financial and Corporate sectors after completing a Degree in Accounting and Finance at the University of Kent (UK). He also holds a Masters in International Relations from the University of Colombo. He is a media presenter, political commentator and Foreign Affairs analyst, invited regularly on television broadcasts as a resource-person. He is also a member of the Working Committee of the Samagi Jana Balawegaya (SJB).)