Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Thursday, 11 May 2023 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

A peaceful society cannot exist until there is racial equality, or at least a genuine attempt to address the central issues. I still maintain that war crimes charges on both sides are needed for reconciliation to happen. No matter if you are a Sinhalese or a Tamil, there is a basic universal truth: we always have more in common than different across all races, religions, and political ideologies. Instead of deepening your past divisions, you need to strengthen your present bonds

By Shanika Sriyananda

|

Roy adorning the tie his father gave as a parting gift at the Colombo airport 35 years ago on 18 April 1988. According to Roy, he never wore it until 35 years later on 18 April 2023

|

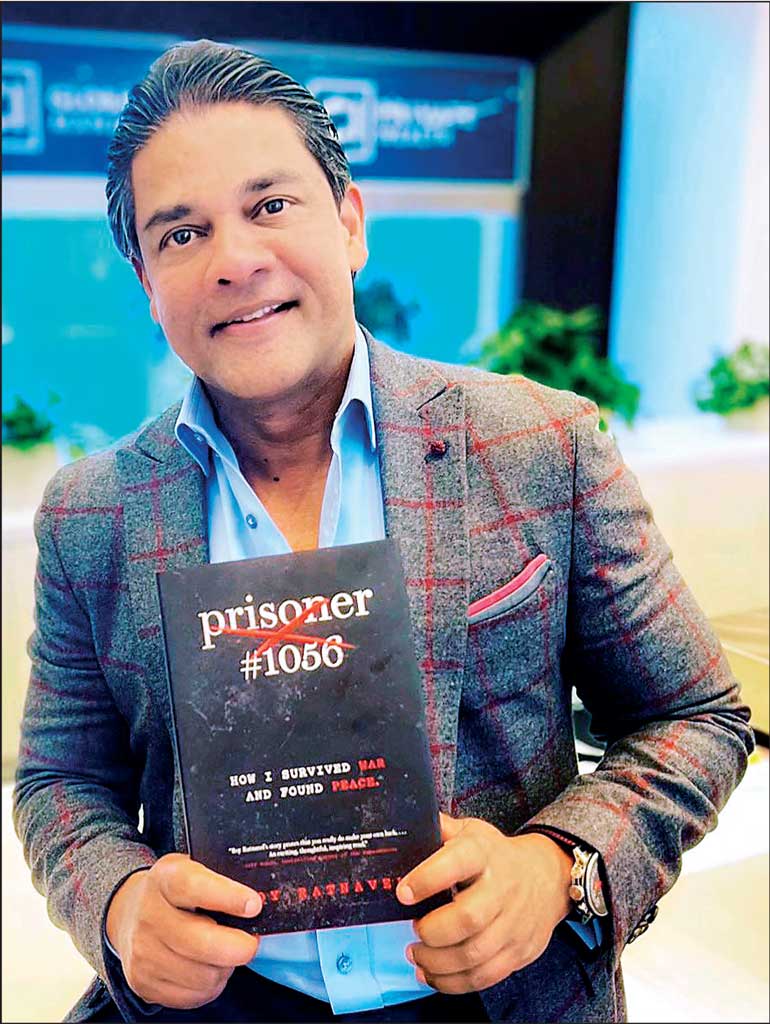

Roy Subendran Ratnavel, a Sri Lankan born Canadian recounts in his memoir ‘Prisoner #1056’ – How I survived war and found peace – released recently about his journey of fleeing the war-torn Sri Lanka in 1988 at the age of 18 years after being released from the Boosa Prison with only $ 50 in hand, starting the new life at a Bay Street investment firm sorting mails and later reaching as one of the top financial executives of the CI Financial Corp., which is the largest independent investment company in Canada. He was selected as one of Canada's 50 Best Executives in 2020.

“Ultimately I realised that revenge was not the solution to whatever. The best way to avenge is to live better and to fulfil the very reason that my father sent me to Canada,” Ratnavel, who says he was tortured and humiliated at the prison, said.

He believes although past events are unchangeable, they can serve as important lessons in overcoming struggles in life to strive for a better future.

“When we are no longer able to change a situation, we are challenged to change ourselves,” he said in an interview with the Daily Financial Times, in which he recalled his past as a prisoner, Canada’s desire to promote ethnic harmony, politics in Sri Lanka and diasporas’ contribution to rebuild Sri Lanka.

“The secrets in my success story are to be likeable, learn from those who have done it, and work hard,” says Ratnavel, whose memoir, which is also a ‘thank you gift to his Appa (father)’, has topped the Canadian Non-Fiction list, today.

Following are the excerpts of the interview:

Q: Can you recall the journey of the terrified teenager, who fled his own motherland hopelessly with only $ 50 in hand?

When I was released at the age of 17 after being tortured by Sri Lankan officials in prison, my father realised that there is no bright future for a young Tamil boy like me in Sri Lanka and decided to send me away, and thought Canada might be that land of opportunity. And he was right in his assessment. While I do not remember everything I felt when I left Sri Lanka, I do remember thinking that I needed to start a whole new life, make new friends, and adapt to a new language and culture.

Q: What was your motive to write the memoir and why did you name it ‘Prisoner #1056’?

In my thirties, perhaps around the age 35 or 36 years, I knew that I would one day write a book. A book about being terrorised as a young boy who experienced a brutal civil war in Sri Lanka and then transformed in Canada in his late teens and early twenties. I wanted to tell the world this survival story – a Tamil boy’s survival story. I chose the title ‘Prisoner #1056’ because it was my prisoner number in the Boossa Prison.

Also, I wanted this book to give voice to a generation of Tamil immigrants who are coming of age now in Canada and other Western nations and tell their untold stories or their parents leaving Sri Lanka and their experiences prior to arriving on friendly shores to build a better future.

Finally, this book is a homage to Canada. This country gave me a second lease on life.

Q: It says the book is dedicated to ‘freedom and democracy’. Why?

Yes, it is dedicated to freedom and democracy because my appreciation for both is boundless. From my teenage experience in Sri Lanka, I know full well that it is far easier to lose my freedom than to attain it. In many parts of the world, people are seeking freedom and democracy, and so I wanted people who live in Western countries to protect this basic human right and not take it for granted. Freedom and democracy are non-negotiable Western values. This is core to my new identity as a Canadian.

Q: As a teenage boy, who says he was tortured and humiliated in the Boossa Prison, how do you describe your healing process?

The crux of it isn’t about revenge. If it was just about revenge then that would be it, correct? You would say my father died at the hands of the IPKF, Rajiv Gandhi was in charge of that, so the score is settled. But there was nothing about my life, at that time, that was settled. I did not have my father, I was a mess, and my mother was battling with mental illness as a result.

The solution was going back to what my father said. “I don’t want you to survive, I want you to live. The determination to persevere and find meaning in life is what ultimately makes you a winner. It is not about revenge. The best way to avenge is to live better and to fulfil the very reason that my father sent me down here.

Though past events are unchangeable, they can serve as important lessons in overcoming struggles in life to strive for a better future. When we are no longer able to change a situation, we are challenged to change ourselves. We are all worthy of the life we desire. But it can only happen under the right conditions. Canada provided me with those conditions. I gained the gift of freedom and safety here. It was a much-needed prosthetic for my amputated soul.

Sometimes if you break down the barriers to see someone as purely human and then that feeling can unite people beyond race and religion and other superficial markers. In fact, that’s the theme running through my book

Q: Your journey, which started in a mailroom, has brought you to one of the top positions in the financial sector in Canada. What was the secret?

The secrets to success are the same now as they were when I started out three decades ago: be likeable, learn from those who have done it, and work hard. There is dignity in hard work. There is no dignity in blaming others. Habits play an important role as you go about your life. They allow you to efficiently complete the most challenging and repetitive tasks that life presents. Being conscious of what you do that is consistent with your goals and being accountable for your daily actions are the keys to creating excellent habits that can increase your odds of success.

Q: Your father had Sinhalese friends in Colombo and you too have Sinhala friends. What do you think caused the ‘conflict’ between the two ethnicities that lived together for centuries?

If those who are currently living in Sri Lanka don’t know what caused this ethnic conflict, then they haven’t been paying attention or are wilfully blind. It was not all Sinhalese who were guilty of committing atrocities. There were many Sinhalese nothing but heroically humane amidst all the hatred and violence. However, it was the Sri Lankan Government elected by the people that is responsible for all what happened in the past. There is no law in life or nature that says a group may commit atrocities against another with impunity, without consequences. Anyone who thinks otherwise needs to reread history books.

Uncle Fernando, a Colonel in the Army, was my father’s friend who rescued me from the prison. He didn’t look at me as an enemy. He looked at me as a friend’s son. There is some beauty in that too, in humanity. Sometimes if you break down the barriers to see someone as purely human and then that feeling can unite people beyond race and religion and other superficial markers. In fact, that’s the theme running through my book.

Q: Don’t you think that politics with different agendas stirred ethnic disharmony in the North and South?

A: No, I do not think that at all. Sri Lanka’s first prime minister enacted discriminatory laws against Tamils that, over time, turned this promising nation into a hell on earth for Tamils. The pain Sri Lanka had to endure was appalling, but it doesn’t make a martyr of Sri Lanka, nor—much as one might like—does it sweep away all arguments about the ambiguities of Sri Lanka’s participation in its own downfall.

Q: These two ethnic communities are living peacefully today. Do you still believe in the separate homeland ideology?

A: It is a misnomer. Just because there isn’t war it doesn’t mean there is peace. If such peace exists currently, then there is no need for the heavy military occupation of the traditional Tamil lands in the North and East. This is a clear indication that Sri Lanka has been and still is governed by leaders who have not learned from the past. It is symptomatic of a country light years away from attaining true nationhood. To that end, the political aspiration of Tamils is still alive and well.

Q: While you were living comfortably, bearing the scars of being an ex-prisoner, thousands of youths who were misled had fought and got wounded badly in the deadly war that ended in 2009. As a member of the Tamil diaspora, what have you done to support the ex-LTTEers, who have reintegrated into society?

Since I arrived in Canada, I have been living in two worlds, one with loss, grief, and endless misery and the other with peace, prosperity, and profit. One was painful and the other, gratifying. But, even if one asserted that the Tamil Tigers were largely to be blamed and were the authors of their own people’s misfortune, the plight of the Tamils and the egregious transgressions of Sri Lanka since the independence in 1948 simply could not be ignored. The ex-LTTE combatants are still citizens of Sri Lanka. So, the Government of Sri Lanka bears the full responsibility of caring for and rehabilitating them. I would argue the Tamil diaspora has done more for them than Sri Lanka can muster up but no question that more can be done by the diaspora to uplift them.

Q: Still, there are thousands of Tamil youth and war widows in the North and East who are struggling to make a living. How do you comment on the Tamil diaspora’s role in supporting them?

Again, it is the responsibility of the Government to care for its citizens. Tamil diaspora will continue to invest in the North and assist with creating sustainable industries, skill developments, access to employment and economic viability for those who were severely impacted by the war.

Q: As an expatriate, how do you comment on the present situation in Sri Lanka?

The democratic political system assumes a certain minimum level of ethical behaviour, responsibility and civility on the part of elected government officials that is above what is explicitly spelled out by the Constitution. If those ethics are absent—well, democracy just isn’t going to work. In the absence of an overwhelming and fundamental change in Sri Lankan attitude and behaviour, equality of race and religion will never be possible. In 1948, when Sri Lanka gained its independence, it was considered to be the postcolonial nation most likely to succeed economically and democratically. Unfortunately, since then, Sri Lanka has been governed by leaders with a penchant for racial division. Through the hatred that they sowed; they have succeeded in destroying the country. It is heart-wrenching to see where Sri Lanka is currently.

Q: The Government has made a clarion call to the Sri Lanka Diaspora to invest in the country in this crucial situation for Sri Lanka’s economy. What is your comment?

Tamil diaspora welcomes this gesture by the Government of Sri Lanka and it will do its part to help rebuild Sri Lanka and is committed to that. However, I truly believe the decline of Sri Lanka’s moral fibre represents the single most serious threat to its own survival. I’m afraid, at the core, Sri Lanka hasn’t changed, by electing the same type of politicians. It is doing the same thing over and again and expecting a different result.

What are the lessons that Sri Lanka can learn from Canada?

The true greatness of a nation—like Canada—is its willingness to accord to all communities and offer status and dignity equal to the majority, in order to weld those diverse groups into a harmonious polity. In this joust, a leader with this vision is pivotal. Unless, and until, Sri Lanka can produce leaders who can realise that truth, and are willing to act on it, it will continue to be dismembered by conflict and economic misfortune.

Q: What is the message for your readers?

A peaceful society cannot exist until there is racial equality, or at least a genuine attempt to address the central issues. I still maintain that war crimes charges on both sides are needed for reconciliation to happen. No matter if you are a Sinhalese or a Tamil, there is a basic universal truth: we always have more in common than different across all races, religions, and political ideologies. Instead of deepening your past divisions, you need to strengthen your present bonds.

Therefore, don’t allow these provocateurs who like to play with matches in the tinderbox of ethnic and religious confrontation to roam free in your beloved Sri Lanka. And, take your country back by putting some young, inspiring leaders with a vision, who can bring all communities together with one single goal of peace and prosperity for all. Take a page out of Singapore’s playbook.

Q: What is your memory of your father, who was your strength and your days in Point Pedro?

Whenever he visited Point Pedro on vacation, my father and I would be on our bicycles. I shadowed him everywhere he went, with puppy-like devotion as I idolised him. I loved biking around with him. Every street sign was faded by years of neglect and roads were pockmarked by shrapnel from exploded shells. But the heart of the town was untouched. We would pedal along the road that curved along the shore, with its shops and stalls as vibrant as they had been in peacetime. It must have been good for him to get away from Colombo. For me, these were moments to cherish.

Q: Is private sector participation vital for a country’s development?

The challenges facing a nation like Sri Lanka are too large to be tackled by public institutions alone. Achievement of sustainable development relies on all actors of society. All stakeholders: governments, civil society, the private sector, and others, are expected to contribute to the growth of an economy and a country. To that end, as the primary contributor to economic growth and employment creation, the private sector has a central and important role to play.