Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday, 29 October 2025 00:57 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

It is only through a transformed political outlook that breaks with nationalism and embraces solidarity across communities that we can build a strong, shared, egalitarian future

It has been 35 years since the Muslim communities of Sri Lanka’s Northern Province were evicted en masse by the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). This incident left a dark blot on the long history of Tamil–Muslim relations in the region and beyond. Many of the evicted Muslims went to Puttalam and the southern parts of the country, where they lived for years in camps for internally displaced persons. They faced severe economic hardship as they rebuilt their lives from scratch in unfamiliar surroundings. They also experienced social isolation, as host communities were not always welcoming of their prolonged presence.

Back in the north, their homes were left to ruin or occupied by displaced Tamils; their mosques fell into disuse; their shops were looted and their schools abandoned; and their lands came under the control of the Sri Lankan military. In their absence, the Northern Province became mono-ethnic. As stated in the Citizens’ Commission report released in 2012, the eviction of the Muslims should be understood as an act of ethnic cleansing. Here is a community that was forcibly uprooted from its homes and lands and rendered refugees. They were severed from the economic resources that had sustained them for centuries and denied access to the schools and mosques that formed the core of their cultural, religious, and social life. The magnitude of the social, cultural, and economic loss and dispossession suffered by the northern Muslims makes the eviction a clear act of ethnic cleansing.

Eviction and Tamil nationalism

While some tend to frame the eviction of the Muslims as merely another tragedy of the civil war, its roots are deeply ideological. Like many ethno-nationalist movements around the world that imagine land as an ethnic, racial, or cultural homeland, Tamil nationalism too claims Sri Lanka’s north-east as the Tamil homeland, a territory where Tamils, as a nation, have the inalienable right to determine their political future. This articulation is widely seen as a legitimate expression of the Tamil community’s desire for liberation in the face of Sinhala-Buddhist chauvinism.

While some tend to frame the eviction of the Muslims as merely another tragedy of the civil war, its roots are deeply ideological. Like many ethno-nationalist movements around the world that imagine land as an ethnic, racial, or cultural homeland, Tamil nationalism too claims Sri Lanka’s north-east as the Tamil homeland, a territory where Tamils, as a nation, have the inalienable right to determine their political future. This articulation is widely seen as a legitimate expression of the Tamil community’s desire for liberation in the face of Sinhala-Buddhist chauvinism.

To grasp the ideological thrust behind the eviction, one must unpack the territorial and cultural rationales that underpin discourses of self-determination both within and beyond the Tamil context. Since the early 20th century, the right of nations to self-determination has been invoked by marginalised communities as a politico-legal ideal in their struggles against colonialism and majoritarianism. Oppressed nations—or nations without State power—have deployed this right in their quest to gain sovereignty. Yet both liberal and leftist proponents of this principle have often failed to recognise the exclusivism inherent in many self-determination projects. They have overlooked how these projects, grounded in nationalist territorial constructions, transform multi-ethnic regions into the imagined homelands of a single group.

The eviction of northern Muslims and other forms of exclusionary violence that Sri Lanka and the rest of the world have seen should compel us to recognise that ethno-national articulations of self-determination, including those emerging from oppressed communities, are pregnant with the potential for genocide and ethnic cleansing.

It is no exaggeration to say that the ideological core of the eviction stemmed from Tamil nationalism. The LTTE, positioning itself as the sole representative and guardian of the Tamil nation, assumed the authority to decide who could inhabit the Northern Province and who could not. Although the movement later expressed regret for expelling the Muslims, its apologists continue to downplay this political crime. Some argue that the eviction was a reaction to the role of Muslim home guards aligned with the Sri Lankan state in the massacres that took place in pre-dominantly Tamil villages in Eastern Province. Others claim that some northern Muslims collaborated with the state, and the eviction was ordered by the LTTE as a counter-move.

The eviction of northern Muslims and other forms of exclusionary violence that Sri Lanka and the rest of the world have seen should compel us to recognise that ethno-national articulations of self-determination, including those emerging from oppressed communities, are pregnant with the potential for genocide and ethnic cleansing

These “explanations” fail to interrogate the political foundations from which the LTTE drew its authority to decide who could live in the North. That foundation was Tamil nationalism itself. This violence by a non-State actor mirrors the sovereign violence that nation-states often unleash against their minorities.

If we were to extend the LTTE’s logic and ask why Tamils were not similarly expelled, though some Tamils too collaborated with the State, we would uncover the politics of exclusion that underpinned both the LTTE’s vision of liberation and the broader ideology of Tamil nationalism. The uncomfortable truth, which eviction apologists often avoid admitting, is that for the LTTE and for the Tamil self-determination project, Tamil lives mattered more than others. Tamils were imagined as the rightful “people of the land”, entitled to self-determination, while others, including Muslims, were reduced to second-class inhabitants or expendable, expellable populations. This is no vision of liberation. It reveals instead a hierarchical ordering of populations structurally akin to the ideology that produces Sri Lanka as the land of Sinhala-Buddhists.

That we could not foresee that a liberation movement fighting a majoritarian state would itself expel a minority community within its territories should remind us of our failure to recognise that violence against the other is an imminent, latent component of all ethno-nationalist claims about self-determination. The explosion occurs when conditions on the ground are ripe as we saw in the case of the expulsion of the Muslims. The eviction offers us an important political lesson. It underlines the futility of distinguishing between progressive and oppressive nationalisms. It shows that such distinctions emanate from theories that have little historical basis and political paradigms that, deliberately or otherwise, valorise majoritarianism and nativism over coexistence and equality.

The eviction makes it clear that Tamil nationalism, like Sinhala-Buddhist nationalism, must be abandoned in its entirety. Attempts to reconstruct Tamil nationalism as Muslim-friendly, democratic, or progressive, or to encourage Muslims to present themselves as a separate nation seeking self-determination in Muslim-majority areas of the East will not lead to genuine political transformation. Such projects, rooted in the territorialisation of ethnic identities, are destined to reproduce conflict and exclusionary violence. To end the vicious cycles of ethno-nationalist exclusion that Sri Lanka has witnessed, a new political imagination of coexistence must be forged both at the centre and in the regions.

Return, resettlement, and the question of justice

Even as we examine Tamil nationalism’s complicity in the eviction, we must acknowledge the state’s failure to support returning Muslims. Although many have returned to the North since the end of the civil war, their resettlement has not been adequately facilitated. Land scarcity remains a serious issue, as families have grown during their thirty-year displacement.

In Mullaitivu, returning Muslims have reported difficulties in obtaining electricity for their homes and permission to dig wells for agriculture, as they lack official documents to prove ownership of the lands that they presently inhabit. The returnees had lost their documents during the war or the documents that they are now in possession of are deemed unacceptable by State authorities and local bureaucrats.

State financial support is barely sufficient to meet the basic needs of the community in an economic context adversely impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic and IMF-led austerity policies. In Mannar, Muslim women seeking livelihood opportunities have expressed the need for larger compounds for small-scale home-based production or poultry farming. They wish to balance economic participation with domestic responsibilities and seek access to low-interest credit for small industries. These experiences show that resettlement is not a homogeneous process; the aspirations of the returnees are shaped by their economic status and gender.

To facilitate genuine resettlement, institutional hurdles must be removed without delay. Land held by the military should be released, and the state must provide adequate economic assistance. Tamil officials administering the North should welcome the returning Muslims rather than viewing their return with suspicion or hostility.

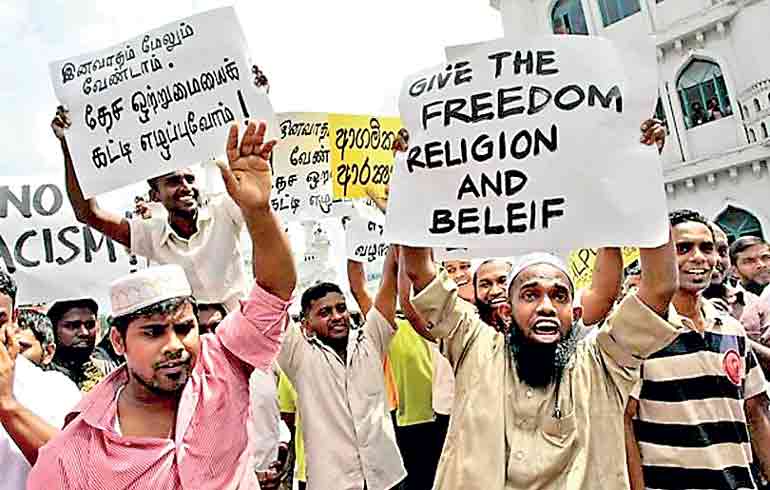

While negligence on the part of the State raises serious questions, social life for returning Muslims has also been fraught with challenges. There have been many incidents of discrimination over the past 15 years. When Muslim returnees attempted to reclaim their lands arbitrarily declared as protected forest reserves in Musali in Mannar district, they were branded as encroachers by chauvinistic groups in both the north and the south. Following the Easter Sunday attacks, some Jaffna-based newspapers published vitriolic editorials portraying Muslims and their religious leaders as fundamentalists and terrorist sympathisers. In some schools, Muslim girls faced pressure not to wear traditional attire. Scrap-iron collectors from the Muslim community faced violence in parts of rural Jaffna, and Hindutva elements in the North have targeted Muslim businesses. Though the anti-Muslim sentiments that emerged in the North following the end of the war were not as severe as the physical and discursive violence that Muslims suffered in the southern parts of the country, Muslims did go through periods of alienation and marginalisation in the north as well.

The question of social inclusion and the pursuit of justice for the eviction in such a fraught context are inseparable from the kind of future we envision for both northern Muslims and the Northern Province as a whole. Reimagining the province as a multi-ethnic, multi-religious region and a shared home for all its inhabitants is essential for any democratic and inclusive power-sharing arrangement. Frameworks of devolution must guarantee safety, dignity, livelihood opportunities, and equitable economic development for all minorities within the province.

Towards solidarity and coexistence

As we collectively remember the eviction, we must seek new ways to strengthen Tamil–Muslim relations in the north and beyond. Both communities—together with others—must work in solidarity to hold the State accountable for the ways it continues to marginalise them, sometimes by pitting one community against another.

Attempts to reconstruct Tamil nationalism as Muslim-friendly, democratic, or progressive, or to encourage Muslims to present themselves as a separate nation seeking self-determination in Muslim-majority areas of the East will not lead to genuine political transformation. Such projects, rooted in the territorialisation of ethnic identities, are destined to reproduce conflict and exclusionary violence. To end the vicious cycles of ethno-nationalist exclusion that Sri Lanka has witnessed, a new political imagination of coexistence must be forged both at the centre and in the regions

The NPP Government, while proclaiming itself minority-friendly, has been slow to release the land that Tamils and Muslims lost to militarisation. It has not taken any significant measures to curb the anti-minority agendas of the Archaeology, Wildlife Protection, and Forest Departments. The Prevention of Terrorism Act, which the NPP pledged to repeal before the elections, continues to be used to criminalise Muslims. The ongoing surveillance of journalists from minority communities further exposes the Government’s hollow commitment to pluralism. Minority communities must unite to resist these tides of exclusion.

Yet not all is bleak. Over the past fifteen years, there have been encouraging developments too. When the Tamil genocide monument at the University of Jaffna was demolished, Muslims joined Tamils in protest (it should be noted, that no commemoration for the eviction has yet been held at the university). Similarly, during anti-Muslim violence in 2014, 2018, and 2019, and when the state mandated the cremation of Muslim COVID-dead, Tamil civil society groups, activists, and political leaders, including those who are sympathetic to Tamil nationalism, stood in solidarity with Muslims. In 2021, the Pottuvil-to-Polikandy March brought the two communities together, highlighting their shared and separate struggles, though it was later undermined by unilateral attempts to prioritise Tamil nationalist demands.

Encouragingly, the cooperative sector in the North has shown eagerness to create livelihood opportunities for returning Muslim communities. Inter-ethnic initiatives such as the Jaffna People’s Forum for Coexistence and Vallamai (a women’s group for social change) foster dialogue between Tamils and Muslims and explore possibilities for collaboration beyond ethno-nationalist frameworks.

These efforts must be strengthened, deepened and expanded. Justice for the evicted Muslims encompasses all these processes and more and it must be admitted that we have a long way to go in this regard. It is only through a transformed political outlook that breaks with nationalism and embraces solidarity across communities that we can build a strong, shared, egalitarian future. It is to this vision of coexistence that we must commit ourselves today, as we commemorate the expulsion of the northern Muslims 35 years ago.

(The writer is a Senior Lecturer attached to the Department of Linguistics and English at the University of Jaffna.)