Monday Mar 09, 2026

Monday Mar 09, 2026

Friday, 13 September 2024 00:20 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Excessive money printing is harmful to the economy as it could fuel inflation caused by too much money chasing too few goods, and destabilise the economy

An evaluation one year into implementation of Central Bank of Sri Lanka Act

An evaluation one year into implementation of Central Bank of Sri Lanka Act

Introduction

Money printing, which is a popular jargon in Sri Lanka, broadly refers to the process by which the Central Bank issues fresh money to the economy. It is essential to increase the money circulated in the economy to match the value of overall transactions to facilitate increased activity, as the economy expands. However, excessive money printing is harmful to the economy as it could fuel inflation caused by too much money chasing too few goods, and destabilise the economy.

There are several methods through which money is issued to an economy. One major way is by the purchase of Government securities by the Central Bank. In the few years before 2023, the Central Bank purchased Government securities excessively. Referred to as monetary financing, this was carried out for the purpose of financing the deficits in the Government budget. However, the Central Bank of Sri Lanka Act No. 16 of 2023 (CBA), enacted in September 2023, prohibits monetary financing. Zero monetary financing has been possible since then–without disrupting Government functions–due to the improvements in fiscal performance under the fiscal consolidation programme implemented in line with the International Monetary Fund–Extended Fund Facility (IMF-EFF) program in 2023. In this context, this article discusses recent developments in money printing and monetary financing.

Enactment of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka Act (CBA)

The CBA is now the governing piece of legislation of the Central Bank, whereas the Monetary Law Act (MLA), which was in effect since 1949, was repealed with the introduction of the CBA. The key objective of this change in the law was to improve autonomy and accountability of the Central Bank, thereby improving the economic outcomes of the country and well-being of the people. The CBA prohibits monetary financing.

An autonomous central bank in a country is needed to separate the money printing function from the elected political leaders. Since political cycles are short, it is natural for elected political leaders to issue more money and boost the economy in the short run in order to support their re-election. However, the cost of such a temporary economic boost can be disastrous in the medium to long run. For example, printing money more than appropriate levels could simply increase price levels, thus destabilising the economy. The same was experienced during the recent economic crisis.

Prohibition of monetary financing

Monetary financing, i.e., the central bank financing of the Government budget deficit, has been one of the main criticisms against governments and central banks, as it fuels inflation. This is also a matter of fiscal dominance and fiscal indiscipline. The CBA prohibits monetary financing through eliminating purchases of Government securities in the primary market in Sri Lanka. In the repealed MLA, purchasing Treasury bills from the primary market was allowed. Another way of supporting government cash flow is the provision of cash advances to the Government by the Central Bank. Such provisional advances by the Central Bank to the Government at the beginning of the year when Government revenue collection is low, is still allowed under the CBA, but in significantly lower amounts and for a shorter period than under the MLA.

Under the repealed MLA, the Central Bank was allowed to make direct provisional advances to the Government, which should not exceed 10% of the estimated revenue of the Government for a given financial year, which was usually not paid off. However, under the CBA, provisional advances are limited, and should not exceed 10% of the Government revenue of the first four months of the preceding financial year. Further, the Government needs to settle such balances within six months, as per the CBA.

Ways of money printing

As stated at the beginning of this article, money printing is the process of providing fresh money to the economy by the Central Bank. This fresh money, which could be provided to finance the Government budget deficit (now prohibited), to facilitate central bank operations, or to match the value of overall transactions in the economy, would flow through the banking system to the broader economy. The Central Bank could issue new money to the economy by accumulating its domestic asset or foreign asset portfolios.

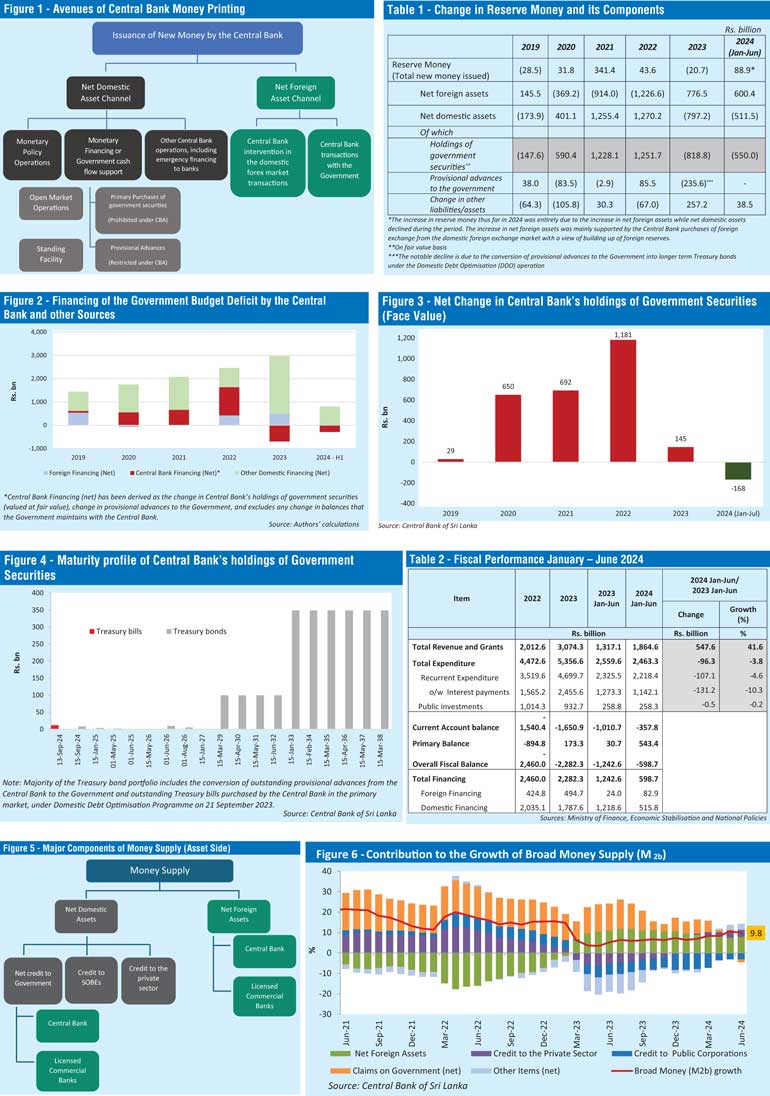

The Central Bank engages in money printing to facilitate its monetary and other operations. These operations include providing lending facilities to licensed banks including emergency funding, conducting open market operations, providing money for purchases of foreign exchange from the domestic foreign exchange market, and financing the Central Bank’s operational expenses. The major ways of money printing through such channels are presented in Figure 1.

Although the money printing to finance the government budget has been prohibited under the CBA, the Central Bank can provide fresh money to the economy in order to facilitate monetary policy and other Central Bank operations. However, such provision of fresh money to the economy has to be done after rigorous analysis, forecast, and assessment of the requirement.

A useful indicator for the gauging money printing is the change in Reserve Money or Base Money. The liability side of the reserve money consists of currency issued by the Central Bank, and deposits of commercial banks with the Central Bank, while the asset side of the reserve money consists of net domestic assets and net foreign assets. Changes in Reserve money and relevant indicators in recent times are given in Table 1.

Money printed for financing Government budget deficits

Following the outbreak of COVID-19 in Sri Lanka, the Central Bank had to provide monetary support to the Government through purchases of Government securities in the primary market as well as special purchases of government securities in order to meet urgent expenses of the Government. As a result of the continuous monetary financing at significant scales, the Central Bank’s holdings of Government securities had also increased substantially since 2020. This practice also partly contributed to the high levels of inflation that prevailed in recent years.

However, following the CBA, money printing for the purpose of financing Government budget deficits came to an end. With the support of the policy reforms under the IMF-EFF program and enhanced fiscal discipline, the Government improved its revenue and reduced expenditure. As a result, the Central Bank’s holdings of Government securities started to decline. Further, as per the maturity profile of government securities owned by the Central Bank, the entire stock of the Central Bank’s holdings of Treasury bills is expected to mature by 13 September 2024 (Figure 4).

One criticism against the restriction of monetary financing by law is that it could cause a possible complete shutdown of the Government in the absence of monetary financing–especially during large shocks like the COVID-19 pandemic, when Government revenue collection would be at bare minimum levels. However, under exceptional circumstances that substantially and materially disrupt or constrain access by the Government to market funding, with the approval of the Parliament, the CBA allows the Central Bank to purchase Treasury bills in the primary market. These extraordinary events include those that are in the interests of the public security and preservation of public order or a global health emergency. Provisions are also in place to ensure that such monetary financing is temporary and only used as contingencies.

Will monetary financing be required anymore?

Government budgets in Sri Lanka have been recording large deficits historically (an average of above 7% of GDP during 2000-2022), and have been financed by both domestic and foreign borrowings. However, with the diminishing of availability of foreign borrowings since 2020, they had to be financed heavily through domestic borrowings. The domestic market was not able to absorb such large finance requirements of the Government, as such resources were not available in the market. Therefore, since 2020, the Central Bank had to finance the government budget to reduce pressure on the domestic market and to maintain interest rates (see Figure 2). With a fiscal consolidation program, the Government is expected to continue to increase revenue, cut expenditure, and reduce budget deficits and record primary surpluses. Fiscal performance, especially Government revenue, has improved substantially during 2023 and thus far 2024, as shown in Table 2. With the continuation of a fiscal consolidation plan, the requirement of monetary financing is expected to be zero.

Money printing and growth of broad money supply

Broad money supply is the total amount of money available in an economy at a given point in time. This includes various forms of money such as cash and deposits that are created through changes in net foreign assets and net domestic assets of the banking sector. Commonly, the relationship between money printing by the Central Bank and the growth of broad money supply is as follows: when a central bank prints money, it increases the money supply. In simpler terms, when the Central Bank purchases government securities, it pays for such transactions with newly created money, which then gets deposited into the banking system and increases the amount of money circulating in the economy. However, the Central Bank does not have the direct control over broad money supply as it does with the reserve money or base money, as there are other contributors for the growth in money supply beyond Central Bank’s direct control. The major components of money supply are given in Figure 5.

The money created by the Central Bank is a single part of the broad money supply, which usually affects the net domestic assets of the banking system. Apart from the money creation by the Central Bank, the change in net foreign assets also contributes to the change in money supply. For instance, even if the Central Bank injects fresh money into the economy (which could increase net domestic assets), a simultaneous decline in net foreign assets could negate the impact of the former, thus moderating the growth of money supply.

On the other hand, the money that has been injected to the economy could be hoarded by the public and the banking system. This might not immediately change the money supply. If the demand for money is less in terms of credit to the private sector and investments in government securities and other instruments, then money would not be circulated at a high velocity in the economy, limiting the growth of money supply. Further, the Central Bank could use various tools such as adjusting policy interest rates, changing reserve requirements for banks and actively engaging in Open Market Operations to control the growth of money supply. Contributing factors for the recent changes to broad money growth are given in Figure 6.

However, under the Flexible Inflation Targeting (FIT), which is the monetary policy framework of the Central Bank at present, the Central Bank does not target reserve money or money supply, as was done under the monetary targeting framework, which was in operation before 2020. Instead, under FIT framework, the Central Bank directly targets inflation, at 5% levels.

Conclusion

The practice of money printing for monetary financing has been a contentious issue due to its potential to cause inflation. The CBA, which prohibits monetary financing, is a significant step towards enhancing the autonomy and accountability of the Central Bank. Monetary financing has been barred since the introduction of CBA, and fiscal performance has been improved through the IMF-EFF supported fiscal consolidation program. Continuation of a fiscal consolidation program and fiscal discipline is essential for smooth functioning of the Government, in the absence of monetary financing.

Related articles:

1.“Money Printing; Is There a Proper Control”, 2018, by Swarna Gunaratne, accessible at the Information Series section of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka website.

2.“Myths of Money Printing”, by Janaka Edirisinghe, 2023, accessible at the Information Series section of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka website.

3.“Why Do We Need Independent and Publicly Accountable Central Bank?”, 2023, by Dr. Sujeetha Jagajeevan, accessible at the Information Series section of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka website.

(Lasitha Pathberiya is an Additional Director of the Economic Research Department of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, who holds a PhD in Economics from University of Queensland, Australia. Shakthi Rajakaruna is a Senior Economist of the Economic Research Department of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, who holds a Bachelor’s Degree (Specialised in Economics and Statistics) from University of Peradeniya. The views presented in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily indicate the views and the opinion of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka.)