Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Tuesday, 13 July 2021 02:44 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

In Sri Lanka, the policymakers seem to have moved towards MMT-type macroeconomic management in recent times. A few months ago, Central Bank Governor Prof. W.D. Lakshman mentioned that domestic currency debt is not a huge problem for a country with sovereign powers of money printing as prescribed in MMT. State Minister Ajith Nivard Cabraal stated at a recent news briefing that money printing is permissible due to the drop in Government revenue

There is widespread criticism levelled against the authorities of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL) in recent weeks alleging that they have printed large quantities of money since early last year. While such criticisms cannot be totally ignored, the money printing numbers quoted by some critics are overestimated, as I pointed out in the last week’s FT column (https://www.ft.lk/opinion/Central-Bank-s-failure-to-respond-to-unfair-criticism-on-money-printing-is-questionable/14-720048).

There is widespread criticism levelled against the authorities of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL) in recent weeks alleging that they have printed large quantities of money since early last year. While such criticisms cannot be totally ignored, the money printing numbers quoted by some critics are overestimated, as I pointed out in the last week’s FT column (https://www.ft.lk/opinion/Central-Bank-s-failure-to-respond-to-unfair-criticism-on-money-printing-is-questionable/14-720048).

Nevertheless, the fact remains that increased lending to the Government by the CBSL since last year, seemingly following the so-called Modern Monetary Theory (MMT)-styled monetary policy, has led to a rapid increase in the issue of notes and coins, defined as currency. Such currency issues by a monetary authority are commonly known as money printing.

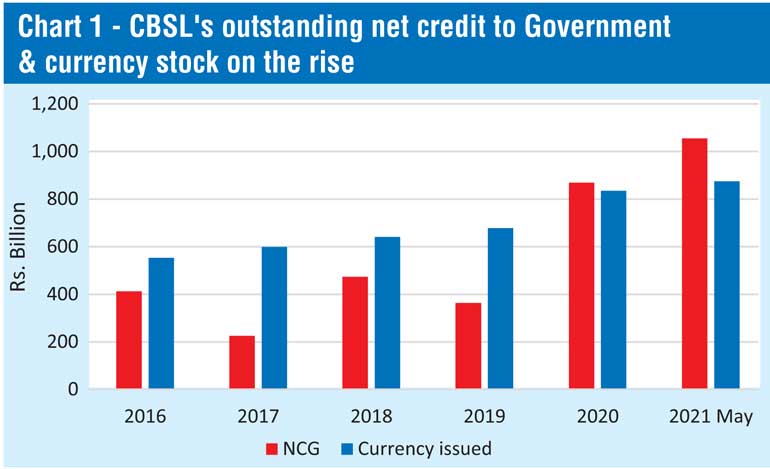

CBSL’s net lending to the Government rose by a whopping 176% year-on-year basis by January this year, resulting in a 31% increase in currency in the hands of the public. The outstanding stock of CBSL’s net credit to the Government now exceeds Rs. 1 trillion.

Apart from being a component of the aggregate money supply, currency functions as the monetary base for commercial banks to create credit by multiple times. Hence, the increase in currency issues in recent months has significantly enhanced market liquidity, and thereby created demand pressures fuelling price hikes and rupee depreciation.

What is MMT?

The notion that a sovereign government can print money to repay its debt without any financial limit has gained increased popularity in recent times in the US and in a few other countries, based on a new obscured approach to macroeconomics, known as Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). Money printing, rather than taxation, should be used to meet government expenditure, according to MMT proponents.

They argue that a government can never run out of cash, as it can repay its debts without any limit by getting the central bank to print new money, instead of resorting to taxation for revenue mobilisation.

This idea was developed by a few academics who broke away from mainstream economics. It became famous when some US politicians endorsed it, reinforcing their own accommodative monetary policy viewpoints. MMT is now gaining attention of the policymakers in some developing countries including Sri Lanka, as money printing is a convenient way to finance the budget deficits in the context of expenditure overruns and revenue shortfalls, amidst the COVID-19 pandemic.

SL moving towards MMT

In Sri Lanka, the policymakers seem to have moved towards MMT-type macroeconomic management in recent times. A few months ago, Central Bank Governor Prof. W.D. Lakshman mentioned that domestic currency debt is not a huge problem for a country with sovereign powers of money printing as prescribed in MMT.

State Minister Ajith Nivard Cabraal stated at a recent news briefing that money printing is permissible due to the drop in Government revenue. He pointed out that a new deal with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) would mean hiking taxes, apart from various other hostile conditionalities such as increasing interest rates, devaluing the rupee and cutting the number of state sector employees. CBSL Governor too ruled out any negotiation with the IMF at the Monetary Policy Review meeting held last week.

Thus, the policy stance preferred by the Government and the CBSL is to maintain a low taxation regime, and to meet the resulting budget deficit and debt obligations by printing money. This is exactly the policy mix suggested by MMT promoters.

Stephanie Kelton, a leading proponent of MMT, in her recent book titled ‘The Deficit Myth: Modern Monetary Theory and How to Build a Better Economy’ asserts that the way monetary sovereign governments should actually conduct expenditure is by simply creating the money for its spending by “a few key strokes” and not by using tax collections.

I pointed out the numerous perils of adopting such MMT policies in a country like Sri Lanka in a previous article published in this column (https://www.ft.lk/columns/Money-printing-to-repay-Govt-debt-worshipping-MMT-is-likely-to-magnify-economic-instability/4-710612). These adverse consequences have come to the surface by now, as predicted in the article.

Revenue shortfalls due to tax cuts

The Government knowingly or unknowingly laid the foundation for MMT-type fiscal policy by curtailing taxes in 2019. Immediately after the victory of the Presidential election in November 2019, the newly formed Government took steps to revise the Inland Revenue Act so as to provide a wide range of concessions to tax payers, without considering their adverse fiscal implications for monetary stability.

Accordingly, personal income tax rates, tax-free thresholds and tax slabs were relaxed significantly with effect from 1 January 2020. Also, Pay-As-You-Earn (PAYE) tax on employment receipts, withholding Tax and Economic Service Charge were removed effective from the above date. Downward revisions were made to the Value Added Tax and Nation Building Tax to stimulate business activities.

As a result of these tax cuts, the tax revenue declined by Rs. 518 billion or by 30% from Rs. 1,735 billion in 2019 to Rs. 1,217 billion in 2020. It resulted in an expansion of the budget deficit by Rs. 229 billion from Rs. 1,439 billion in 2019 to Rs. 1,668 billion in 2020.

Limited foreign borrowings

As the borrowing requirements of the Government rise continuously to meet the widening budget deficit, the authorities have been experiencing difficulties in mobilising borrowings from both foreign and domestic sources.

On the foreign front, the country’s sovereign rating downgrades effected by several international rating agencies have weakened the investor confidence in Sri Lanka’s bonds. This is reflected in substantial undersubscriptions in recent sovereign bond auctions. In the circumstances, the authorities have turned to obtain foreign loans in the form of swaps from China, Bangladesh and India.

Heavy reliance on CBSL’s lending

Heavy reliance on CBSL’s lending

Amidst foreign capital constraints, the Government started to raise more borrowings from the domestic money market through Treasury bills and bonds. It was reported that the Government intends to restructure public debt so as to change the domestic to foreign debt component from 55:45 in 2020 to 60:40 in 2021.

However, continuous increase in borrowings from the domestic market tends to raise interest rates causing difficulties in selling Treasury bills at lower rates. This is reflected in the recent Treasury bill auctions which were undersubscribed.

The total outstanding amount of Treasury bills stood at Rs. 1,759 billion by the end of April 2021, nearing the Treasury bill limit of Rs. 2,000 billion. This limit was raised to Rs. 3,000 billion last month so as to mobilise more Treasury bill borrowings.

The CBSL usually calls bids for Treasury Bills at weekly auctions. Treasury bills amounting to Rs. 56 billion are to be issued at the next auction to be held on 14 July. It is higher than the amount of Treasury bills issued at previous weekly auctions which amounted to around Rs. 40 billion. This reflects the increasing reliance on domestic borrowings.

The CBSL has been compelled to purchase the unsold Treasury bills at primary auctions. As a result, the CBSL now holds around 40% of the total outstanding amount of Treasury bills. This has resulted in a significant increase in currency issues.

Monetary base

The CBSL’s credit to the Government raises the money supply through its influence on the monetary base. It is also known as high powered money, since increases in the monetary base supports larger expansion of credit and money through the money multiplier.

On the liabilities side of the CBSL’s balance sheet, the monetary base comprises liabilities that support the expansion of credit and broad money. It includes currency outstanding and commercial bank deposits with CBSL. On the assets side, the monetary base consists of CBSL’s Net Foreign Assets (NFA) and Net Domestic Assets (NDA).

The monetary base rose from Rs. 932 billion in 2019 to Rs. 964 billion in 2020, resulting in an increase of Rs. 32 billion. On the liabilities side, currency issues rose by Rs. 156 billion while commercial banks’ deposits with the CBSL declined by Rs. 124 billion in 2020 due to a drastic reduction of the Statutory Reserve Ratio from 5% in 2019 to 2% in 2020.

The outstanding amount of currency rose by 23% from Rs. 678 billion in 2019 to Rs. 834 billion in 2020 (Chart 1). In other words, the CBSL issued new currencies amounting to Rs. 156 billion in 2020. This is the popular notion of money printing.

Monetary expansion

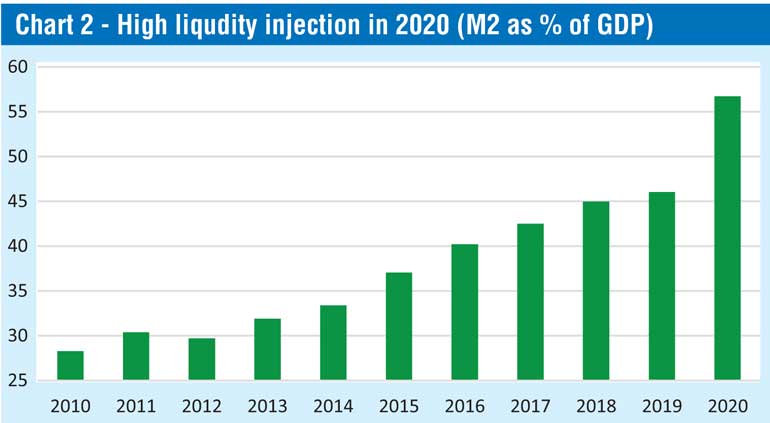

The broad money supply (M2), defined as narrow money supply (currency and demand deposits) plus time and savings deposits held by the public with commercial banks rose by 23% in 2020. This was due to a 117% increase in the NDA of the banking system mainly caused by the rise in Net Credit to the Government (NCG).

Around 98% of the increase money supply was on account of the substantial increase in NCG; net credit provided to the Government by CBSL and commercial banks accounted for 28% and 70%, respectively.

The Government obtained as much as Rs. 1,560 billion of net credit from the CBSL and commercial banks during the last 12 months. This reflects the extent to which liquidity is injected into the market by way of bank lending to the Government.

Adverse implications of MMT policies

As a result of the monetary expansion, the market liquidity, which can be measured in terms of the ratio of broad money supply (M2) to GDP, rose by 11 percentage points from 46% in 2019 to 57% in 2020 (Chart 2). This is an unprecedented increase in market liquidity. Demand pressures emanating from the excessive liquidity escalate inflation, weakening export competitiveness and encouraging imports, thereby widening the balance of payments deficit. This calls for further depreciation of the rupee giving rise to cost-push inflation.

The unprecedented rise in M2/GDP ratio also indicates that the country’s productivity growth is on a downward path. The higher the ratio the lower the productivity. This means that the country’s productivity does not grow proportionately to money supply increases. It is understandable, as bank credit is used to meet the Government’s debt obligations, rather than to fund efficient investment ventures. The lower productivity further widens the output gap in the backdrop of liquidity injections, and escalates demand pressures.

The adverse implications of MMT-styled fiscal and monetary policies are already reflected in price increases, income downfalls and rupee depreciation, which cause severe hardships for the people who are in the bottom of the income pyramid.

(The writer is Emeritus Professor in Economics at the Open University of Sri Lanka and a former Director of Statistics, Central Bank of Sri Lanka, reachable at [email protected])