Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Tuesday, 16 September 2025 00:23 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

|

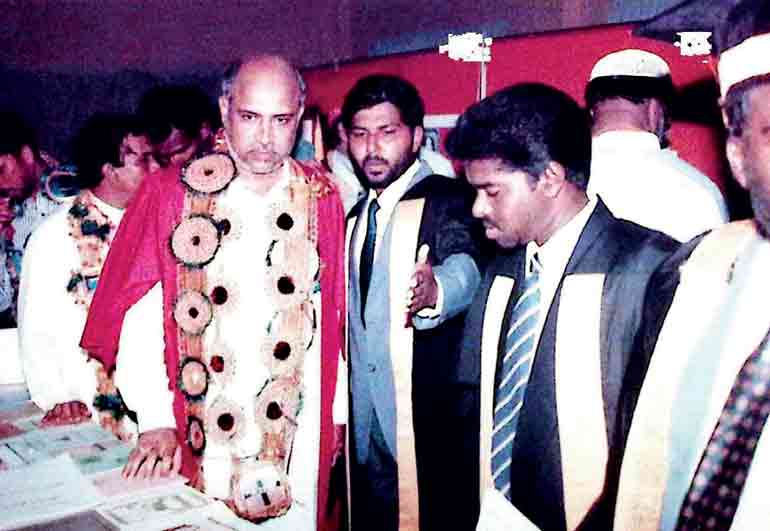

| M.H.M. Ashraff PC |

By Shaleeka Jayalath

When history remembers leaders, it often lists their victories, their alliances, or their parliamentary debates. But the truest measure of a leader lies in the legacy that endures long after their voice has fallen silent. On 16 September 2025, the day which marks the 25th anniversary of the passing of M.H.M. Ashraff PC, that is the very question that begs a response.

For Ashraff, his enduring legacy was neither in the party he founded nor the speeches he delivered. Rather, it was in the institutions he envisioned and enabled, the most notable of such achievements being the South Eastern University of Sri Lanka (SEUSL). Education was, for him, more than a policy matter. It was the foundation of empowerment, the key to dignity, and the one tool capable of transforming the lives of entire communities. In establishing the SEUSL at Oluvil, he did not merely create a campus. He opened a doorway for thousands who had, until then, been denied access to opportunity.

The significance of the impact made by the SEUSL was captured well by former Vice Chancellor, Prof. A. Rameez: “The establishment of the South Eastern University of Sri Lanka no doubt fulfilled the long sought out needs of the people of the South Eastern region. It coincided with the policy of the Government to make broad base education more accessible by extending it to less developed regions in the country such as the South Eastern region… We remain very grateful to late leader Ashraff for his service to uplift and empower the South Eastern community educationally; particularly the Muslim community.”

Symbol of inclusion

Today, SEUSL is home to nearly 8,000 internal students, a further 8,000 external learners, and close to 900 staff. But numbers alone do not tell the story. For the Muslim-majority Eastern Province, long marginalised during decades of conflict, the university became a symbol of inclusion. For parents who once feared their children had no future beyond subsistence, it offered hope. For youth caught between violence and poverty, it offered an alternative path.

Ashraff’s commitment to education was not separate from his politics. Rather, it was central to it. He understood that structural inequalities kept communities locked in cycles of disadvantage. He recognised that for the Muslims of the East, double minorities in relation to both the Sinhalese and Tamil ethnicities, empowerment could not stem merely from political representation. It had to be anchored in access to learning, professional skills, and upward mobility.

In this sense, the university was a radical project of justice. It was about giving those on the margins the same right to dream as those in Colombo. Yet, it would be a mistake to see Ashraff’s contribution to education as benefitting only one community. His vision was larger: to extend the reach of higher education into less developed regions, making opportunity a national resource rather than a privilege for the few. This inclusivity was no accident. It reflected his wider philosophy of acceptance and equality. As the founder of the Bureau of Inter-Religious Dialogue (BIRD), Ashraff believed deeply that true unity could not be legislated from above but had to be built in spaces where people studied, worked, and lived together. In this sense, the university at Oluvil was more than an educational institution – it was, in fact, an experiment in coexistence. By bringing Sinhalese, Tamils, and Muslims into a shared space of learning, Ashraff extended his lifelong commitment to ensuring that faith, ethnicity, and language would never again become barriers to opportunity. The SEUSL may have been born from the needs of the Muslim community, but its doors were never closed to others. Tamils, Sinhalese, and Muslims alike have walked its halls, studied side by side, and carried its degrees into professional life.

Transcend sectarian politics

Ashraff’s focus on education was consistent with his broader leadership philosophy. He had always believed that empowerment required structures, not slogans. Whether through the formation of the Sri Lanka Muslim Congress to give voice to the voiceless, or his efforts at constitutional reform to amplify minority representation, Ashraff looked for systemic ways to create change, first for the Muslim community, and then nationally with the formation of the National Unity Alliance, as he came to realise that to truly serve the nation, it was critical to transcend sectarian politics. With his vision for making lasting change at grassroot level, he designed what he believed would be a blueprint for achieving lasting peace in the nation by 2012. Nevertheless, the SEUSL was perhaps his most enduring systemic contribution. And today, a quarter century after his passing, and long after parliamentary seats have changed hands, the university continues to empower thousands of young people every year.

In an era where global conversations often centre on division, inequality, and exclusion, Ashraff’s example urges us to look again at the transformative power of education

It is easy to forget the context in which the vision of a tertiary institution for the Eastern Province was born. In the 1980s and 1990s, the East was a landscape of fear, its people trapped between the violence of the LTTE and the neglect of the State. For Muslims in particular, displacement and insecurity were daily realities. To speak of universities in such a climate was, in many ways, an act of defiance. It was a refusal to accept that an entire generation would be lost to conflict. Moreover, it was a declaration that learning rather than war, should shape the destiny of young people.

The university was a radical project of justice. It was about giving those on the margins the same right to dream as those in Colombo. Yet, it would be a mistake to see Ashraff’s contribution to education as benefitting only one community. His vision was larger: to extend the reach of higher education into less developed regions, making opportunity a national resource rather than a privilege for the few. This inclusivity was no accident. It reflected his wider philosophy of acceptance and equality

In an era where global conversations often centre on division, inequality, and exclusion, Ashraff’s example urges us to look again at the transformative power of education. It is not enough to expand universities in numbers alone. We must ensure that they remain accessible, inclusive, and true to their mission of lifting up those most in need.

Ashraff’s political life was not without controversy, nor was his leadership free of criticism. But leadership is rarely perfect. What matters is the intention and the impact. In founding SEUSL, Ashraff gave to the Eastern Province, and indeed to the nation, a gift that outlived him. For it is neither a fleeting policy or a party slogan but a lasting structure of opportunity, representing his conviction that education is able to do what politics alone never can: transform lives, expand horizons, and give dignity to the margins of society.

Twenty-five years on, the university continues to stand as proof that one leader’s vision, when anchored in justice and inclusivity, can outlive the battles of the day. It is a reminder that real nation-building happens not merely in parliaments but also in classrooms, libraries, and lecture halls where young adults shape their futures.

His legacy challenges us still: to build not only for the present, but for generations to come.