Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Monday, 22 November 2021 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

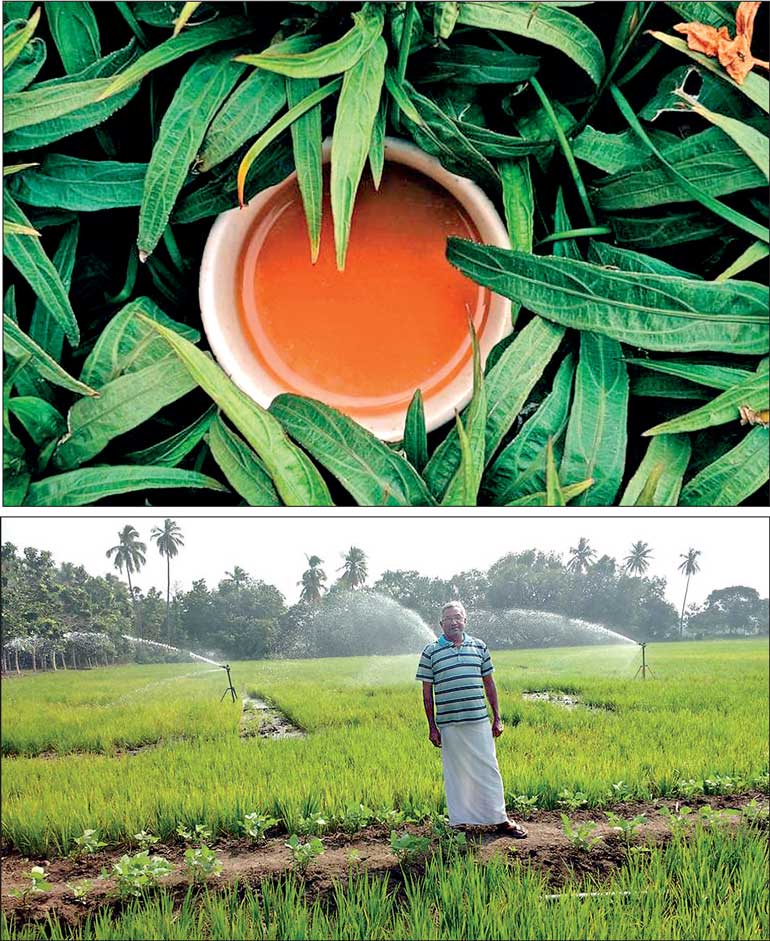

V. Ravichandran (GFN, India) on his farm

By V. Ravichandran

globalfarmernetwork.org: Sri Lanka has partially reversed a hasty decision to experiment with farming, but the country and its citizens are already paying for this bad mistake in the form of a food crisis.

President Gotabaya Rajapaksa announced a plan this spring to make Sri Lanka the first country in the world to ban inorganic fertilisers and crop-protection products that fight pests. This week, he changed his mind.

Yet as we commemorate World Food Day this month, we know that Sri Lanka is suffering from its original, anti-scientific choice: The Government recently declared a food emergency, imposing price controls and strict rationing. It forced farmers to sell their rice to a State agency and it has seized supplies from private warehouses. Meanwhile, Sri Lankans wait in line for hours to receive their portions of rice, sugar, milk powder, and other basic commodities.

This is what happens when a government pushes anti-scientific ideas onto farmers and consumers.

I’ve never visited Sri Lanka, which hangs like a teardrop off the southern coast of my native India, but it holds a special place in my daily routine: I drink its delicious tea every morning, as I begin to work on my farm.

Sri Lanka’s tea is perhaps the best in the world, due to the island nation’s favourable climate and long history of production. The country’s economy depends on these exports.

They are now in jeopardy, though the President’s change of heart may soften the blow. Organic tea is much more expensive to produce. Under a mandate, yields will plummet, and these producers will suffer significant consequences because of this disastrous policy.

Yet this crisis is about much more than tea: It has affected every sector of Sri Lanka’s agricultural economy, effectively paralysing the smallholder farmers who produce much of Sri Lanka’s rice, vegetables, and fruit. Even its natural rubber production may decrease. Sri Lanka’s Government decided to go backward into primitivism at a time when farmers around the world are surging forward with new technologies that help us grow more food on less land than ever before. Through remarkable advances in everything from plant genetics to precision irrigation to satellite imagery, we’ve become better and more sustainable producers.

If we were to apply Sri Lanka’s strange thinking on agriculture to communications, for example, we’d relinquish our mobile phones and turn to carrier pigeons. Instead of emails, we’d send handwritten letters. Rather than learning about the news from televisions and radios, we’d wait a long time for the news to reach us and perhaps not hear it at all.

When President Rajapaksa introduced his organic-farming rules, he boasted that no other country had ever tried such a thing. What he failed to understand is that most other countries already knew that this was a misguided and unscientific idea voiced by anti-development activists.

At least he is now beginning to understand his mistake.

Sri Lanka’s organic-farming blunder hardly could have come at a worse moment. COVID-19 has hurt economies everywhere, and it has taken a special toll on those that rely on tourism. After booming in the first part of this century, tourism in Sri Lanka has dropped sharply. This is partly the result of terrorist attacks on Christians in 2019, but mostly because of the pandemic. Foreigners have stopped flocking to its beaches, scuba-diving destinations, and natural beauty.

The value of its currency also has fallen, making it harder for Sri Lankans to purchase the goods and services they need from their international trading partners.

Compounding the problem is the logjam in the global supply chain, as container ships sit outside ports. Everything from semiconductors to medical devices is in short supply. The most tragic aspect of Sri Lanka’s food crisis, however, is that much of it was avoidable. In choosing to push its agricultural mandates, the Government refused to listen to the warnings of farmers.

I know that my farm couldn’t operate under Sri Lanka’s ridiculous rules. My yields of rice, cotton, and other crops would decrease significantly. The result would be simply disastrous.

If India’s population of more than one billion people were ordered to adopt the organic regulations thrust upon Sri Lanka’s 22 million people, we’d witness a catastrophe of malnutrition and starvation like the world has never seen. Our economy would crumble, and we would exhaust our foreign-exchange resources to feed our huge population, diverting our national wealth and stalling all other developmental activities. Finally, we’d have to expand our arable land by converting forest land for farming purpose, chopping down countless trees and global warming.

I don’t wish even to imagine such dreadful conditions.

It took only six months for Sri Lanka to begin to recognise that its organic-farming mandates are a massive failure. The lesson is to let farmers make judicious use of organic and chemical inputs, used in combination with other important technology options such as integrated pest, water and disease management practices. Trust science and technology so that its farmers and citizens stop paying a price they can’t afford.

Let the policy makers of all other nations understand the realities of Sri Lanka’s man-made disaster.

(Source: https://globalfarmernetwork.org/2021/10/we-must-learn-from-sri-lankas-man-made-organic-agriculture-disaster/)