Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Wednesday, 4 June 2025 00:28 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

To break the culture of excluding the people from law-making, it is imperative that the Government adopt a robust process that is consultative, transparent and accountable

Law-making in Sri Lanka is shrouded in secrecy, ambushes the general public and alienates people. The process of law-making, as practiced by successive Governments, is rarely open, transparent and accountable – beyond observing the processes minimally set out in the Constitution and Standing Orders of Parliament. As a consequence, Sri Lanka has enacted many bad laws, most recently the Online Safety Act of 2024, and continues to maintain many dangerous ones, including the egregious Prevention of Terrorism Act of 1979 which is used to harass and harm people to date.

Law-making in Sri Lanka is shrouded in secrecy, ambushes the general public and alienates people. The process of law-making, as practiced by successive Governments, is rarely open, transparent and accountable – beyond observing the processes minimally set out in the Constitution and Standing Orders of Parliament. As a consequence, Sri Lanka has enacted many bad laws, most recently the Online Safety Act of 2024, and continues to maintain many dangerous ones, including the egregious Prevention of Terrorism Act of 1979 which is used to harass and harm people to date.

In this context, it is necessary to examine the law-making process in Sri Lanka to demonstrate how it fails to be open, consult the people and be responsible for the impact that laws have on people’s lives. This article also presents some recommendations to change the current undemocratic system that mocks the notion that sovereignty lies in the people.

Between 2022 and 2024, Sri Lanka witnessed a frenzy of law-making by a parliament that clearly did not have the popular support of the people, with over 100 new laws including amendments enacted. The then Secretary to the Ministry of Justice, Prison Affairs and Constitutional Reforms, M.N. Ranasinghe declared that ‘the period from 2022 to 2024 will be historically significant for the highest number of law reforms in Sri Lanka’. This highlighted how the parliament, in both law and practice, is able to formulate and enact laws without any involvement of the people.

The lack of legal requirements and culture of governance that valued public consultation saw the economic crisis weaponised to create an unprecedented number of laws that failed to secure citizens’ socio-economic rights. It brought the lack of people-centeredness in lawmaking into sharp focus, juxtaposed with the Sri Lankan public’s call for ‘system change’ at the time.

Today, the NPP Government has come into power on a manifesto that promises at least 46 law reform priorities and 20 proposed laws to establish various national institutes, regulatory bodies and commissions. President Anura Kumara Disanayake made references to more than 10 new laws in his Budget speech in February 2025. In a Sri Lankan context of a history of law-making that has alienated the people, getting the law-making process right will be fundamental to the NPP Government delivering real change. This means liberating the law-making process from being the domain of an elite few, and adding checks and balances on even the Government’s own legislative aspirations by engaging the people throughout, from the point of conceiving a law to refining it after it has been enacted.

The NPP Government is currently operating within a longstanding institutional culture and legal framework that is weak on consultation, transparency and accountability. It is also operating through State administrative machinery which, by default, is secretive, shaped by certain individuals’ worldviews, allows access only to an elite few, and adopts an ‘officials know best’ attitude. To break the culture of excluding the people from law-making, it is imperative that the Government adopt a robust process that is consultative, transparent and accountable.

The current law-making system – no transparency, no accountability

The current law-making system – no transparency, no accountability

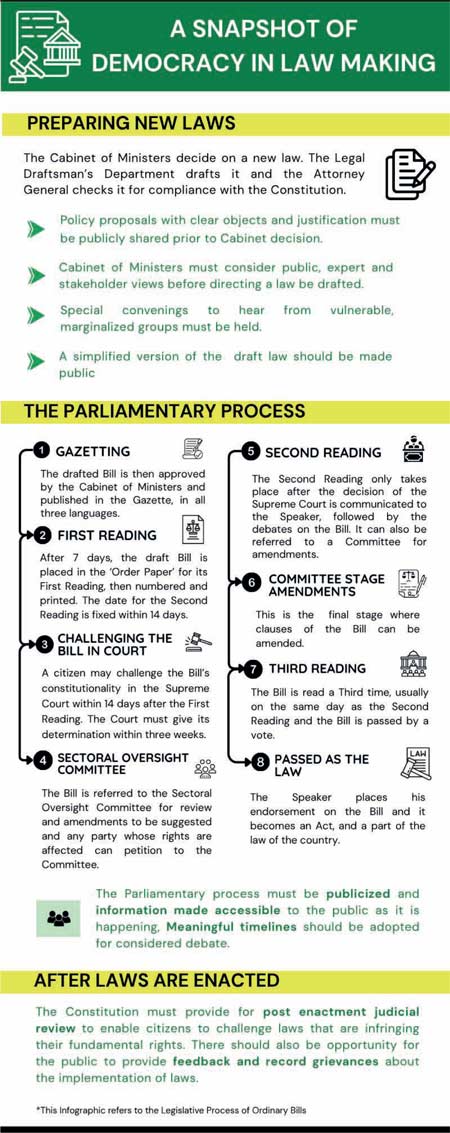

The legislative process in Sri Lanka has two main stages, the pre-Parliamentary stage and the Parliamentary stage. The former stage involves preparation and the drafting of the new legislation. The Ministry which is hoping to introduce a new law or make an amendment to an existing law prepares a Cabinet Memorandum and obtains approval from the Cabinet of Ministers. Once Cabinet approval is given, the Legal Draftsman is directed to prepare the draft legislation in line with the approved objectives. When the draft legislation is confirmed by the requesting Ministry to be in compliance with its policy, it is sent to the Attorney-General to consider if it is consistent with the Constitution. The final draft is then translated into Sinhala and Tamil and sent to the requesting Ministry.

The pre-Parliamentary stage is where the government of the day would be able to engage the people fully in consultation. And yet, this is the stage that is most shrouded in secrecy in Sri Lanka. Concept papers, policy papers and legislative proposals are almost never shared or discussed with the public.

For ordinary laws, as opposed to urgent laws, once the draft Bill is approved by the Cabinet of Ministers, it is published in the Gazette in all three languages, at least seven days prior to being placed on the Order Paper of the Parliament. Any time after the seven days, the draft Bill may be placed on the Order Paper for the First Reading of the Bill in Parliament. It is introduced, ordered to be printed in the form of a Bill and assigned a number. The Second Reading is usually fixed fourteen days after the First Reading. Upon the First Reading, within the fourteen days the Bill may be challenged by a citizen filing a petition before the Supreme Court in terms of Article 121 of the Constitution.

A citizen may challenge specific provisions or the whole Bill only by demonstrating that those parts are inconsistent with the Constitution. The Bill cannot be challenged on the basis that a better policy direction is available or that the scheme of the Bill is detrimental to the interest of any one or more persons. If challenged, the Second Reading of the Bill can only be fixed after the Supreme Court makes its determination on the Bill. The Court’s determination is communicated to the Speaker and is announced in Parliament, and until then, Parliamentary proceedings related to the Bill are halted. The assumption is that the legislature will act in accordance with the determination of the Supreme Court, however there is no check on this.

This facilitated the Online Safety Bill to be passed into law without adhering to the views of the Supreme Court. Before the Second Reading, the Bill is reviewed by a Sectoral Oversight Committee of Parliament. The Standing Orders of Parliament permits any party whose rights are affected by the Bill to petition the Committee. However, these opportunities are not made publicly known and are not easily accessible to citizens. Once approved by the Sectoral Oversight Committee, the Bill is fixed for its Second Reading. After the Second Reading, the Bill may be referred to a Committee for amendments.

The Constitution requires any amendments proposed to a Bill not to deviate from its merits and principles to protect the Bill from substantive changes being made. The Bill, with the amendments proposed at the Committee stage, is read a Third and final time and may be passed by Parliament by a vote. In Sri Lanka, the third reading takes place soon after the second reading, usually on the same day. The Bill becomes an Act when the Speaker endorses a Certificate that the new Act has been duly passed by Parliament.

It is clear from the processes described above, that the only legal requirement to make proposed legislation publicly accessible is during the Parliamentary process - when the Bill is published in the Gazette in three languages at least seven days prior to it being tabled in Parliament. The process described above has no legal requirement, during the pre-parliamentary process, to publicly share policy directions on proposed law reforms, conduct public consultations, especially consult with those affected and to be affected, undertake and publicise impact assessments and justify the chosen decision for legislative reforms.

The process as it stands essentially allows for a law to be passed in just under two months, even if challenged before the Supreme Court. As such, the law-making process as adopted by elected representatives and as experienced by citizens is sorely lacking in transparency and engagement with the people.

Recommendations for centring people in law-making

All organs of Government are in the service of the people. This basic safeguard ought to undergird the entire legislative process. The Constitution explicitly states that the people are sovereign, meaning power is ultimately in their hands. This means that people should have opportunities at all stages of law-making to ensure that law reform serves them and is not adverse to their interests. A sovereign people must be able to (1) initiate new laws, (2) interact with proposed laws and (3) prompt revisions to existing laws. Below are the stages at which people’s engagement could, and arguably should, be secured under the current legal framework.

Proposing new laws

There is no barrier to the Government of the day publishing their policy paper or concept paper for any new law reform they are contemplating and calling for the public to share their view within a reasonable period. Openness and transparency require that the Government is open about their policy priorities, the scheme of the new law reform that they propose and the justifications for the proposal. The Government must base their proposed law reform on an understanding of the problem to be addressed, available data and an appreciation of the law reform options available. It is only by having access to this information that people can constructively and confidently engage with the law reform process.

It is also important to actively engage specific stakeholders who may not have easy access to consultative spaces, to ensure that societal inequalities do not prevent inclusive public consultation. For example, victims of domestic violence must be consulted before law reform to the Prevention of Domestic Violence Act is undertaken. There must be safe spaces created, adequate time given and information submitted made accessible to decision makers and also to the general public.

It is only after a rigorous process of information sharing and consultation that the relevant Minister should articulate an informed direction for a new law and the Cabinet of Ministers take a decision to endorse the initiation of drafting a new law.

Drafting new laws

Once a first draft of a new law is available, it is important to make it publicly available together with easy-to-understand information on the new law. When unveiling the Budget 2025, the government published a document titled “the Citizen’s Budget” which simplified and summarised the key information in the Budget. Adopting a similar approach to drafted bills will enhance public understanding. A sustained commitment to openness will build public confidence in the law-making process. Opportunity must also be provided for the public to provide their views. A process by which these views are reviewed and draft laws are adjusted is a critical stage. It is likely that this process alone might take three months or longer to ensure optimal public engagement.

Once a draft law is revised under the direction of the relevant Ministry, having heard the submissions of the public over an extended period of time, it will be ready to be placed before the Cabinet of Minister for approval to be then placed before Parliament.

Parliamentary process

The parliamentary process provides further opportunity for elected representatives of the people to debate the law. Members of parliament, ideally informed by their constituencies or moved by their own expertise, can contribute to the shaping of the new law. Once the first reading is done, there is opportunity for citizens to challenge the law before the Supreme Court on concerns that any one of the provisions of the proposed law are inconsistent with the Constitution. This is a very specific challenge and it is concerned only with the constitutional guarantees of the Bill. Therefore, it is only at the pre-parliamentary stage that policy directions and lived reality impacts of the proposed law can be thoroughly examined and debated.

Thereafter, in the second and third readings in Parliament, the representatives of the people have the opportunity to debate and propose suitable amendments to ensure that no harm, inequality or injustice is facilitated by the proposed law.

People’s engagement after laws are enacted

Currently, there are no formal procedures or spaces for citizens to complain or provide information on how the implementation of any particular law is affecting them. Campaigns by civil society groups, and elite access to parliamentarians have been the only means of prompting amendments or changes to laws. Citizens are at a disadvantage, only able to react to law reform when it becomes public, often as a fully formed law, towards the end of the law-making process. In this context, citizen-driven law reform is nearly impossible.

Any reform of an existing law usually requires the entire law-making process to be triggered, which is often too high a barrier for a citizen legitimately raising a grievance relating to a law. People cannot complain to court about their rights being infringed by a particular law because Sri Lanka does not permit such complaints. These challenges may be addressed by establishing a mechanism for receiving public views on the implementation and failings of existing laws, and directing the relevant Ministries to consider initiating appropriate reforms.

While many countries provide for citizens to bring cases before the judiciary to challenge legislation even after enactment, Sri Lanka’s current Constitution does not allow its citizens to exercise the people’s sovereignty in this way. It is imperative that future constitutional reform provides for post-enactment judicial review of laws.

Conclusion

Ensuring truly democratic law-making is not complicated—it simply requires the political will to share power with the people who have granted it in the first place. It means accepting that officials do not always know best, that citizens have perspectives worth hearing, and that better laws emerge from open debate rather than from closed rooms. It is also the only way to restore public trust in state institutions that have been corrupted, co-opted and rendered incompetent for too long.

The current legal framework does not present any specific barriers to public engagement and consultation at each stage of the law-making process. What is missing is the political commitment to ensure this takes place.

Sri Lanka’s people are sovereign. It is about time that the law-making process reflected that reality.

(Ermiza Tegal is an Attorney at Law and human rights activist with close to 20 years of experience in human rights and governance. Nisara Wickramasinghe is an attorney at law and researcher. This article draws on research supported by the Law and Society Trust, Colombo, Sri Lanka.)