Friday Mar 13, 2026

Friday Mar 13, 2026

Tuesday, 20 January 2026 04:28 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Singapore’s economic success is one that many countries including Sri Lanka, sought to emulate

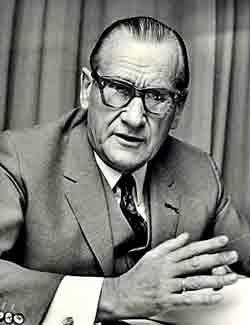

Year 2026 marks the 30th anniversary of the passing of Dr. Albert Winsemius, Singapore’s first Chief Economic Adviser and a guiding force behind its transformation

The year 2026 marks the 30th anniversary of the passing of Dr Albert Winsemius, Singapore’s first Chief Economic Adviser and a guiding force behind its transformation. Winsemius was a Dutch economist whose influence on Singapore’s early development is difficult to overstate. First appointed in 1960 as head of a United Nations Development Program mission, he went on to work closely with the country’s founding leadership, particularly Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, shaping the institutional and policy foundations of what would become one of the most successful economic reorientations of the post-war era.

The year 2026 marks the 30th anniversary of the passing of Dr Albert Winsemius, Singapore’s first Chief Economic Adviser and a guiding force behind its transformation. Winsemius was a Dutch economist whose influence on Singapore’s early development is difficult to overstate. First appointed in 1960 as head of a United Nations Development Program mission, he went on to work closely with the country’s founding leadership, particularly Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, shaping the institutional and policy foundations of what would become one of the most successful economic reorientations of the post-war era.

Before I entered public life, I first met Dr Albert Winsemius in The Hague, where he was then living in retirement. This was in the mid-1980s, when I was in my twenties. I have distinct memories of him — his simplicity, clarity of mind, and conviction left an indelible impression. He was not one for grand gestures or self-promotion; his approach was disciplined and precise, reflecting a distinctly Dutch pragmatism rooted in logic rather than ideology.

At that time, my late father was residing in The Hague. Having read extensively about his pivotal role in Singapore’s rise, I was keen to learn from his experience. A close friend of my father’s — a senior Dutch diplomat who headed the Queen’s household — arranged an introduction. That meeting marked the beginning of several illuminating conversations during my subsequent visits to the Netherlands.

What impressed me most was his rare ability to distil complex economic challenges into simple conceptual frameworks and propose solutions that were both principled and practical. Yet he was no mere technocrat. He believed that growth and opportunity were the most effective means of reducing hardship and restoring dignity — a conviction that gave economic policy its moral core.

On one occasion, Winsemius recalled his first visit to Singapore in 1960, at a critical juncture in the island’s history. This assignment marked the beginning of an extraordinary association with Singapore, which evolved into a role spanning more than two decades — nearly 25 years — during which he advised the government and helped shape long-term economic strategy.

As we chatted in his living room, Winsemius rose and pointed to a world map on the wall. His finger traced a line from Singapore to Dubai, then paused over Colombo. “There is a big gap here,” he observed, suggesting that Sri Lanka’s future lay in becoming a gateway to South Asia and beyond — but only if it acted decisively. More than three decades later, sadly, that potential remains unrealised

Drawing on his experience in the post-war Netherlands — where he had been involved in attracting multinational corporations such as Unilever and Shell — he discerned clear parallels between Holland and Singapore. Prior to the discovery of natural gas, the Netherlands shared with Singapore — and, in important respects, with Sri Lanka — the characteristics of a small economy without major extractive resources, compelled to rely on openness, efficiency, and strategic foresight to remain economically relevant.

In a competitive world, Winsemius believed that speed, decisiveness, and integrity were the lifeblood of effective investment promotion. Foreign investors, he would often note, required both efficiency and certainty. To this end, he strongly advocated the creation of a “one-stop agency” so that investors did not have to navigate multiple ministries. This recommendation led directly to the establishment of the Economic Development Board in 1961 — an institution that became central to Singapore’s economic success and one that many countries, including Sri Lanka, later sought to emulate.

Dr Winsemius emphasised that Singapore’s success rested on the vision, integrity, and resolve of its founding leaders — and on the trust the Singaporean people placed in them. He regarded this bond between leadership and citizenry as the true foundation of national development

For Dr Winsemius, competitiveness had to be actively tended and nurtured through constant attention to labour, infrastructure, taxation, and governance. Decision-making, he argued, needed to be agile and forward-looking while maintaining predictability and trust; stability and social cohesion were preconditions for sustained investment.

Above all, he emphasised that Singapore’s success rested on the vision, integrity, and resolve of its founding leaders — and on the trust the Singaporean people placed in them. He regarded this bond between leadership and citizenry as the true foundation of national development.

He once mentioned that Prime Minister Lee would sometimes ask officials to set aside certain problems until his next visit — a reflection of the extraordinary trust and intellectual respect placed in him. He was valued precisely for his detachment and objectivity: an adviser without personal or ideological agendas, who spoke with clarity and conviction.

That closeness endured long after his formal advisory role had ended. When Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew passed away in 2015, Dr Winsemius’s children were invited to attend the funeral as family guests — a quiet but telling indication of the esteem in which he continued to be held.

Winsemius believed that speed, decisiveness, and integrity were the lifeblood of effective investment promotion. Foreign investors, he would often note, required both efficiency and certainty

Even in retirement, Winsemius remained closely engaged with developments in Singapore. He once recalled how The Straits Times was sent to him regularly by the Singapore Government via the national carrier so that he could remain abreast of developments there — his intellectual engagement with Singapore never diminished.

|

| Dr. Albert Winsemius |

During one of my visits to Singapore, he arranged for me to meet several of his former colleagues from the early years. Those conversations deepened my understanding of how ideas were translated into practice — and how disciplined execution proved as critical as visionary design.

In one of our later conversations, Winsemius drew a compelling parallel between Holland and Singapore. Post-war Netherlands had deliberately positioned itself as Europe’s distribution hub, leveraging Rotterdam Port, Amsterdam Airport, and an integrated network of roads, railways, and pipelines. Singapore, he observed, had made a similar strategic choice for East Asia. He believed Sri Lanka could one day play a comparable role for South Asia.

I vividly recall one of my last meetings with him in early 1991 when I was responsible for coordinating the visit of Ranil Wickremesinghe, then Leader of the House and Minister of Industries, Science and Technology, to the Netherlands.

Having heard much from me about Dr Winsemius, Wickremesinghe expressed an interest in meeting him, and we visited his apartment. As we chatted in his living room, Winsemius rose and pointed to a world map on the wall. His finger traced a line from Singapore to Dubai, then paused over Colombo. “There is a big gap here,” he observed, suggesting that Sri Lanka’s future lay in becoming a gateway to South Asia and beyond — but only if it acted decisively. More than three decades later, sadly, that potential remains unrealised.

When Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew passed away in 2015, Dr Winsemius’s children were invited to attend the funeral as family guests — a quiet but telling indication of the esteem in which he continued to be held

Dr Winsemius passed away in December 1996. Four years later, when I entered active politics and subsequently served as a Cabinet Minister, I often found myself recalling his counsel — his insistence on clarity, focus, and pragmatic detachment.

He was, in every sense, a bridge between ideas and action — between vision and execution in public policy. In an era of technological disruption, demographic change, and geopolitical flux, Dr Winsemius’s insistence on clarity of policy, institutional strength, and disciplined execution remains instructive.

(The author is a former Sri Lankan cabinet minister and diplomat, and founder of the Sri Lankan strategic affairs think tank, Pathfinder Foundation, Can be Contacted via [email protected])

For Dr Winsemius, competitiveness had to be actively tended and nurtured through constant attention to labour, infrastructure, taxation, and governance. Decision-making, he argued, needed to be agile and forward-looking while maintaining predictability and trust; stability and social cohesion were preconditions for sustained investment