Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Thursday, 28 August 2025 00:39 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

It boosts accountability, especially in public institutions where taxpayer money is involved

Introduction

The fingerprint system uses biometric fingerprints. In simple terms, it’s a biometric time-tracking system designed for fairness and accountability in various professions. Scanners can record their attendance at workplaces or institutions. Instead of just signing a register or calling out names, employees need to scan their fingerprints to verify their presence. The goal is to prevent proxy attendance (someone else signing in for you). This ensures accurate records of who is there and for how long.

It also boosts accountability, especially in public institutions where taxpayer money is involved. Additionally, it can help (i) reduce absenteeism, (ii) reduce false overtime claims, and (iii) reduce misuse of public funds. In short, it’s a biometric time-tracking system created for fairness and accountability across professions. This system is used in other countries, such as India, Malaysia, and New Zealand.

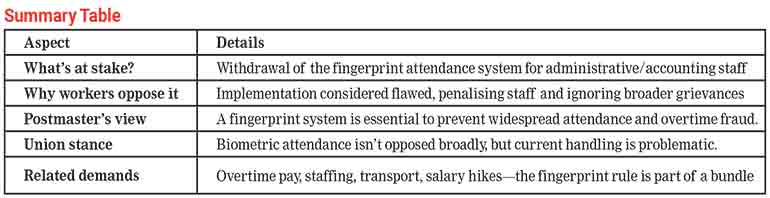

What the workers are opposing

The postal workers are protesting the implementation of a new mandatory fingerprint attendance system, especially for administrative and accounting staff. The unions argue that this system is unfairly penalising staff, especially when operational realities aren’t considered. Their demand for withdrawal comes alongside other grievances like inadequate overtime pay, staff vacancies, transportation issues, and salary increments.

The postal workers are protesting the implementation of a new mandatory fingerprint attendance system, especially for administrative and accounting staff. The unions argue that this system is unfairly penalising staff, especially when operational realities aren’t considered. Their demand for withdrawal comes alongside other grievances like inadequate overtime pay, staff vacancies, transportation issues, and salary increments.

According to the Postmaster General, the fingerprint system was introduced to curb abuses, such as overtime claims without proper attendance logs. Audits revealed many employees drawing salaries and overtime without using fingerprint scanners. Instead, they were signing attendance books, which allowed manipulation. Given the above, the system aims to enforce accountability and prevent irregularities at locations like the Central Mail Exchange, which had significant misuse of attendance recordings.

However, from the union perspective, it is not a new opposition, but a broader frustration. Interestingly, unions clarify that they do not fundamentally oppose biometric systems—noting that fingerprint machines have been in use for years across many administrative offices. Their opposition seems triggered explicitly by issues such as (i) how the system is implemented or enforced (perhaps without sufficient training or infrastructure). Also (ii) perceptions that it’s being used punitively without addressing broader concerns, such as low take-home allowances and insufficient staffing.

The postal strike started around 17 August, prompted by 19 demands, including the fingerprint issue. Over 18,000 workers are involved, with more than 1.5 million letters and parcels delayed across the system. Other key demands include reforming overtime pay, filling vacant positions, multiple pay increases for frontline workers, and fixing transport-related problems.

Indeed, the concerns mentioned above are worth discussing to find a constructive solution. However, launching a strike is not the answer either. It will likely disrupt the country’s economic growth momentum. The Government’s costs could eventually reach billions.

Comparison with three other countries

1.India

System:

India introduced the Aadhaar-based Biometric Attendance System (BAS) for central government employees in 2014. Employees log in and out using fingerprint or iris scans linked to their Aadhaar ID.

Cost:

Initial rollout was relatively low-cost — fingerprint devices are about $ 100–300 each, plus server and software costs. India scaled it massively because Aadhaar (national ID) already existed.

Benefits:

Sharp drop in absenteeism in ministries and public offices.

Real-time online dashboards show attendance data to the public (transparency).

Reduced “ghost employees” (fake workers drawing salaries).

Issues:

Some staff complained about privacy.

Technical issues in rural areas (connectivity, fingerprint mismatches for manual workers).

2.Malaysia

System:

Many government offices and hospitals use fingerprint or facial recognition systems for civil servants. Some universities also use biometrics for staff and student attendance.

Cost:

Medium — Malaysia spent around $ 20–30 million for nationwide public sector biometric upgrades in the 2010s.

Benefits:

Payroll efficiency — prevents overtime abuse.

Professional discipline — reduced late arrivals and early departures.

Issues:

Trade unions argue that over-monitoring reduces trust and morale.

Some say it treats professionals (like doctors and professors) the same as clerical staff, which may not be fair.

3.New Zealand

System:

New Zealand does not have biometric attendance in Parliament or across the public service. Instead:

Hansard records and voting participation track MPs’ attendance.

In government departments, flexible work arrangements are standard, and supervisors, not biometrics monitor attendance.

Some private companies use fingerprint or facial scanners for payroll integrity.

Cost/Philosophy:

NZ prefers a trust-based accountability model rather than heavy surveillance.

Public accountability comes through transparency (MP expenses are published, ministers’ schedules are public).

Benefits:

Encourages a culture of self-responsibility instead of policing.

Issues:

Critics say MPs still sometimes skip sessions without sufficient penalties.

Costs vs. Benefits: A general balance

Costs:

Hardware (scanners, servers, software).

Maintenance and IT support.

Risk of privacy and surveillance concerns.

Benefits:

Cuts absenteeism and ghost salary fraud.

Ensures fairness — everyone from MPs to minor staff follows the same rules.

Builds public trust by showing accountability.

Lessons from the three countries and conclusion

India demonstrates that biometric systems can significantly boost attendance, provided a robust IT infrastructure supports them. Malaysia illustrates both the advantages and the dangers of discouraging professionals. New Zealand offers an alternative: transparency and trust instead of biometric surveillance.

If Sri Lanka adopts this, it will improve accountability without fostering distrust and will build public trust by showing that accountability is essential. It’s a biometric time-tracking system aimed at fairness and accountability across different professions. This is important, so if someone opposes it, there is no factual basis for their objection.

(The writer served as the Special Adviser to the President of Namibia from 2006 to 2012 and was a Senior Consultant with the UNDP for 20 years. He was a Senior Economist with the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (1972-1993). He can be reached via [email protected].)