Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Thursday, 4 September 2025 00:41 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Samantha Kumarasena and Sanduni Thudugala

Ever wondered how much water it takes to produce a cotton shirt? Or what happens to your mobile phone after you throw it away? As conversations around climate change and sustainability intensify, more people from exporters to everyday consumers are beginning to look at the bigger picture. And in that picture, a tool called Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is taking centre stage.

Ever wondered how much water it takes to produce a cotton shirt? Or what happens to your mobile phone after you throw it away? As conversations around climate change and sustainability intensify, more people from exporters to everyday consumers are beginning to look at the bigger picture. And in that picture, a tool called Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is taking centre stage.

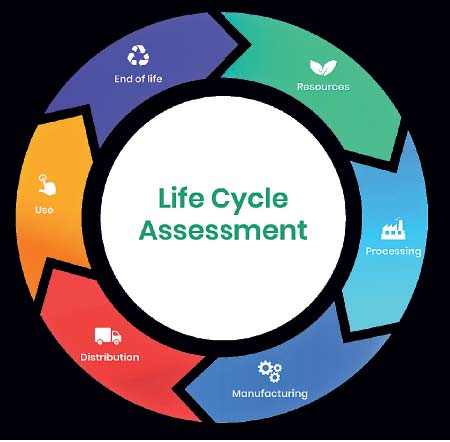

LCA is not new. Globally, it’s been used for decades to understand the environmental cost of products and services, not just during use, but throughout their entire journey: from raw material extraction to manufacturing, transportation, consumption, and final disposal. In other words, from cradle to grave.

Now, Sri Lanka is starting to explore how this concept, once confined to technical reports and research labs, can be applied in industries, classrooms, boardrooms, and even public conversations.

What is Life Cycle Assessment?

Life Cycle Assessment is a scientific method used to evaluate the full environmental footprint of a product or process. Unlike traditional environmental checks that focus on just one stage such as energy use during manufacturing, LCA considers everything: from raw material extraction to processing, distribution, use, and final disposal.

Take, for example, a cotton T-shirt. From the water used to grow the cotton, to the dyes used in processing, to global shipping and eventual disposal, every step in the supply chain has an environmental impact. LCA helps measure these impacts, identify “hotspots,” and guide decisions toward more sustainable alternatives.

It’s a method that brings science into sustainability and moves discussions from assumptions to evidence.

Why it matters now

With Sri Lankan exporters facing rising expectations from global buyers, especially in Europe, LCA is becoming more than a scientific tool. It’s fast becoming a passport to market access.

Across Europe and other regions, buyers are demanding transparency. They want to know how products are made, how much water and energy are used, what kind of packaging is involved, and what happens to waste. Crucially, they expect verified data, not just promises.

That’s where LCA becomes powerful. It enables companies to back their claims with credible evidence and to identify opportunities to improve operations while saving resources.

Local applications on the rise

Though still relatively new in Sri Lanka, LCA is gradually being explored in key sectors:

Tea plantations are using it to assess the impact of fertiliser, irrigation, and energy use during processing.

Textile factories are mapping emissions from dyeing and finishing stages to meet sustainability reporting requirements.

Construction firms are comparing material choices, such as clay vs. cement blocks, based on embodied carbon and durability.

Even tourism operators are exploring LCA to measure their energy consumption, waste generation, and food sourcing patterns.

What’s common across these examples is a shift from guesswork to insight. With this we no longer must rely on assumptions. With LCA, we can make data-driven decisions that benefit both the environment and our bottom line.”

Learning curve: Awareness still building

Despite its promise, LCA is not yet mainstream in Sri Lanka. Most businesses and even academic institutions are unfamiliar with how to conduct a life cycle assessment, what tools to use, or where to source reliable data.

Training remains limited. Popular software like SimaPro or GaBi can be expensive. And many open-access tools, such as OpenLCA, require guidance to use effectively. Adding to the challenge is a lack of localised data. Much of the available information is based on European or North American conditions, which don’t always reflect the realities of Sri Lankan supply chains, or waste streams.

Still, interest is growing. Short courses and professional workshops are beginning to introduce LCA fundamentals to students, engineers, and sustainability officers. And once people see how the method works, the response is often enthusiastic.

Key challenges

Despite this growing interest, several obstacles stand in the way of widespread adoption:

Lack of localised data: Without Sri Lanka-specific information on energy, transport, or materials, many assessments rely on foreign datasets that don’t reflect the local context.

Technical capacity: Many professionals have never heard of LCA, let alone used it. Integrating the topic into higher education and professional training is still a work in progress.

Cost and complexity: Full LCAs can be time-consuming and expensive. For small businesses, simplified approaches or sector-specific templates may be more practical.

Still, these are growing pains, not permanent roadblocks. Most experts agree that the long-term benefits far outweigh the initial challenges.

A tool for the future

Globally, LCA is being used to guide everything from green product design to carbon labelling to national policy decisions. Sri Lanka, too, has much to gain.

Imagine if infrastructure projects were evaluated not just by cost and time, but by long-term emissions and resource use. Imagine schools that teach students how everyday products impact the planet. Imagine businesses that compete not just on price, but on sustainability.

That’s the kind of thinking LCA enables. It’s not a silver bullet. But it’s a lens that helps us see what’s often hidden behind the labels and logos of daily life. You don’t need a science background to grasp the core message of LCA. It’s about paying attention to the entire journey of what we use.

A paper bag may seem more eco-friendly than plastic. But if the paper requires large amounts of water and energy to produce and is used only once, the benefit might be less than assumed. LCA helps clarify these trade-offs.

Sri Lanka is just beginning its journey with life cycle thinking. But with rising global expectations, growing environmental pressures, and a new generation of conscious consumers and professionals, the timing couldn’t be better.

Understanding the life cycle of our products isn’t just an academic exercise. It’s a practical, powerful way to build a smarter, cleaner, and more competitive Sri Lanka.

(Samantha Kumarasena is attached to Institute of Environmental Professionals Sri Lanka, National Cleaner production Centre, Sri Lanka and Sanduni Thudugala is attatched to National Cleaner production Centre, Sri Lanka.)