Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Friday, 3 October 2025 01:22 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Hambantota is Sri Lanka’s trump card

For Sri Lanka, the United States is more than just a trading partner. It is the single most important destination for Sri Lankan exports, particularly apparel, and a market that sustains hundreds of thousands of jobs and contributes significantly to national GDP. Yet, beneath this success story lies a structural imbalance. While Sri Lanka exports billions of dollars’ worth of goods to the United States each year, its imports from America remain comparatively small. This asymmetry leaves Sri Lanka exposed to tariff risks, particularly in the post-Trump era where US trade policy has become increasingly transactional.

For Sri Lanka, the United States is more than just a trading partner. It is the single most important destination for Sri Lankan exports, particularly apparel, and a market that sustains hundreds of thousands of jobs and contributes significantly to national GDP. Yet, beneath this success story lies a structural imbalance. While Sri Lanka exports billions of dollars’ worth of goods to the United States each year, its imports from America remain comparatively small. This asymmetry leaves Sri Lanka exposed to tariff risks, particularly in the post-Trump era where US trade policy has become increasingly transactional.

One potential path forward is to rethink how Sri Lanka engages with the US economy. By importing energy products—specifically crude oil, petroleum products, liquid natural gas (LNG) and liquefied petroleum gas (LPG)—Sri Lanka can simultaneously reduce its own energy costs, diversify away from its current Gulf-centric suppliers, and create a stronger bargaining position to negotiate tariff concessions for its exports. In other words, energy diplomacy can be the key to bridge the trade gap.

An unequal relationship

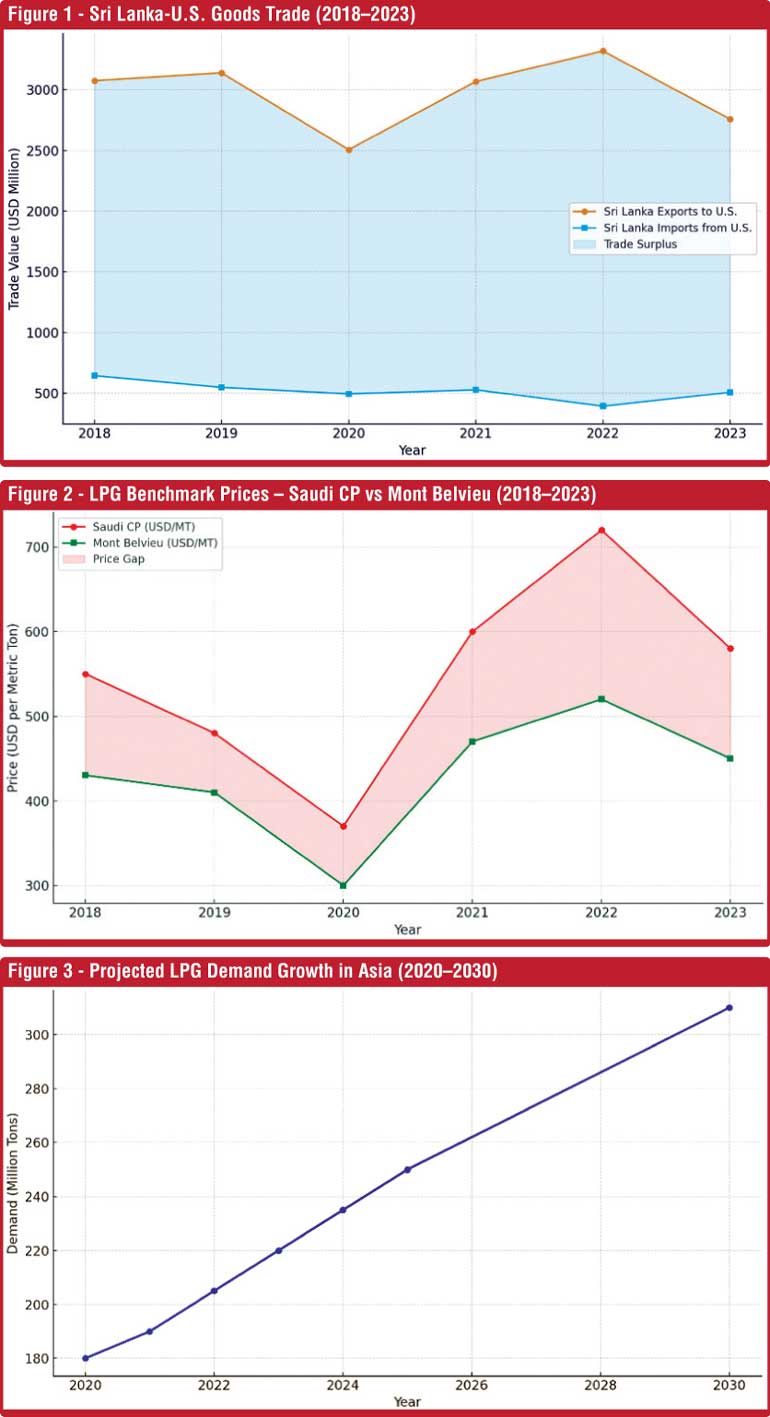

The trade statistics speak volumes. In 2023, Sri Lanka exported nearly $ 2.76 billion worth of goods to the United States, while imports from the US were just $ 507 million. This left Sri Lanka with a bilateral trade surplus of over $ 2.2 billion. The pattern is consistent over the past five years, with Sri Lanka exporting between $ 2.5–3.3 billion annually, while importing less than $ 650 million.

Figure 1 illustrates the persistent imbalance in Sri Lanka–US trade, highlighting both the scale of Sri Lanka’s export success and the absence of significant reciprocal imports.

Sri Lanka’s export basket to the US is dominated by apparel—outerwear, underwear, T-shirts, sportswear, and baby garments—while rubber tyres, gloves, tea, and seafood make up the remainder. By contrast, imports from the US are limited to animal feed, pharmaceuticals, plastics, electronics, and aviation parts. This asymmetry, while beneficial for Sri Lanka’s foreign exchange earnings, has become a political vulnerability under the doctrine of reciprocal tariffs.

The Trump doctrine and reciprocal tariffs

The Trump administration introduced a decisive shift in US trade policy. The philosophy of “reciprocity” meant that any country enjoying a large trade surplus with the US would be pressed to import more American goods or face tariffs. Steel and aluminum duties in 2018 set the tone, and Asian economies were particularly targeted.

India, Vietnam, and South Korea quickly adapted by importing US crude oil, LNG, and agricultural commodities, creating goodwill and securing tariff relief. For Sri Lanka, however, the risks remain acute because its reliance on the US market is not diversified across multiple sectors but is heavily concentrated in apparel. The initial US proposal to impose a 30% tariff on Sri Lankan exports exemplifies the urgency of finding a counterweight.

Competitiveness checkpoint: Where Sri Lanka stands on US tariffs versus rivals

Following further negotiation, the implemented rate on Sri Lanka has been revised to 20% (effective 7 August 2025). This aligns Sri Lanka with Vietnam and Pakistan (also at 20%) but keeps it disadvantaged against any countries that manage to negotiate exemptions or narrower product-line relief. India is presently at around 25%, (before it increased to 50%) and Bangladesh at 20% after its own talks.

The apparel sector has warned that under a 30% tariff scenario, exports to the US could fall by as much as 44%, a catastrophic decline for employment and GDP. Even at 20%, Sri Lanka’s competitiveness is fragile: if Washington does not grant further relief, buyers may divert orders to Vietnam or Pakistan. This highlights why Sri Lanka must negotiate proactively with Washington, using reciprocal concessions such as energy imports, to secure a durable advantage.

Sri Lanka’s rubber industry, once hailed as the global capital of industrial tyre manufacturing, earned its reputation by supplying world-class brands built on the country’s high-quality natural rubber. For decades, Sri Lankan factories exported solid and pneumatic industrial tyres to the US, which became the single largest destination market. However, the sector has faced mounting competition from low-cost producers in China and India, eroding its global market share. The recent imposition of a 20% US tariff on Sri Lankan exports adds a new layer of pressure, threatening margins and making Sri Lankan products less competitive against Asian rivals that can leverage economies of scale and cheaper raw material access. Unless mitigated through reciprocal trade concessions—such as expanded US energy imports from Sri Lanka—this tariff risk could accelerate the sector’s decline and undermine one of Sri Lanka’s most valuable industrial export legacies.

Comparative lessons from Asia: India, Vietnam, and Bangladesh

India provides a cautionary but instructive example. Facing US tariff threats in 2019, New Delhi sharply ramped up imports of US crude oil, which reached nearly 200,000 barrels per day at its peak. This helped defuse tensions and created a new channel for bilateral energy cooperation, even as India diversified its suppliers. While later controversies over Russia complicated this trajectory, the initial lesson was clear: US deficits can be reduced through energy purchases, softening tariff pressure.

Vietnam went further by combining tariff negotiations with structural reforms. Its commitment to import US agricultural and industrial products was tied to larger trade agreements. Today, Vietnam not only pays the same apparel tariff rate as Sri Lanka but has outcompeted it in market share due to scale, supply chain integration, and deliberate reciprocity.

Bangladesh, facing one of its toughest trade negotiations in 2024–25, ultimately leveraged its massive role as the second-largest garment supplier to the US to secure a lower tariff than initially announced. It offered phased increases in US cotton imports and other agricultural goods. The message for Colombo is clear: size matters, but strategy matters more.

Why energy imports from the US?

Sri Lanka is entirely dependent on imported energy. While LNG is another potential energy product that could be sourced from the United States, Sri Lanka is not yet ready for such imports due to the absence of the necessary infrastructure—a development that would take at least four to five years. In contrast, petroleum products and LPG present the fastest and most practical options to begin with. Petroleum products dominate, but LPG plays an increasingly critical role in households and industry.

Sri Lanka currently imports around 450,000 metric tons of LPG annually for domestic consumption, supplied through both state-owned Litro Gas and LAUGFS Gas. At a base rate of $ 650 per ton under Saudi CP, this represents an annual import value of $ 350–400 million. However, as prices frequently escalate to $ 750 per ton—and can reach $ 800 per ton once freight and premiums are added—the annual value rises closer to $ 430 million. Adding to this, LAUGFS exports an additional 36,000 metric tons of LPG from Hambantota to Bangladesh, bringing the combined trade value of Sri Lanka’s LPG imports and exports to over $ 500 million per year. This scale represents nearly a 100% increase on the value of current imports from the US and could be leveraged strongly in tariff negotiations with Washington.

Is US LPG cheaper than buying from the Middle East? The US, benchmarks LPG at Mont Belvieu, a hub reflecting shale production and domestic demand dynamics. Historically, Mont Belvieu prices have been 10–20% lower than Saudi CP, making them highly competitive even after accounting for longer shipping times.

Figure 2 compares Saudi CP and Mont Belvieu benchmarks, showing that US pricing offers a consistent discount that could benefit Sri Lanka.

Freight economics: US Gulf vs. Middle East to Hambantota

VLGC freight benchmarks illustrate the challenge and opportunity. As of August 2025, Baltic Exchange BLPG3 (US Gulf to Japan) was quoted at ~$138/mt, while BLPG1 (Middle East to Japan) was around $77/mt. Adjusting for distance, the estimated freight cost to Hambantota is about $118/mt from the US Gulf compared to just $31/mt from the Middle East—a gap of roughly $87/mt. Yet, even with this higher freight differential, the overall landed cost of US LPG—benefiting from Mont Belvieu’s lower base price—remains competitive against Middle Eastern supply.

To illustrate, take propane: Saudi CP currently trades around $ 520/mt for Gulf-Asia export contracts. Meanwhile, Mont Belvieu spot propane is well below that benchmark (reflecting US supply pressure). If one assumes Mont Belvieu propane is $350–$380/mt (a conservative estimate relative to Saudi CP) and adds the US freight cost of ~$118/mt, the landed cost from the US Gulf becomes ~$468–$498/mt. Against a Middle East landed cost from Saudi CP of ~$520/mt + only $31 freight = ~$551/mt, the US route still offers a $50–$80/mt advantage. That margin is strong enough to absorb terminal costs and handling fees—making US LPG imports viable even with longer distance.

Pricing translation to the household: What a 12.5 kg cylinder could save

Saudi CP propane was set at $520/mt in September 2025, while Mont Belvieu propane averaged about $352/mt. Even after adding a freight gap of around $87/mt and terminal/handling differentials of $30–60/mt, US cargoes still offer a net advantage of $22–52/mt over Middle East supply.

That saving translates into approximately Rs. 80–200 per 12.5 kg cylinder, assuming partial pass-through and USD/LKR ≈ 302. With current retail prices of Rs. 3,690 for a Litro 12.5 kg cylinder and about Rs. 4,100 for LAUGFS in Colombo, the potential relief for consumers is meaningful. For industry, it would also reduce input costs and enhance export competitiveness.

Public–private synergy for trade leverage

To realise this strategy, a public–private partnership (PPP) is essential. The Government must take the lead in negotiations with the US Trade Department, while Litro Gas and LAUGFS Gas coordinate infrastructure and volumes. While only LAUGFS currently has the infrastructure at Hambantota to import large parcels of LPG from the US, Litro’s position as the market leader provides the captive volume required—making the partnership mutually beneficial in every sense. Such collaboration would create the scale and credibility needed to leverage energy imports as a bargaining tool in tariff discussions.

Hambantota: From port to energy hub

Hambantota is Sri Lanka’s trump card. Sitting on the busiest East–West shipping lane and equipped to receive VLGCs, it offers a unique platform to not only import US LPG but also re-export it to nearby markets. Bangladesh, the Maldives, and even eastern India are constrained by shallow draft ports that cannot accommodate VLGCs. Hambantota could therefore serve as an entrepôt, storing large US cargoes and redistributing them to the region.

This transformation would turn Sri Lanka from a passive consumer into an active player in Asian energy logistics. In the long run, Hambantota could position itself as a trusted US partner for distributing energy into Asia at a time when India’s energy ties with Russia have strained its relationship with Washington.

Hambantota in the Indo-Pacific: More than an energy hub

From Washington’s perspective, Sri Lanka’s Hambantota port is not just a trade facility. In the US Indo-Pacific strategy, energy routes and logistics hubs are deeply intertwined with security, supply chain resilience, and competition with China. By aligning Hambantota with US energy flows, Sri Lanka could reposition itself as a strategic partner in the Indo-Pacific architecture, not merely a small export-driven economy.

This goes beyond tariffs. US policymakers are increasingly receptive to the idea that energy diplomacy can anchor political partnerships. If Hambantota is marketed not only as a commercial hub but as a regional energy security node, it could attract US attention and investment under Indo-Pacific initiatives, strengthening Sri Lanka’s leverage.

The rising Asian demand story

The strategic case is reinforced by demand projections. Asia already accounts for more than 42% of global LPG consumption, and demand is set to rise sharply as urbanisation, industrialisation, and household use expand.

Figure 3 shows a projection of LPG demand growth across Asia, with consumption expected to climb from 180 million tons in 2020 to over 300 million tons by 2030. This growth underscores the opportunity for Sri Lanka to use Hambantota as a platform for energy trade into the wider region.

Macro-economic implications for Sri Lanka

If tariffs remain at 20% while competitors negotiate down, Sri Lanka’s garment exports could lose up to $ 800 million annually, equivalent to roughly 1% of GDP. The apparel sector employs over 350,000 workers, meaning that even a modest contraction would trigger job losses in the tens of thousands. Foreign reserves, already stretched, would be hit by reduced export earnings.

By contrast, if Sri Lanka secures a modest tariff cut of even 5 percentage points (from 20% to 15%) through an energy-linked deal, the apparel sector could save $ 150–200 million per year in duty costs. Combined with the Rs. 80–200 per cylinder saving on LPG for households, the economic ripple effect would be significant: lower input costs, stronger consumer purchasing power, and more stable reserves.

A win–win proposition

The strategic and economic logic is clear. For the United States, Sri Lanka’s willingness to import crude oil, petroleum products, and LPG would help reduce the bilateral trade deficit, creating goodwill in Washington and giving Sri Lanka leverage in tariff negotiations. For Sri Lanka, US energy offers lower prices, diversification away from Middle East dependency, and the potential to turn Hambantota into a regional hub.

This is a win–win proposition. The US gains a new Asian market for its surging energy exports. Sri Lanka gains lower energy costs, stronger negotiating leverage on tariffs, and new opportunities in re-export logistics.

Action points for negotiators

To make this vision real, Sri Lanka should pursue four parallel actions. First, it must explicitly tie energy import commitments to tariff diplomacy, aiming to align or even undercut the 20% rate that currently applies to apparel exports. Second, it must guarantee transparent development of Hambantota as a regional hub, giving the US confidence in re-export potential. Third, it should negotiate pricing mechanisms linked to Mont Belvieu indices, with hedges to smooth volatility. Finally, policymakers must ensure that at least part of the saving is passed to households in the form of reduced LPG cylinder prices, building public support.

Energy as a tool of trade diplomacy

Sri Lanka cannot afford to take its US market access for granted. The Trump-era shift toward reciprocal tariffs has made it clear that surplus-exporting countries must find ways to balance the ledger. For Sri Lanka, energy imports from the United States offer the most practical and strategic solution.

By doing so, Sri Lanka would not only secure better terms for its apparel exports but also position Hambantota as a gateway for US energy into Asia, tapping into a regional demand surge that will define the next decade. This is more than an economic strategy; it is a diplomatic necessity, a way for Sri Lanka to transform its trade vulnerability into a platform for growth and resilience.

(The writer is the founder of LAUGFS Holdings Ltd., a diversified Sri Lankan conglomerate. With over 30 years of expertise in greenfield ventures across LPG, petroleum, lubricants, and power generation, he is recognised as one of the country’s most seasoned energy leaders. LAUGFS is also among the largest exporters of industrial rubber tyres from Sri Lanka to the United States, underscoring its longstanding and deep commercial ties with the US market.)