Tuesday Mar 03, 2026

Tuesday Mar 03, 2026

Friday, 31 July 2020 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

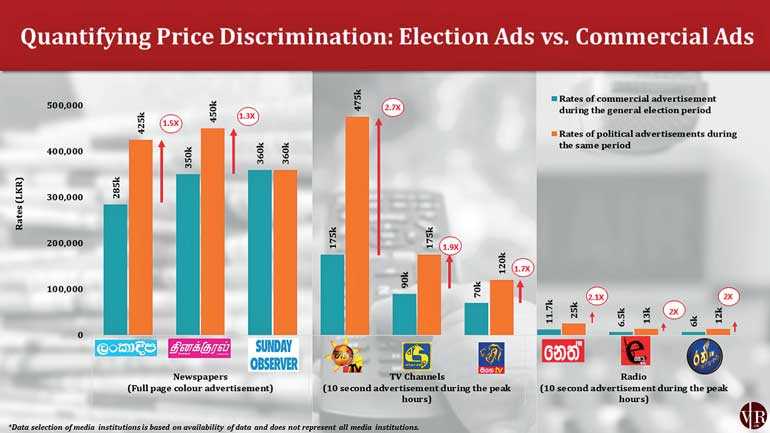

Graphic quantification of price discrimination in ads by the Sri Lankan media

This analysis suggests that charging higher rates for ads by parliamentary candidates is an exploitative measure rather than one driven by economic/business necessity.

A critical gap in these guidelines is that they do not require disclosure of rates, discounts and the resulting advertising revenue by media institutions from specific candidates and political parties during election periods.

This insight shows how the lack regulation in favour of democracy has allowed the Sri Lankan media to introduce a price discrimination system during elections, which exploits the democratic interests of the country, and of the parliamentary candidates.

As Sri Lanka heads towards the 2020 General Election, political advertising and promotion in the media is particularly critical for both the candidates and the voters. COVID-19 related campaigning restrictions adds to the need, for parliamentary candidates and voters, to connect and be informed through media.

The data analysed in this insight suggests that in the democratic process of communicating with the voter, candidates running for parliament are exploited and discriminated against by the Sri Lankan media.

Discrimination against parliamentary candidates

The present insight is based on an analysis of rate cards that are distributed by media stations to would-be advertisers and their agents.1 The pricing practice of the media appears to be similar to Sri Lankan hotels: where there is one room rate for foreigners and another room rate for locals – for the same rooms at the same time.

It turns out that media institutions in Sri Lanka also have one rate (with a discriminatory mark-up) for advertisements of parliamentary candidates and political parties, and another (normal) rate for all other types of advertisements. Both these rate cards are applied in parallel during election periods.

Exhibit 1 shows the differences in these two rates for a selected set of media stations of which the data was accessible. The data available for a set of newspapers shows that the discriminatory mark-up for the advertisements of parliamentary candidates could be as high as 50% (i.e. 1.5 times the normal price).

For the TV channels where the data was accessible, the discriminatory mark-up went up to 170% (i.e. 2.7 times the normal price). For the radio channels, there is data showing the discriminatory mark-up going up to 110% (i.e. 2.1 times the normal price).

This discrimination against parliamentary candidates, by the Sri Lankan media is not a practice that has commenced with the 2020 General Election. Verité Research has previously shared data and analysis of the same type of discrimination being practiced in the 2015 General Election as well.

Data on rate cards and pricing practices of the media is limited. A fuller analysis would be possible if such data were more publicly and openly accessible.

Democratic and economic logic supports the reverse

The democratic process requires candidates and political parties to campaign effectively and meaningfully disseminate information about their qualifications, their policies, and their ballot numbers.

This requires access to media – which is expensive. Therefore, the needs of a democratic society are better served if the discrimination was in the opposite direction- with parliamentary candidates receiving subsidised rates, instead of penal rates, for their ads in the media.

There is also an economic and egalitarian case for providing lower rates for political advertising, instead of the higher rates being charged. It is the same economic case that leads inter-city buses to take-in additional “bonus” passengers going shorter distances at reduced rates. The cost infrastructure of media is met by the regular flow of commercial advertising – which is therefore priced to ensure, at least, full cost recovery.

Elections occur infrequently and the excess demand for political ads during election periods does not come with a concomitant increase in costs. Therefore, even by charging the normal rates, media stations would make higher overall profits from the extra demand for placing ads during elections. Consequently, even offering a reduced rate for these “bonus” political ads would still enable media institutions to maintain their normal profitability. This analysis suggests that charging higher rates for ads by parliamentary candidates is an exploitative measure rather than one driven by economic/business necessity.

The media is not regulated in favour of democracy

Broadcast frequencies/airwaves which are used by the media are regarded as public property.2 It is a principle in law that all public property must be held and used in trust for the benefit of the general  public, regardless of whether the property is held/used by State or private institutions.3 Accordingly, any media station that enjoys the privilege of using public frequencies/airwaves are ‘subject to a correspondingly greater obligation to be sensitive to the rights and interests of the public’.4

public, regardless of whether the property is held/used by State or private institutions.3 Accordingly, any media station that enjoys the privilege of using public frequencies/airwaves are ‘subject to a correspondingly greater obligation to be sensitive to the rights and interests of the public’.4

This principle is recognised in Article 28 of the Constitution which states that all persons (individuals and corporate bodies) have a “fundamental duty” to uphold the Constitution, respect the rights and freedoms of others, and to protect and preserve public property. Therefore, a further obligation towards the general public is cast on private media stations by Article 28.

Since these ads are one of the most common methods used by parliamentary candidates to communicate with voters, the exploitative pricing practice could be undermining the legally protected right of both voters and politicians ‘to participate in public affairs’, as set out in the International

Covenant on Civil and Political Rights Act No.56 of 2007.5

Despite these obligations and duties cast on media stations, there is no specific law/regulation enacted in Sri Lanka which governs the pricing and enforces transparency of political ads during election periods. Consequently, democratic interests are vulnerable to being flouted, instead of being supported, by the media.

The interests of democracy are flouted by discriminatory pricing

Based on the present analysis, two areas emerge in which the interests of democracy can be flouted. Firstly, as shown in Exhibit 1, the democratic process is openly exploited by the imposition of a higher price, on the category of political communication/advertising during the election period.

Secondly, under the current framework, media stations can engage in another level of discrimination as well. Any media station can, without disclosure and at its discretion, offer discounts on these exploitative rates to selected candidates – thus providing them an unfair advantage over candidates that don’t receive the same discounts.

Therefore, in addition to the practice of category level discrimination between political ads and other types of ads, the media can also engage in candidate level discrimination between the parliamentary candidates who are placing the ads.

That means certain parliamentary candidates can face not only discriminatory barriers to their ads in relation to other types of ads, but may also face price discrimination in relation to their fellow competitors in the election – undermining their constitutional right to equal treatment and non-discrimination amongst competing candidates as well.

The Election Commission and gaps in media regulation

Through the 19th Amendment to the Constitution, the Election Commission of Sri Lanka (‘ECSL’) is authorised to issue guidelines to ‘any broadcasting or telecasting operator or any proprietor or publisher of a newspaper… to ensure a free and fair election’.6

On 3 June, the ECSL published guidelines which are required to be followed by all media institutions in their coverage during election periods.7 These guidelines state, among other things, that:

“All telecasting, broadcasting and print media shall be neutral and impartial in their reporting of matters relating to an election, and shall not act in a manner which discriminates against any contesting political party, independent group or candidate or confers a special benefit to any such party, group or candidate, in allocating airtime on radio or television and allotting space in the newspapers for such political party, independent group or candidate.”

These guidelines do not address the category level discrimination highlighted by the data. They do, however, address the candidate level discrimination that is facilitated by the category level discrimination; as they prohibit conferring of special benefits to candidates or parties in the allocation of airtime or newsprint space by the media.8

Guidelines requiring disclosure can be a first step solution

Although the ECSL issues guidelines to promote ethical media practices, the lack of enforcement mechanisms is a common theme of the guidelines, rendering them rather inconsequential. Even the guidelines for the 2019 Presidential Election, which addressed candidate level discrimination, lacked a mechanism for enforcement.9

Furthermore, despite the far-reaching consequences of such discrimination, the ECSL also has insufficient power to take legal action against private media institutions.10 Thus, private media institutions have additional space to flout these guidelines.

Apart from the difficult of enforcement, a critical gap in these guidelines is that they do not require disclosure of rates, discounts and the resulting advertising revenue by media institutions from specific candidates and political parties during election periods.

Due to concerns about the abuse of advertising space, international social media platforms (such as Facebook) now make such data available, while mainstream media in Sri Lanka maintains opacity, which is supported by the lack of guidelines and regulations.

This insight shows how the lack regulation in favour of democracy has allowed the Sri Lankan media to introduce a price discrimination system during elections, which exploits the democratic interests of the country, and of the parliamentary candidates.

Verité Research is an independent think-tank based in Colombo that provides strategic analysis to high-level decision-makers in economics, law, politics and media. Comments are welcome. Email [email protected]

Footnotes

1. Sunday Observer - General Election 2020 Rates published by ANCL and Casual Advertising Rates published by ANCL on June 15, 2019; Thinakkural -General Election and Commercial Rate cards published by Asian Media Publications (PVt) Ltd. on March 01, 2020; Sunday Lankadeepa - Advertising Rates published by Wijeya Newspapers Limited on 01.03.2019; Hiru TV - General Elections Rate card published by Hiru TV on May 29 2020 and the Commercial Rate card published on July 8, 2020; Swarnawahini - General election 2020 Rate cards and the commercial rate cards published by Swarnawahini on June 30,2020; Siyatha TV - General election 2020 Rate cards and the commercial rate cards published by Siyatha TV; E FM - General election 2020 Rate card and the commercial rate for 2020 published by E FM; Neth FM - General election 2020 Rate cards and the commercial rate cards published by Swarnawahini on April 1, 2018; Ran FM - General election 2020 Rate cards and the commercial rate cards published by Ran FM.

2. Fernando v. Sri Lanka Broadcasting Corporation & Others [1996] 1 Sri.L.R 157, p. 172.

3. See Bulankulama and Others v. Secretary, Ministry of Industrial Development and Others (Eppawela Case) (2000) 3 Sri LR 243, Sugathapala Mendis v. Chandrika Kumaratunga & Others [2008] 2 Sri.L.R. 339 and Environmental Foundation Limited v. Mahaweli Authority of Sri Lanka and Others [2010] 1 Sri.L.R. 1.

4. Fernando v. Sri Lanka Broadcasting Corporation & Others [1996] 1 Sri.L.R 157, p. 172.

5.Section 6, International Convention on Civil and Political Right Act No. 56 of 2007.

6. Article 104B 5)(a), The Sri Lankan Constitution 1978.

7.Extraordinary Gazette, No. 2178/24 issued on 03 June 2020, at http://elections.gov.lk/web/wp-content/uploads/publication/ext-gz/2178_24_E.pdf [last accessed on 23 July 2020].

8.ibid, Guideline No. 2 and Guideline No. 11.

9.Verité Research, Briefing Note: Powers of the Election Commission to Regulate Privately-Owned Media during Elections in Sri Lanka (November 2019), at https://www.veriteresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Powers_of_the_Election_Commission_to_Regulate_Privately_Owned_Media.pdf [last accessed 23 July 2020], p.3.

10. PAFFREL, Interim Report on the Presidential Election – 2019, at http://www.paffrel.com/posters/191227131223Interim%20report%20of%20Presidential%20Election%202019.pdf [last accessed on 23 July 2020], p.2. See also Article 104GG, The Sri Lankan Constitution, which only imposes penalties for non-cooperation/non-compliance with the ECSL by public officers.