Thursday Mar 12, 2026

Thursday Mar 12, 2026

Wednesday, 31 December 2025 00:20 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Cyclone Ditwah, which recently swept across Sri Lanka, has resulted in the tragic loss of nearly 640 lives. Over 200 individuals remain missing, and over 2.3 million people have been affected. Comprehensive data on damage to livestock and property is still being compiled.

Cyclone Ditwah, which recently swept across Sri Lanka, has resulted in the tragic loss of nearly 640 lives. Over 200 individuals remain missing, and over 2.3 million people have been affected. Comprehensive data on damage to livestock and property is still being compiled.

According to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), flooding has impacted roughly 20 per cent of Sri Lanka’s land area, an estimated 1.1 million hectares. Initial assessments place the economic loss between $ 6 and 7 billion, though this figure is expected to rise considerably. Economic analysts caution that Cyclone Ditwah may significantly disrupt the country’s ongoing efforts toward economic recovery.

The purpose of this article is not to address unverified claims suggesting that the cyclone could have been predicted with greater accuracy. Instead, it aims to reflect on our collective civic responsibilities during a national disaster of this scale and to consider the measures necessary to minimise future loss of life and property.

Three types of disaster

Disasters are generally categorised into three types:

Cyclone Ditwah is classified as a natural disaster. Effective management of such events requires action across several key stages: preparedness, emergency response, and post-disaster recovery and reconstruction. Following the 26 December 2004 tsunami, Sri Lanka enacted the Disaster Management Act No. 13 of 2005, establishing the legal framework for disaster governance. Under this Act, the National Council for Disaster Management (NCDM) was created as the apex body, supported by the Disaster Management Centre (DMC), which is responsible for policy implementation and operational coordination.

Reports indicate that the NCDM convened in August 2025 for the first time in seven years. This raises important questions not only about whether relevant institutions and authorities fulfilled their responsibilities in preventing or mitigating such extensive loss of life and property, but also about the role we, as citizens, played or neglected to play.

As a society, we often assume that disasters will not affect us personally. In Sri Lanka, and across much of South Asia, there is generally limited public engagement with weather forecasts, climate trends, and official warnings, except among communities directly dependent on agriculture. In light of the devastation caused by Cyclone Ditwah, it is essential to critically evaluate how all key stakeholders, including the Department of Meteorology, the Department of Irrigation, the National Building Research Organisation, the Disaster Management Centre, the Government, the media, and the public—acted individually and collectively to mitigate the impact of this disaster.

Meteorological Department accountability and public responsibility

The Department of Meteorology is the legally mandated authority in Sri Lanka responsible for issuing weather information and early warning advisories. Despite operating with limited human and technological resources, the Department consistently issues weather bulletins approximately three times a day, increasing the frequency during high‑risk or rapidly evolving situations.

On 12 December 2025, the Sri Lanka Association of Meteorologists (SLAM) released a detailed media statement explaining the development of the low‑pressure system that later intensified into Cyclone Ditwah, as well as the scientific limitations inherent in forecasting such events. Similarly, the Minister of Health and Mass Media, Dr Nalinda Jayatissa, provided a clear explanation during the Cabinet media briefing on 11 December 2025.

These clarifications became necessary following a news report aired by a private television channel. The news report claimed that during an interview on 12 November the Director General of Meteorology had stated that Cyclone Ditwah, which made landfall on 27 November, had been known of well in advance. Edited excerpts of this interview were broadcast on 28 and 29 November, causing the claim to spread rapidly across social media. Certain opposition Members of Parliament and other political actors further amplified this narrative. Additional allegations circulated that the India Meteorological Department (IMD) and the BBC had predicted rainfall exceeding 500 mm as early as 12 November. A considerable portion of the public was misled by these assertions.

These clarifications became necessary following a news report aired by a private television channel. The news report claimed that during an interview on 12 November the Director General of Meteorology had stated that Cyclone Ditwah, which made landfall on 27 November, had been known of well in advance. Edited excerpts of this interview were broadcast on 28 and 29 November, causing the claim to spread rapidly across social media. Certain opposition Members of Parliament and other political actors further amplified this narrative. Additional allegations circulated that the India Meteorological Department (IMD) and the BBC had predicted rainfall exceeding 500 mm as early as 12 November. A considerable portion of the public was misled by these assertions.

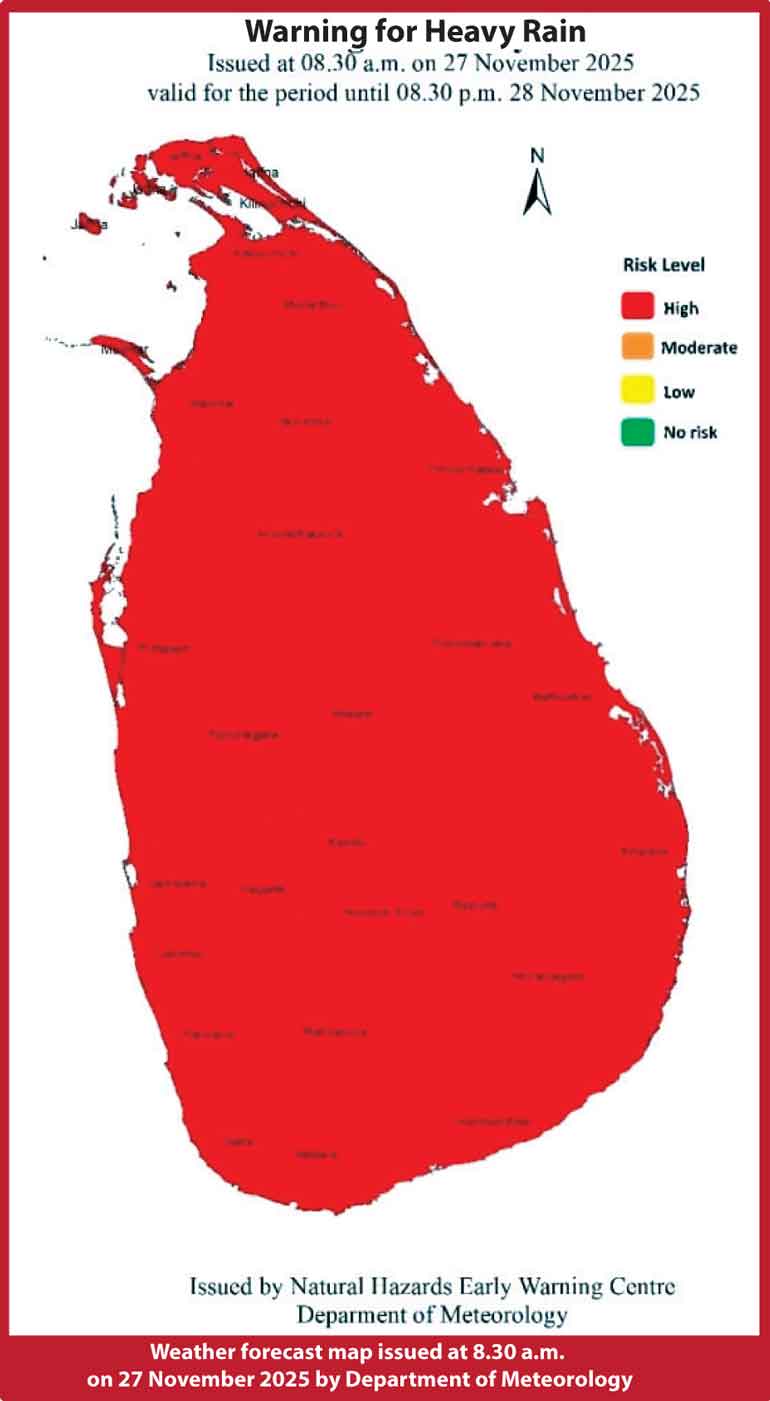

From 25 November onwards, both electronic and print media consistently reported that the system was intensifying. The Department of Meteorology had formally notified its key stakeholders, including the Department of Irrigation, the National Building Research Organisation (NBRO), and the Disaster Management Centre (DMC), a fact confirmed by the Director of Water Management of the Department of Irrigation. By the afternoon of 27 November, the system had been officially named Ditwah, and Government authorities had already begun evacuating communities in river basins and areas near reservoirs and tanks. The NBRO issued red alerts for landslide risk across numerous Divisional Secretariat divisions. The Department of Meteorology also warned that certain districts could receive rainfall exceeding 200 mm and 150 mm, and its 8.30 a.m. bulletin on 27 November placed the entire country on a red alert. However, because the cyclone remained over land for an extended period, actual rainfall far exceeded initial projections.

Doppler radar systems are typically used to track cyclone paths and estimate rainfall intensity. Sri Lanka does not currently possess such a system. Instead, the Department relies on numerical weather prediction (NWP) models (down-scaled versions of global models), which have inherent limitations. For context, on 4 July 2025, Tropical Storm Barry caused severe flash flooding in Texas despite the United States having some of the world’s most advanced meteorological technology resulting in approximately 135 fatalities. In that instance, opposition parties did not blame the Government, nor did the media accuse the U.S. National Weather Service of having predicted the event months earlier. There were no political campaigns targeting the administration of President Donald Trump, nor attempts to initiate litigation before the U.S. Supreme Court.

What merits the highest commendation, however, is the extraordinary response of Sri Lanka’s armed forces who reached disaster sites within hours to rescue individuals trapped beneath landslides. Equally admirable were the countless citizens who stepped forward to assist. Volunteer groups, socially responsible media institutions, and young social media activists mobilised within hours to deliver food and essential supplies to hundreds of thousands of displaced persons. The Government, led by the President, acted swiftly by appointing a Commissioner General for Essential Services and Emergencies.

Clarifying misleading reports

Regrettably, neither the Director General of Meteorology nor the private television channel responsible for the misleading report have issued a correction. If inaccurate information was broadcast, the Director General, as a senior public official, had a duty to clarify the matter immediately. Instead, during the disaster period, he reportedly told a State‑owned newspaper that he possessed superior meteorological knowledge. If he had indeed known on 12 November about a cyclone that made landfall on 27 November, he would be considered among the world’s most exceptional meteorologists. His primary responsibility, however, would have been to alert the relevant disaster management authorities, not to make statements on a private television channel. In the absence of such action, a reasonable observer could conclude that he was knowingly or unknowingly used by the said channel.

Regrettably, neither the Director General of Meteorology nor the private television channel responsible for the misleading report have issued a correction. If inaccurate information was broadcast, the Director General, as a senior public official, had a duty to clarify the matter immediately. Instead, during the disaster period, he reportedly told a State‑owned newspaper that he possessed superior meteorological knowledge. If he had indeed known on 12 November about a cyclone that made landfall on 27 November, he would be considered among the world’s most exceptional meteorologists. His primary responsibility, however, would have been to alert the relevant disaster management authorities, not to make statements on a private television channel. In the absence of such action, a reasonable observer could conclude that he was knowingly or unknowingly used by the said channel.

The Government must therefore urgently question both the television channel and the Director General of Meteorology regarding the dissemination of misleading information and the failure to issue corrections. Allowing such conduct to go unaddressed would set a dangerous precedent. An independent investigation should be initiated without delay, as the episode borders on a coordinated attempt to mislead the public. From a professional standpoint, it is also necessary to examine whether the Director General possessed the required meteorological expertise and whether he met the qualifications stipulated under the Sri Lanka Scientific Service Minutes at the time of his appointment. This review may include consultations with former officials of the Sri Lanka Scientific Service Board and members of the relevant interview panels.

Swift emergency relief

In the aftermath of the disaster, emergency relief arrived swiftly from neighbouring countries including India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, the Maldives, Bhutan, and Nepal as well as from Japan, the United States, China, the United Arab Emirates, France, the European Union, and Russia. International organisations such as the United Nations Development Program, the World Bank, and the Asian Development Bank, along with foreign citizens and Sri Lankans living overseas, contributed generously with financial and material aid. Local religious institutions, including the Temple of the Sacred Tooth Relic and the Gangaramaya Temple, played a significant humanitarian role. Media reports highlighted a Buddhist monk from Gokarella who donated approximately 20 acres of temple land for relief and resettlement. Prominent business leaders also provided essential supplies to affected communities.

Former President Chandrika Kumaratunga donated Rs. 250 million from the Bandaranaike Foundation to the official Government relief fund, strengthening public confidence in the State‑managed effort. In stark contrast, an individual claiming to be a Buddhist monk publicly urged citizens not to contribute to the Government fund. At a time of national crisis, it is important for well‑meaning Buddhists who follow such figures to reflect seriously on the implications of such statements.

Former President Chandrika Kumaratunga donated Rs. 250 million from the Bandaranaike Foundation to the official Government relief fund, strengthening public confidence in the State‑managed effort. In stark contrast, an individual claiming to be a Buddhist monk publicly urged citizens not to contribute to the Government fund. At a time of national crisis, it is important for well‑meaning Buddhists who follow such figures to reflect seriously on the implications of such statements.

Despite political differences, Opposition representatives at both local and national levels were seen working alongside Government officials to support affected communities, an encouraging demonstration of collective responsibility during a moment of profound national hardship.

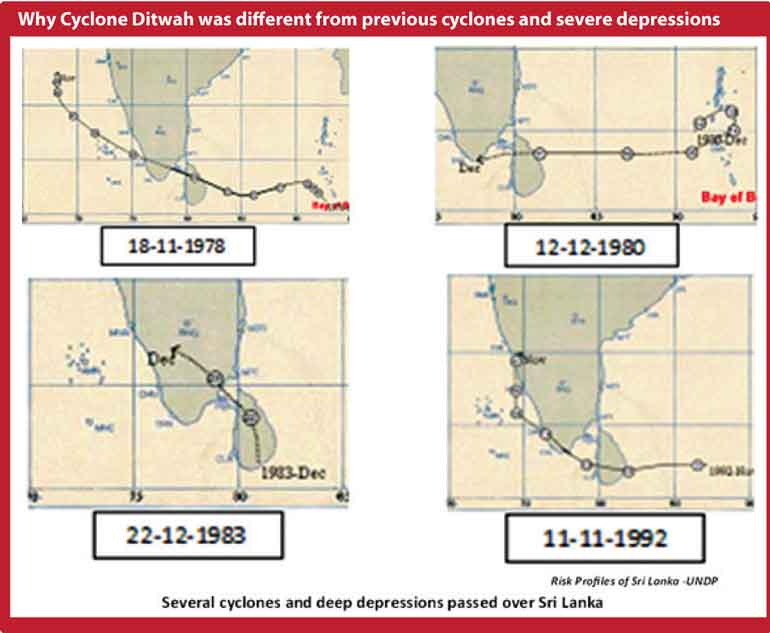

Why Cyclone Ditwah was different from previous cyclones and severe depressions

Cyclone Ditwah differed markedly from previous cyclones and severe low‑pressure systems that have affected Sri Lanka, primarily due to its unusually slow movement and prolonged presence over the island. Unlike earlier systems, Ditwah advanced at a very slow pace and remained over land for an extended period. As it travelled northward parallel to the coastline, it retained a high concentration of atmospheric moisture, producing exceptionally intense rainfall. The resulting precipitation far exceeded forecast expectations.

In several areas, rainfall between 350 mm and 500 mm was recorded within a single day. This extraordinary volume triggered severe landslides in the hill country, accounting for approximately 90 per cent of the reported fatalities. While previous cyclones typically affected limited regions, Ditwah caused widespread and severe impacts across a much larger geographical area. These characteristics were clearly highlighted by the Sri Lanka Association of Meteorologists (SLAM) and several recognised experts in meteorology and ocean sciences.

Despite repeated warnings from the Police, relevant authorities, and electronic media urging residents to evacuate high‑risk homes and areas, some individuals disregarded these advisories. This contributed to the rising death toll. In several districts, delayed evacuation resulted in tragic circumstances in which members of the armed forces lost their lives while attempting rescue operations.

The roles of the Department of Irrigation, NBRO, and the Disaster Management Centre during an emergency

Department of Irrigation

Using rainfall forecasts and advisories issued by the Department of Meteorology, the Department of Irrigation manages reservoir operations based on data from automated and manual rain gauges, catchment‑area rainfall stations, water‑level gauges, specialised software, and the professional expertise of irrigation engineers. Decisions to open spill gates, whether automatically or manually are made individually for each reservoir, taking into account inflows, storage capacity, and downstream safety.

During Cyclone Ditwah, reservoir operations were carried out strictly in accordance with meteorological information. For major hydropower reservoirs such as Kotmale, spillway operations were coordinated with electricity generation requirements. Nevertheless, certain opposition groups used media platforms to spread false and alarmist claims regarding reservoir operations, causing unnecessary public fear. These allegations warrant investigation once the emergency phase concludes.

Water management is a highly technical process grounded in scientific data, reservoir capacity, and the structural integrity of dam embankments. It cannot be dictated by political authority. Arbitrarily emptying reservoirs would create severe secondary crises, including drinking water shortages, agricultural disruption, and reduced hydropower generation.

During Cyclone Burevi in November 2020, despite advance warnings, anticipated rainfall did not materialise. Even then, the Department of Irrigation exercised caution and avoided unnecessary spillway releases. Reservoir operations are conducted in close coordination with local farming communities and residents. However, sedimentation has significantly reduced the storage capacity of many reservoirs, and unauthorised construction near reservoir reservations and tank bunds has placed lives at serious risk. These issues demand renewed public attention.

(The author is a Chartered Electrical Engineer and a member of the Institution of Engineering and Technology (UK), with postgraduate qualifications in Electronics Engineering and Satellite Communication. He has led a World Bank–funded, ADPC-administered project on climate-resilient urban and peri-urban farming in Sri Lanka. A freelance consultant in lightning protection, he serves as a Technical Advisory Member at the Arthur C. Clarke Institute for Modern Technologies, is an Executive Committee Member of the South Asian Lightning Network (SALNET), and has chaired national standards committees on lightning protection)