Sunday Feb 01, 2026

Sunday Feb 01, 2026

Friday, 6 June 2025 00:20 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Across South Asia, the pandemic exposed not only the fragility of livelihoods, but also the limits of systems designed to protect them. As informal workers scrambled to stay afloat, governments rushed to deploy cash transfers at scale. Yet speed alone was never the whole story. What mattered just as much—if not more—was whether people trusted the system enough to register, to show up, to believe that help would come.

Across South Asia, the pandemic exposed not only the fragility of livelihoods, but also the limits of systems designed to protect them. As informal workers scrambled to stay afloat, governments rushed to deploy cash transfers at scale. Yet speed alone was never the whole story. What mattered just as much—if not more—was whether people trusted the system enough to register, to show up, to believe that help would come.

In Sri Lanka, as in much of the region, that trust has been hard-earned, sometimes uneven, and always political. And yet, the past few years have also revealed something quietly powerful: a growing recognition that resilience is not just about how much you give, but how you build.

Financial inclusion in Sri Lanka is not just about bringing people into the banking system—it’s about understanding how low-income communities already manage their financial lives, and redesigning products around those realities. In recent engagements across the island—including consultations in post-conflict districts and the estate sector—I’ve observed how overextended, under-protected households rely on informal financial tools out of necessity, not choice. This reality is deeply gendered and regionally uneven in Sri Lanka, especially in the estate sector and the Northern and Eastern provinces, where histories of marginalisation, conflict, and neglect shape how people—especially women—engage with money.

The gendered nature of financial exclusion

Despite strong gains in human development, only about one in three working-age women in Sri Lanka participate in the labour force—significantly lower than male participation and among the widest gender gaps in South Asia. While bank account ownership has risen—driven in part by government-to-person (G2P) payments like Aswesuma—usage remains low. Even when women hold bank accounts, they may not control the money, trust the system, or find it flexible enough to manage their daily survival.

The poor—especially women—don’t need a single product. They need a mix of tools for saving, borrowing, and insuring against shocks. In Sri Lanka, informal rotating savings groups (seettu), jewellery pawning, and neighbourly credit still outcompete banks in responsiveness and trust. Formal services often don’t cater to their rhythm of life: small, frequent cash flows and sudden emergencies.

Estate sector: Banking without belonging

In the tea plantations, where Tamil estate workers live in isolated, legacy labour settlements, formal financial inclusion remains shallow. Many households have accounts due to welfare transfers, but meaningful use is low. The main issues are documentation gaps, citizenship ambiguities, and generational poverty. Estate women often rely on informal mechanisms—borrowing from supervisors or pooling income in kin networks—not because they distrust money, but because formal institutions haven’t earned their trust.

Reliability and flexibility matter more than interest rates. Estate women need micro-loans without bureaucratic hurdles, savings options that don’t penalise early withdrawals, and financial services in their language and locality. These are not just policy gaps; they are upstream design challenges. Financial services in these regions must be adapted to fragmented incomes, legacy documentation issues, and low formal literacy. Embedding contextual diagnostics and community consultations at the outset of project design would dramatically improve uptake and retention.

Recent housing and infrastructure investments (like the Indian-aided estate housing projects) are steps forward—but they must be paired with embedded financial education, mobile access, and gender-sensitive service delivery.

North and East: Post-war, still precarious

The war may have ended in 2009, but financial scars persist. Many households, especially female-headed ones, still rely on remittances, informal credit, or barter economies. In conflict-affected regions, households aren’t waiting for charity—they’re innovating constantly to make ends meet. What they need is a system that meets them where they are.

Post-conflict microfinance has often failed here—either too predatory, or too formalised to feel accessible. Programs that have worked best involved local trust-based intermediaries and integrated livelihood support, like village banking or group-based savings-and-loans. Digital innovations (like mobile wallets and GovPay) offer promise—but only if backed by agent networks and digital literacy efforts targeting women.

Social protection as financial on-ramp—or missed opportunity?

Programs like Aswesuma can be powerful tools for financial inclusion. By requiring bank accounts, they formalise millions of lives. But if beneficiaries cash out immediately, the account is a hollow shell. The next step is to transform the payment platform into a financial platform—with optional savings, insurance, and accessible credit built in.

What’s missing now is intentional design: simple mobile interfaces in Tamil and Sinhala, opt-in nudges to save a portion of transfers, and grievance redressal mechanisms that women can access confidently. Pairing transfers with financial capability workshops—run by trusted local actors—could help transform one-time transactions into long-term relationships.

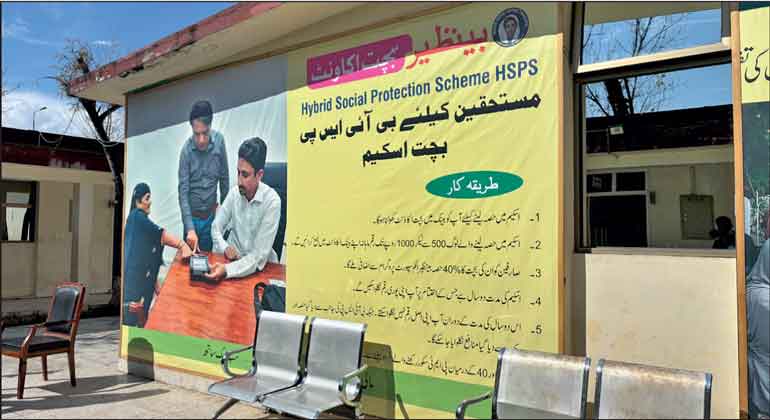

Learning from others: Pakistan’s hybrid model

A compelling example comes from Pakistan’s Crisis-Resilient Social Protection (CRISP) program, which combines traditional cash transfers with incentives for savings. This hybrid approach encourages informal workers—particularly women—to build buffers against future economic shocks. By integrating this mechanism with existing programs and layering in components for health, education, and nutrition, CRISP reflects a more holistic and sustainable approach to poverty alleviation.

In February 2025, I visited a BISP service delivery window in Islamabad and met with several women beneficiaries of Pakistan’s hybrid social protection savings program (HSPS). These women were using predictable digital transfers to plan for real futures—starting micro-enterprises, covering education costs, or saving for life events. The BISP model didn’t just deliver cash; it delivered agency. Through integrated financial literacy, participants were taught how their savings could grow, compound, and unlock opportunity.

This visit reaffirmed something I’ve seen across South Asia: resilience isn’t built through one-off transfers, but through layered, gender-sensitive systems that offer women a financial roadmap. Such diagnostic insights—combined with project design, stakeholder engagement, and follow-through—are central to effective upstream and advisory work.

Sri Lanka could adopt similar thinking: rather than treating cash transfers as isolated payments, future iterations of Aswesuma could encourage savings behaviour, offer access to micro-insurance, and allow participants to channel a portion of their benefits into long-term resilience. Embedding a hybrid model in Sri Lanka’s social protection framework would not only deepen financial inclusion—it could build the adaptive capacity of vulnerable communities in the face of future crises.

What has worked—and why it matters

Across Sri Lanka, certain approaches have worked:

These successes weren’t just financial—they were social. They acknowledged that for the poor, money is rarely just money—it’s identity, dignity, power, and survival.

A way forward: Designing for real lives

Financial inclusion must move beyond counting accounts. It must reflect the financial lives of the poor as they actually are—messy, adaptive, relational. For Sri Lanka’s women, especially in its most vulnerable regions, this means:

As South Asia navigates the next phase of recovery and resilience, financial inclusion must evolve from a numbers game into a systems-building agenda. The tools exist—digital payments, conditional transfers, impact-linked savings, MSME lending. But success lies in how they’re sequenced, targeted, and delivered.

Fieldwork across Nuwara Eliya and the conflict-affected North and East reveals a common truth: inclusive finance succeeds not through scale alone, but when design meets the lived dignity of those it aims to serve. With the right advisory engagement—one grounded in fieldwork, backed by analytics, and aligned with market creation goals—Sri Lanka can move closer to a financial ecosystem that serves everyone.

(The writer is a public policy specialist and development practitioner with a decade of experience in government and international development institutions across South and East Asia. Her work spans social protection, financial inclusion, governance reform, and institutional development, with a special focus on inclusive finance and adaptive social protection systems.)