Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Thursday, 9 October 2025 04:08 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

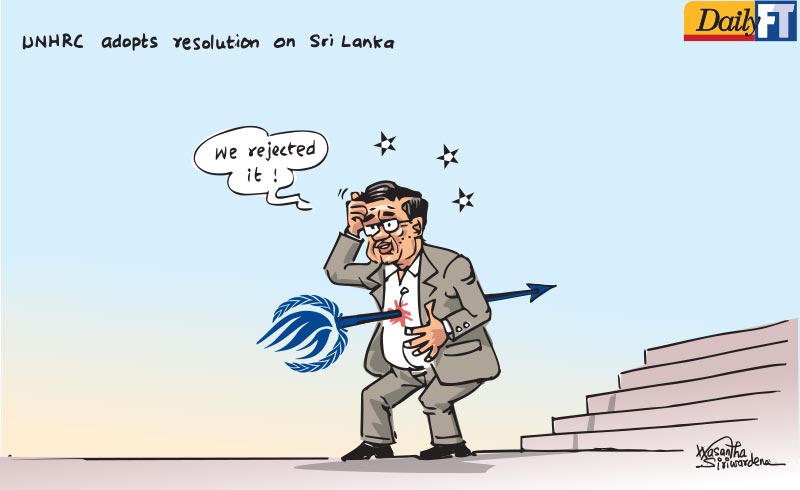

The latest Human Rights Council Resolution on Sri Lanka (60/L-1/Rev-1) was adopted without a vote in Geneva on the 6th of October 2025, despite Sri Lanka’s strongly stated rejection of it. What happened there and why was it adopted “without a vote”?

The latest Human Rights Council Resolution on Sri Lanka (60/L-1/Rev-1) was adopted without a vote in Geneva on the 6th of October 2025, despite Sri Lanka’s strongly stated rejection of it. What happened there and why was it adopted “without a vote”?

At its simplest, it was adopted that way because a call for a vote on the resolution was consciously passed up by Sri Lanka, which could have requested a member state such as China, to call for it.

Immediately after Sri Lanka’s Permanent Representatives at the UN in Geneva, Himali Arunatilleka’s speech rejecting the Resolution, the Chair of the UNHRC asked the Council if anybody would like to call for a vote on the Resolution, since there was clearly a difference of opinion on it, including those of China and Cuba which had disassociated themselves from what was seemingly a consensus on the Resolution earlier.

Despite the rejection of the resolution by Sri Lanka, there was deadly silence in the Council. The Chair then gavelled it through as adopted without a vote, indicating no serious objections by any country to its formal adoption. Clearly, Sri Lanka had not arranged for a friendly member country to call for a vote on its behalf.

This decision not to call for a vote, deliberately taken by Sri Lanka, presumably had some logic. One was articulated on TV the next day by a government representative, who explained that there was nothing the UNHRC could do to us, so we didn’t bother with a vote. Could the government then explain why the Foreign Minister, who didn’t go to some important international summits such as the BRICS and SCO, actually made the effort to fly to Geneva and speak there on this Resolution?

There could be far more credible reasons for this decision than this possible cover-up. The last time Sri Lanka called for a vote on the OSLAP at the UNHRC in 2022, it got 7 votes, and the mechanism of the Accountability Project was actually strengthened and extended through the Resolution it lost.

Was the government worried that it may not gather even that number of votes (which was the lowest thus far) in favour of the country and thereby expose to Sri Lankan citizens, its lack of skills in building global support for its position at international forums?

Or was the Govt not serious about challenging the legitimacy of the Accountability Project and the “rejection” was simply throwing a bone to Sri Lankans anxious back home, an eyewash for public consumption, a show of bravado, which they never meant to follow through?

Slapping the OSLAP

Ambassador/Permanent Representative Himali Karunatilleka’s statement was clear. She said that Sri Lanka had fundamental objections to the Resolution due its reference to the Office of the Sri Lanka Accountability Project (OSLAP) set up within the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), the mandate of which had been extended in 2022 via subsequent Resolutions, and further extended this time in October 2025.

She explained to the Council that the issue was with “the external evidence gathering mechanism on Sri Lanka within the OHCHR, which, in our view is an unprecedented and ad hoc expansion of the Council´s mandate.” She further stated that Foreign Minister Vijitha Herath had “reiterated that Sri Lanka does not accept the external evidence gathering mechanism set up by the OHCHR…”

This mechanism set up in 2021 and strengthened and extended in 2022 according to the OHCHR website, and was established “to strengthen the capacity of the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) ‘to collect, consolidate, analyse and preserve information and evidence and to develop possible strategies for future accountability processes for gross violations of human rights or serious violations of international humanitarian law in Sri Lanka, to advocate for victims and survivors, and to support relevant judicial and other proceedings, including in Member States, with competent jurisdiction’”.

This alludes to Universal Jurisdiction, which means that unlike in the case of the International Criminal Court, one’s country (in this case, Sri Lanka) doesn’t have to have signed up to the Rome Statute to be prosecuted for such crimes in another country which decides to take up the case for prosecution in their own jurisdiction.

What could be done?

Since the current government objects to this prospect, what options were available in order to achieve a favourable outcome for Sri Lanka? It had an entire year to think about this and to exercise at least one option freely available to it, since this mechanism already existed for a few years.

Since Sri Lanka declared that the new mechanism was an “unprecedented and ad hoc expansion of the Council´s mandate”, setting out a generic criticism of the Office of the High Commissioner for exceeding the mandate, it would have been the logical thing to do to as a member of the United Nations, to convince as many members of the Council as possible of the dangers of such a precedence and the implications of it for all countries, and to convince them to oppose it for their collective benefit and of the UN system.

Since our diplomats are stationed in Geneva permanently, did the government instruct them to pursue this option? These efforts take time. Or did the government, including the Foreign Minister, simply pay lip service to these objections only at the very last session?

Did the Foreign Minister take this up with member countries of the Council when he visited Geneva in September? Did he take it up with his counterparts in other countries when he attended the High-Level Segment of the Human Rights Council in February/March 2025, with Ministers, Heads of State and other High Officials attending the sessions? Did Sri Lanka make a concerted effort to remove what they find so objectionable, from being further extended? Or were Foreign Minister Herath and the government unaware that this was a course of action available to them?

What does it say about the efficacy of their diplomacy as they opted to watch helplessly, unable to gather a minimum number of states to support them in their objections and rejection?

What really happened?

The truth may be more complex than it appears. China and Cuba, both influential at the Council and at the UN in general, also objected to this mechanism and disassociated themselves from the resolution on Sri Lanka. Why did the Sri Lankan government not use the leverage of these friendly states to garner support from other members of the Council?

Sri Lanka did not articulate any objections to or rejection of any other item in the Resolution. It had largely undertaken to do many of the things in the previous resolutions: Repeal the Prevention of Terrorism Act and appoint a committee to examine its repeal; amend the Online Safety Act, the reopening of investigations into some cases of human rights violations and the Easter Sunday bombings; to establish an independent public prosecutorial body, among other things.

In promising the Independent Public Prosecutor’s Office, they went much further than any other government to date, with the public yet unaware as to its contours, much like the (at least) 7 agreements signed with India by the Govt.

Therefore, the Govt had a good hand to play with, in any negotiations. Even after the Resolution was presented for consultations at these sessions (which is a mandated step in the process), was the Sri Lankan delegation unable to gather support for a debate at least on the one item (OSLAP) that they objected to? Obviously, the consultations with other states went cordially, as our Ambassador thanked them for their cooperation, positive suggestions and even amendments.

On behalf of Sri Lanka, our Ambassador questioned the “credibility, transparency of how this office was set up, its work and the budget.” She said after 4 years, there had been no benefit to the people of Sri Lanka. She said it only served “those with vested interests” and would “create division within the communities in Sri Lanka and will be counter-productive.” She said nationally owned processes were best suited to “address matters related to human rights”.

Having said all this and on that basis rejected the Resolution, why not have a member state which had already objected to this mechanism (China, Cuba), call for a vote on this “counter-productive” item on our behalf?

Inept at the international

The impression this course of action has left on the populace about this administration is one of incompetence and ineptness in dealing with the international community, inability to build a like-minded group of friends at UN forums, to gather their support to fight against one’s legitimate grievances in the international system. A TV station usually very supportive of this government, showed a member of their panel of journalists ask the government representative why they couldn’t secure a single vote for Sri Lanka.

This failure to negotiate their own preferred outcome for Sri Lanka, was predictable when this government decided not to attend the BRICS and SCO summits where they could have made or renewed contacts with the leaders of the emerging powers of the global South and lobbied their support in times of need. They are many, and wield great influence as a bloc and as individual member states at the United Nations.

It was also sadly predictable when Sri Lanka deviated from its traditional stance of standing up for others in their need, their visible, irrefutable and dire need such as in the case of Palestine, opting for vague and utterly bland language to call for peace at the UN General Assembly in reference to the raging war on Gaza, with many other leaders calling it a genocide. Sri Lanka showed itself to be playing safe and selfish, a bit player, in contrast to the time when it punched way above their weight, assuring support for itself in its own time of need.

(The writer is author of ‘Mission Impossible – Geneva’, Vijitha Yapa, Colombo 2017.)