Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Wednesday, 15 September 2021 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

From all accounts of expert economists, it appears that Sri Lanka needs a bailout with long-term, low interest loans, with a grace period to tide over the current economic situation that is going to prevail at least for another two to three years, if not more

Sri Lanka is at the precipice of an economic disaster. The country’s foreign debt is suffocating the country, it is its biggest immediate problem, and the problem for the foreseeable future unless urgent and drastic action is taken, now.

Sri Lanka is at the precipice of an economic disaster. The country’s foreign debt is suffocating the country, it is its biggest immediate problem, and the problem for the foreseeable future unless urgent and drastic action is taken, now.

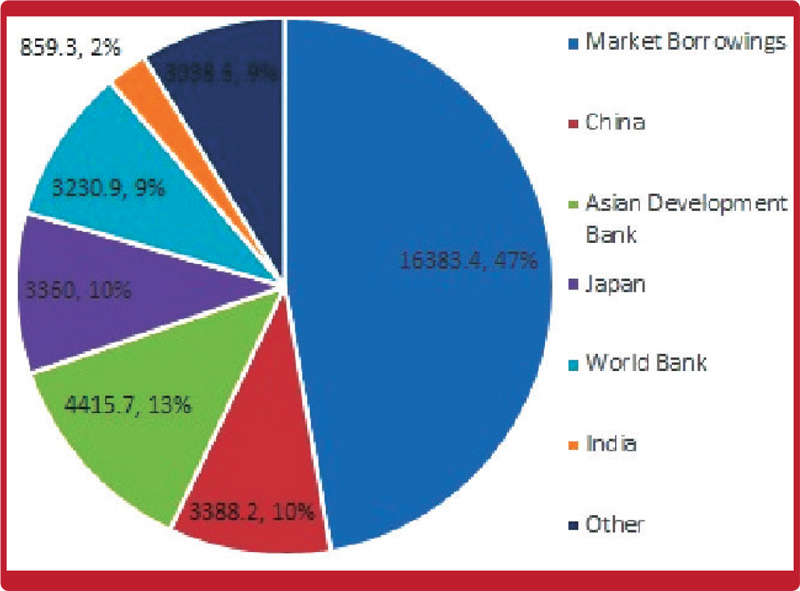

The crisis arises due to several factors, the primary factor being the high component of market borrowings in the form of International Sovereign Bonds (ISBs) in the country’s foreign debt portfolio. ISBs account for 47% of the debt, as shown by a Central Bank chart.

ISBs are short-term loans attracting high interest rates (around 6%) with no grace periods while loans from international institutions such as the World Bank, Asian Development Bank, IMF, attract low interests and long term repayment terms including grace periods. ISBs are usually not conditional while others like WB, ADB and IMF have conditions that a country has to fulfil to qualify for the loans. Besides the ISBs, the Chinese debt component is stated as 10% of the total debt. These loans are reportedly similar to short term ones as IDBs, and attract a higher interest like ISBs. If this is so, 57% of the loan portfolio is in high interest, short term loans.

In the absence of exports income that brings in a nett inflow to the country after accounting for the import component of exports, a serious drop in tourist earnings, foreign remittances and much anticipated FDIs not materialising, Sri Lanka will not have a choice but to take more loans in the form of ISBs and other high interest, short term loans, to repay loans and interest components that will be falling due.

Skating on thin ice

It is perhaps time that the country came to terms with the fact that we are skating on thin ice and pretending there is no berg at the bottom of the iceberg and only its tip. What is visible in an iceberg, its tip, is only a small part of the entirety of the iceberg, and Sri Lanka’s debt problem is that big part of the iceberg which politicians do not wish to see, preferring to see only the tip. The Titanic sank because of the underestimation of the unseen part of the iceberg it collided with. Sri Lanka could be the next Titanic.

In the past, Sri Lanka managed to settle large debt repayments with foreign exchange inflows from exports, tourism and foreign emittances, and also build a small reserve for a rainy day. Today that reserve is down to $ 2.5 billion, while our accumulated debt is around $ 35 billion without counting the interest component of this debt.

The spin that is given to Sri Lanka’s economic woes reminds one of very commonly used Australian and New Zealand expression, “She’ll be right, mate”. This is a frequently used idiom in Australian and New Zealand culture that expresses the belief that “whatever is wrong will right itself with time”. In recent years, the term has taken on a less than flattering connotation, with “a she’ll-be-right attitude” referring to a willingness to accept a low-quality or makeshift situation rather than seek a more desirable solution. This definitely rings a bell with regard to the situation in Sri Lanka. Postponing the inevitable, and administering stop gap measures seem to be the modus operandi that seems to be a common thread that links all politicians.

Economy in dire straits

Sri Lankan politicians of whatever hue, when they are in power, seems to be experts at deception with their feigned assessment of the country’s economic situation. It has never been more evident than now. Internal mismanagement over the years, the economic situation in the rest of the world on account of the pandemic, and not having a clear direction for now, and the next 10-20 years, have all contributed to this artificial situation.

The President and the rest of the country must come to terms with the fact that she, meaning the Sri Lankan economy is not all right. That is the first thing that must happen. The Sri Lankan economy, its structural fundamentals, and its financial situation is in a perilous state and that is a kind word to use to describe an extremely dire situation. The country has a short-term policy of virtually robbing Peter to pay Paul, and scraping money from any quarter in order to settle foreign debt, and fund essential imports in order to survive.

The direness of the economy is well explained by Umesh Moramudali, a lecturer at the University of Colombo, in an article titled ‘Sri Lanka’s foreign debt crisis could get critical in 2021’ published in The Diplomat (https://thediplomat.com/2021/02/sri-lankas-foreign-debt-crisis-could-get-critical-in-2021/)

The situation outlined by Moramudali did not start with the pandemic, nor just the current administration. Those currently in the Opposition should not clap and gloat that they would have done a better job. They have had enough opportunities to fix the problem, but they did not do so. This article is therefore not about who is to blame for what, but to throw open the question as to how one should reset the economic fundamentals and why.

The writer is no economist, but an ordinary pragmatist. It is hoped that readers will use their common sense and give thought to the issues mentioned here, use their common sense to question, debate and discuss, but importantly arrive at conclusions which are solution oriented and not ones that exacerbate the problems.

Steps to take

Firstly, the economic fundamentals and the foreign policy of the country, which have a relationship to global political relationships, have to be questioned, assessed, and reset where necessary. In a sense, one should question which side of the bread slice is buttered, meaning, if the country’s future is to be based primarily on export earnings, then questions like, where do we export now, where does the biggest future potential lie and whether our foreign policy is conducive to sustain and grow export markets needs to be questioned.

It is understood that Sri Lanka’s primary export markets are to Western nations and the country has a trade balance in Sri Lanka’s favour when it comes to these countries. On the other hand, China, a country very supportive of Sri Lanka at all times when others virtually abandoned it, reportedly has a substantial trade balance in their (China’s) favour. While efforts need to be made to address this situation, it should surely be important to examine whether Sri Lanka’s foreign policy is conducive or not to support the overall future direction of export markets and earnings.

The width and depth of Chinese economic associations with a multiple number of developing countries is substantial and is a reality that needs to be known and faced. Sri Lanka is well aware of this, and the extent of their portfolio of direct and indirect loan facilities, and equity participation is probably not known in its entirety by the public.

Sri Lanka however cannot go down the path it has been traversing for a considerable period of time, and it needs to diverse its own equity and loan facility portfolios with international bodies and countries who are their primary export markets. China too should become an investor in Sri Lanka and importer of products and services from Sri Lanka and not just a lender.

In relation to exports, it is not clear whether what is being reported as export earnings are presented as nett export earnings after accounting for the import component of the exported item/s. A gross export earning is like a mirage particularly where there is a very high import component. The long term future benefits will naturally accrue only if the import component decreases in order to give the exporter and the country a higher earning component. This is where a value adding export industry is needed and earnings increased either by using more and more local inputs, or where the exported value has a substantially higher margin over the imported component.

While Sri Lanka has been moving in this direction, this needs to be the policy that underpins the export industry. Tax incentives perhaps should be enhanced for export industries that have a substantial local cost component and/or where the value adding component is high. Much has been written about the need somehow to recommence tourism as soon as possible, and also to recommence overseas travel for workers employed overseas. Both income earners are critical for the country’s survival and it is hoped both will commence soon. However, both have an international dependency and therefore the status of the pandemic in other countries.

While it is an understandable reaction when faced with a devastating pandemic that has caused economic havoc throughout the world, to curtail imports and conserve foreign exchange, it is a very short term measure as many economists have pointed out.

Time for a bailout

From all accounts of expert economists, it appears that Sri Lanka needs a bailout with long-term, low interest loans, with a grace period to tide over the current economic situation that is going to prevail at least for another two to three years, if not more. The IMF is the only obvious institution that comes to mind to obtain such a bailout as that is more or less their core business.

Of course any such bailout will be conditional on Sri Lanka agreeing to major structural reforms. Some of these will be painful in the immediate to short term, but they will be less painful than the repercussions of an economic collapse or a marginal existence with ad hoc borrowings to sustain the country.

A weak economy will impact on the popularity and the credibility of a government and it will provide ample opportunities for Opposition parties to destabilise the Government. Political stability, the one key criteria that foreign investors will look for when they make decisions about investing in Sri Lanka, will be gravely impacted, and the much anticipated Foreign Direct Investments (FDIs) will be hard to come by.

All above economic worries will destabilise the rupee even further from its present status. Today, the market rate that commercial banks pay to purchase US Dollars outside of the Central Bank rate is said to be between Rs. 230 to Rs. 240 for one US Dollar although the Central Bank rate is Rs. 202. This dichotomy is real and it is not a fantasy according to reports from Sri Lanka. Many suspect that the real value of the Sri Lanka value is far worse and if allowed to float, it will sink Sri Lanka.

The current de facto devaluation is bound to exacerbate unless the country’s economy is stabilised, and its economic fundamentals are reset in such a manner that it can prepare the country for its next many generations and for them not to live a lie perpetrated on them by successive governments.

ISBs account for 47% of debt, according to this Central Bank chart