Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Friday, 2 August 2019 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Sathya Karunarathne

Sri Lanka has seen a rise in prices of rice since the latter part of 2013, with small and medium scale rice mills closing down and the Government having to import around two million metric tons of rice (2013-2018) to stabilise prices and maintain supply. The skyrocketing rice prices were traced back to large scale millers holding an oligopoly of trade, the said rice millers continuing to push down the purchase price of paddy from the price taking farmers and creating artificial shortages to drive up the prices.

Hikes in rice prices can also be traced back to 2016/2017 drought where 17 districts were affected. Millers were also strategically purchasing paddy soon after harvesting with a high presence of moisture, impacting the quality and price of the paddy purchased. The majority of farmers being small scale operators with financial burdens well beyond their capacity and limited bargaining power were left with no choice but to allow large scale millers to add premium claiming the need for electric dryers and longevity of storage. In short, large scale rice millers were purchasing paddy at low rates, milling the thus purchased paddy, warehousing it in large quantities, and releasing it to the market at much higher prices.

Upon identifying the need to address the existing controlling oligopolies in paddy markets, the Ministry of Economic Reforms and Public Distribution under the guidance of Minister Harsha de Silva took the initiative to introduce ‘Shakthi’ rice to the market on 30 March. The birth of Shakthi rice, however, cannot be narrowed down to a mere resisting mechanism against the controlling oligopolies. It is a result of a series of efforts taken by the Government to resuscitate the small and medium scale mill owners, thereby protecting the small scale farmer and the consumer burdened by exorbitant rice prices.

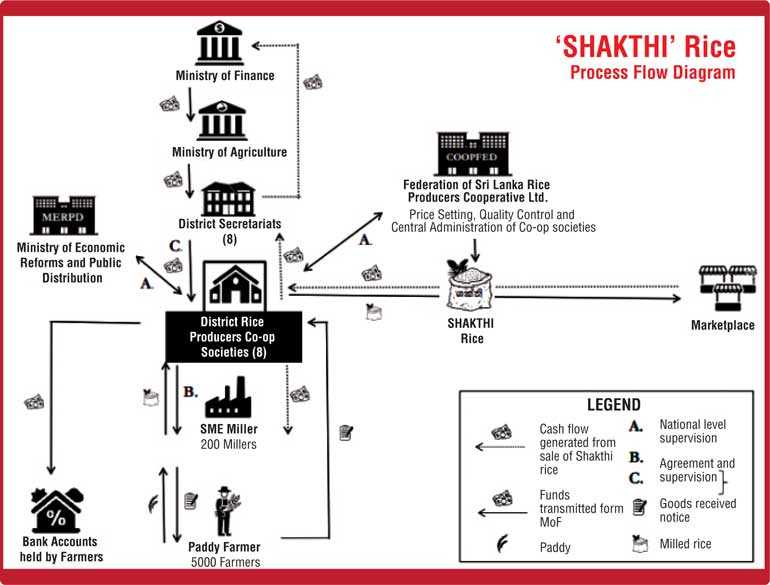

The Government announced on 13 February that it will disburse an interest-free working capital loan of Rs. 1 billion to small and medium scale mill owners to purchase paddy, mill it and resell to cooperative networks island-wide. This new scheme is implemented with the participation of the All Island Rice Producers Cooperative Societies where Small and Medium Scale (SME) rice millers have been organised into cooperatives spread out across eight key districts.

The Government will provide these cooperatives with funds and the said cooperatives will release money under an agreement to the millers who are their members. The millers will then utilise the funds to purchase paddy from the farmers, mill it and resell it to the cooperatives and finally, the cooperatives will sell it to the consumers. Shakti rice was introduced to the market under this cooperative network enabling the cooperatives to enter into the national rice supply chain.

In the fragmented rice supply chain the country was experiencing in the last few years the cooperative sector was on the rice distribution end. With this initiative the government has been successful in revolutionising the rice supply chain by allowing the cooperatives to step into the process of supplying, taking away from the control of the oligopolies.

The set guaranteed price by the Government to purchase paddy from the farmer is between Rs. 38 (White Nadu) to Rs. 41 (White Samba). However, if the miller was purchasing the paddy at this said guaranteed price the selling price should ideally be 2.1 times from the purchase price which is Rs. 80 to Rs. 85 in maximum price. Despite this Government regulation at play, the consumer had to bear the burden of rice being sold at the exorbitant price of Rs. 114 to Rs. 120 until May of 2019 due to the oligopolies that were determining the price.

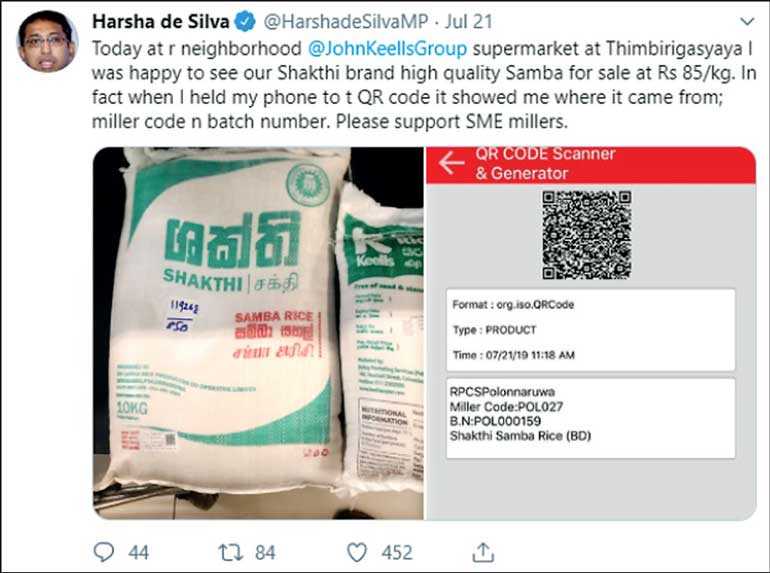

With the introduction of Shakthi rice to the market at a price ceiling of Rs. 80 per kg (White Nadu) and Rs. 85 per kg (White Samba) the leading rice millers were forced to reduce their prices to Rs. 90 to Rs. 95 per kg, further facilitating the reopening of closed mills belonging to SME rice millers and recreating competition that was lost in the oligopolistic structure.

Minister Harsha de Silva stated that the introduction of Shakthi rice or the loan of Rs. 1 billion rupees is not an interventionist attempt but an attempt to rejuvenate the small and medium mill owners so that it will help both the farmer and the consumer. He goes on to say that this is an attempt to put in place a set of policies where the Government can rectify market failure without creating a Government failure.

Thus introduced Shakthi rice under the new scheme is beneficial to the farmer in a plethora of ways the farmer has failed to experience before. The generally accepted line of thought is that big, medium or small scale, all rice millers exploit the price taking farmer. In looking at this phenomenon from a point of view of an oligopoly, except a handful of millers, the rest are in a strong competition. Given this strong competition, the SME millers would not exploit the price taking paddy farmer as they need to coexist and cooperate in battling the pressure exerted by the large scale millers.

Having observed this above mentioned exploitative cycle exiting in the paddy value chain the government identified the need to level the playing field between the SME rice millers and the large scale rice millers. It is in identifying this need that the Government intervened in strengthening the SME millers. While ensuring the rejuvenation of the SME millers the Government also had to ensure that the farmer is not exploited by the thus strengthened SME rice millers or even further exploited by the large scale rice millers.

Under the introduced new scheme, the Government has given for the first time an opportunity for the SME millers to rally under a cooperative system ensuring that the previously price taking farmer is now presented with their lost bargaining power. In the previous oligopolistic market, the farmer had no bargaining power as the majority of farmers are small scale operators. They did not have the privilege to enjoy economies of scale due to their scale of operation and the level of employment of productive factors.

The price taking farmer was left with little to no chance of making a profit due to the extremely high cost of production. Simultaneously at the point of production, the farmer was at unbearable amounts of debt due to financial commitments made on credit basis on harvesting machinery, fertiliser, seeds and other necessities from informal credit agents, most commonly. This leaves the farmer with little room to delay the selling process, leaving the farmer with no choice but to succumb to low prices of purchase offered by large scale millers, often having to sell paddy without drying.

With the revival of the SME millers, the farmer is now presented with the opportunity to bargain as the SME millers are strengthened under a large cooperative group and being able to offer the farmer a price that can compete against the prices of purchase presented by large scale millers. This further improves healthy competition that was almost non-existent in the previous oligopoly. ‘Shakthi’ as a monitored brand ensures a guaranteed price of Rs. 38 to Rs. 41 per kg further leaving less room for the farmer to be exploited.

The introduced cooperative system is embraced by the strained SME millers as it presents the millers with a system of operation that protects them which has never been in place before. This concept of a co-operative system was built on the cabinet decision taken on 31 July 2018, to provide credit facilities to SME millers through the MCF (Miller’s Cooperative Federation) and not to take legal action against SME millers who have failed to settle previous loans.

Building on this and developing the cooperative sector towards rice-producing, the government has been able to revolutionise the paddy value chain while protecting the SME millers. For the first time, small millers are given the opportunity to rally under a district-based cooperative society for crucial loans, giving them the opportunity to not sort to unofficial credit lenders. In other words, the co-operative society system in place is a mechanism to source loans for the millers registered under the said cooperative societies, who otherwise struggle for loans due to the informal nature of the cooperative sector.

The eight district societies are autonomous in their function but are subordinate in hierarchy to the District Secretariat through which the millers receive and repay their loan requirements.

The platform thus provided for the SME miller to rally under eight district co-operative societies bound by a collective identity and an end goal results in the said SME miller being presented with stronger bargaining power. These eight cooperatives are monitored by the Assistant District Co-operative Commissioner or the Assistant Divisional Co-operative Commissioner as relevant. These two bodies also assess the working capital loan requests made by the SME millers through co-operative societies.

Financial assistance to mill owners is provided under the supervision of the District Co-operative society to whom the approved loans are passed down from the Treasury who allocates the loan of Rs.1 billion via the Ministry of Agriculture to District Secretaries who in turn liaise with the Assistant District Co-operative Commissioners. This co-operative mechanism offers SME millers with a competitive price and the ability to work with a common brand name.

In most instances, small scale millers would offer additional payments in buying paddy in order to attract local supply and the middle scale miller feels the pressure to compete with large scale millers in order to secure paddy supply to them in a given area often when the large scale miller operates with a large collection network. However, the middle scale miller cannot compete with large scale millers in selling rice due to their lack of machinery and other necessary factors needed for high-quality production resulting in SME millers not experiencing economies of scale.

The Government in introducing the cooperative mechanism has introduced a system through which the SME miller can be strengthened financially providing them with the necessary collateral to attract formal loans.

The SME rice miller can be identified as the consumer safeguard mechanism in play as the small miller presents price hikes and protects the consumer by stabilising prices and by lowering the prices from the exorbitant rates that existed in the oligopolistic system. The consumer is also benefited by the improvement in the quality of production by the SME millers as they are strengthened to compete with the quality of the large scale millers.

[The writer is an Analyst at the Economic Reforms Analytics Unit (ERAU) of the Ministry of Economic Reforms and Public Distribution. She has a BSc in International Relations (University of London) and a BA in English Literature (University of Sri Jayewardenepura).]