Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Wednesday, 11 September 2019 00:30 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Sri Lanka’s public debt has continued to rise. This has put enormous pressure on the Government budget as well. Interest payments on public debt consumes a large part of Government revenue and represents a large portion of Government expenditure. In turn, budget deficits will continue to be financed through more borrowings, thereby increasing the amount of public debt.

In an environment of subdued economic growth, managing the budget deficit becomes even more challenging due to the decline in revenue and need for fiscal stimulus to support the economy. Economic growth, fiscal deficit, and debt combined pose the biggest challenge to the overall macroeconomic stability of the country. Obviously, the country has to walk a very tight path in the coming years.

Public debt has continued to increase at a higher rate

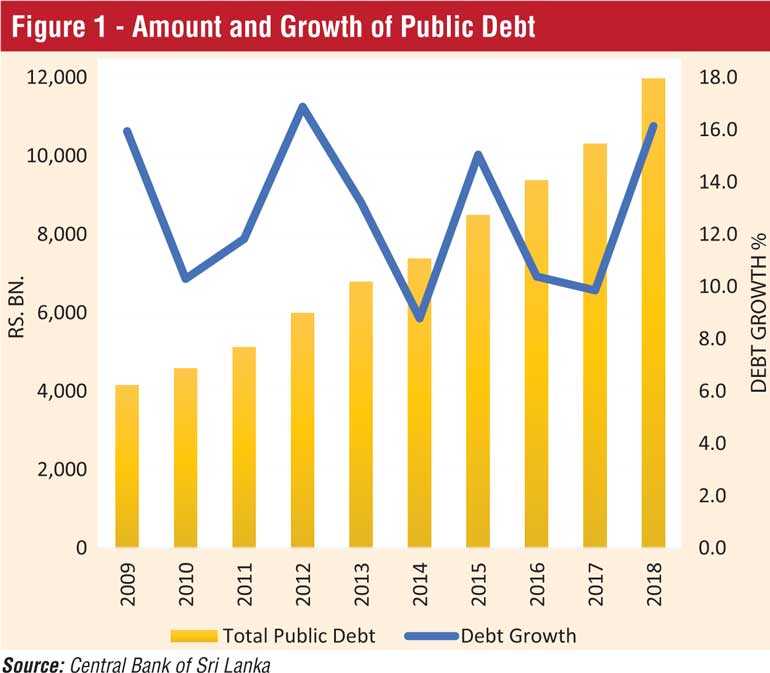

It is important to get a perspective on the amount and growth of public debt over time. Sri Lanka’s public debt amounted to Rs. 12 trillion at the end of 2018 (Figure 1). In fact, according to the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, the total debt was Rs. 12.6 trillion as of June 2019.

In terms of growth, debt has more than tripled over the 10-year period from about Rs. 3.6 trillion in 2008. During the same time period, debt has grown at a rate of about 13% a year. At this rate of growth, debt will double to Rs. 24 trillion in about six years. Clearly, such an explosion of debt at the current economic growth rate of about 3-4% is not sustainable.

Public debt is 83% of the economy

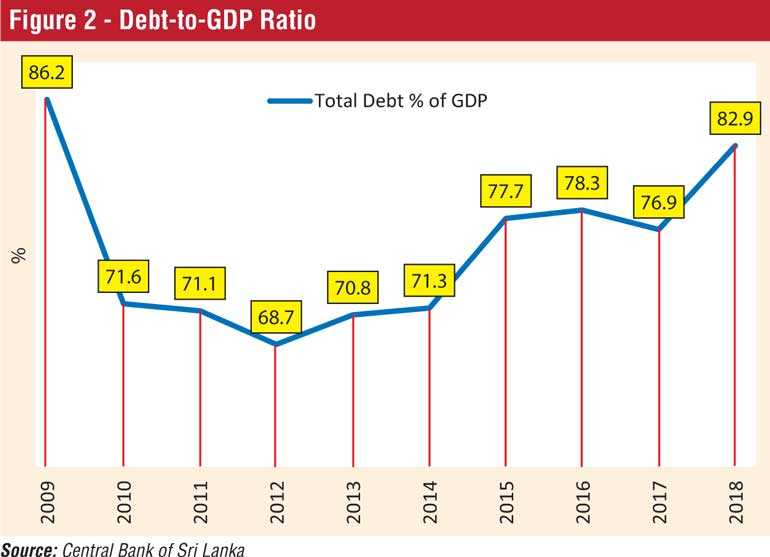

A widely used indicator of public debt level is debt as a percent of the economy, which is measured by the GDP. In relation to the 2018 nominal GDP of Rs. 14.5 trillion, debt stands at 83% of GDP. The debt-to-GDP ratio was 86% in 2009, the final year of the civil war.

Although the debt-to-GDP ratio declined in the subsequent years, reaching 69% in 2012, it has continued to increase since then, with the exception of a small dip in 2017 (Figure 2). Two of the largest increases in the debt-to-GDP ratio occurred in 2015 and 2018 when it jumped up by six percentage points in each of the two years.

This amount of public debt and its rate of recent increase sound an alarming bell. To give an international perspective, when the eurozone was created, the member countries agreed under the Maastricht Treaty to both a 3% deficit-to-GDP and a 60% Government debt-to-GDP limit in order to provide fiscal discipline to the common currency area. Although there is no agreement on the optimal level of debt, a debt level of 60% of the GDP can reasonably be sustained.

While Sri Lanka might justify a ratio higher than the 60% level given the large financing needs necessary for economic development, its current rate of economic growth and fiscal capacity to pay cannot justify the current level and growth of public debt.

Foreign debt is now half of the total public debt

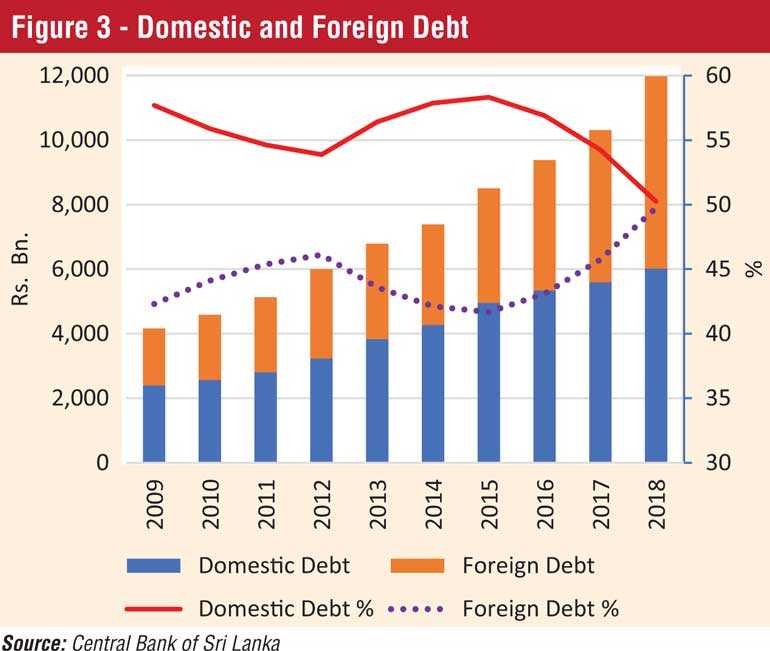

An important aspect of debt is its composition between domestic and foreign debt. As of the end of 2018, Rs. 6 trillion of Rs. 12 trillion – 50% of total debt – was foreign debt (Figure 3). As of June 2019, Rs. 6.3 trillion of Rs. 12.6 trillion debt is foreign debt. As a result, foreign vs domestic debt is now 50/50. How did we get to this point? Foreign debt was 42% of the total debt in 2009 and rose to 46% of debt by 2012. Although foreign debt declined to 42% by 2014, since then it has increased continually, resulting in a share of 50% of debt now.

On the flip side, while foreign debt has increased from 42% to 50% between 2014 and now, the share of domestic debt has decreased from 58% to 50%. This 8% shift from domestic to foreign debt over a four-year period is quite alarming and clearly shows the increasingly more reliance on foreign debt as a source of financing by the Government.

Thus, not only has the total public debt reached high levels, but also more and more debt is now foreign-denominated debt, which requires Sri Lanka to either earn foreign currency or borrow more from abroad to finance the payment of interest and principal obligations on such debt.

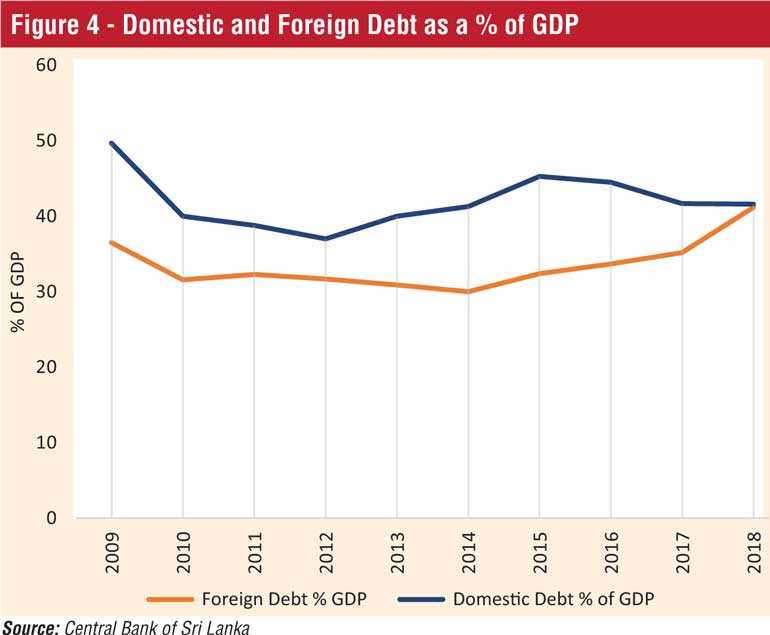

Foreign debt represents 41% of the economy

It is also useful to examine domestic and foreign debt in relation to the size of the economy. As a percent of GDP, foreign debt declined from 37% of the GDP in 2009 to 30% in 2014. Since then, foreign debt-to-GDP ratio has increased by 11% percentage points to 41% as of the end of 2018. In the meantime, the domestic debt-to-GDP ratio has declined from 50% of the GDP in 2009 to 42% in 2018.

Debt growth in 2018 is startling. In 2018, total debt as well as foreign debt recorded one of the largest increases in recent years. Total debt grew by 16%, representing the second highest increase in the past 10 years. Foreign debt rose by 26%, making it the largest increase in the past 10 years. At these rates of growth, foreign debt could easily overtake domestic debt as the largest financing source in the Sri Lankan economy, making Sri Lanka highly vulnerable to external shocks.

Economic implications of high debt are potentially pernicious

Economic implications of high levels of debt are well known, particularly after the Greek and eurozone debt crisis.

Burden on Government budget

First and foremost, interest payments on debt have created an enormous burden on the government budget. Interest cost alone was Rs. 852 billion in 2018. This amounted to 42% of Government revenue and 6% of the GDP in 2018. With rising debt, the interest burden will only continue to grow. The 2019 government budget envisages a total interest burden of Rs. 913 billion for 2019 and Rs. 1,000 billion for 2020. So, the trillion-rupee interest burden is not too far away.

Limited fiscal space and flexibility for development

Higher interest costs reduce the fiscal space and flexibility. As seen from the above numbers, higher interest costs severely limit the availability of financial resources for the government to spend on other recurrent expenses and public investment.

In 2018, the interest cost represented 31% of the total expenditure. The negative impact on the development expenditure is very visible. Since 2016, interest costs exceed the amount of funds spent on public investment.

Lower resources for fiscal stimulus

Furthermore, revenue drain through interest costs severely limits the government’s ability to respond to economic slowdowns, such as the one we are in now, in terms of fiscal stimulus either through tax cuts or increased government expenditure. That can lead to prolonged downturns which will in turn exacerbate budget deficit and debt problems.

Deterioration of credit quality

Economic and financial consequences of debt build-up could ultimately lead to a deterioration of the country’s credit quality and the sovereign credit rating. Sri Lanka’s credit quality is already weak. All three major credit rating agencies downgraded Sri Lanka’s sovereign rating to the ‘B’ (S&P B, Fitch B, Moody’s B2) due to refinancing risks and uncertain policy outlook.

This rating indicates highly speculative debt where capacity for continued payment is vulnerable to deterioration in the business and economic environment. Further, the build-up of debt without improvement in budget deficit, economic growth, foreign currency reserves etc. could further weaken the sovereign credit quality.

Debt refinancing risks

Any further weakening of Sri Lanka’s credit quality could elevate refinancing risks of foreign debt. To pay interest and principal obligations of the existing stock of foreign debt, Sri Lanka will need $ 5-6 billion in each of the next five years. Any deterioration of credit risk could raise the country risk premium, thereby increasing the interest cost of future borrowings needed to rollover existing debt.

Currently, Sri Lanka’s 10-year sovereign bonds yield is about 7.4% whereas the 10-year US Treasury yield is 1.6%, resulting in a country risk premium of about 5.8%. However, several factors other than higher levels of debt could cause the country risk premium to increase.

Slower growth and heightened political uncertainties due to the upcoming elections cycle could cause international investors to demand a higher risk premium for investing in Sri Lankan Government bonds. What might work to the benefit of Sri Lanka is the current lower interest rate outlook worldwide. It is possible that higher country risk is somewhat offset by the lower interest rates in international capital markets.

Debt distress and restructuring

Ultimately, the country could fall into debt distress, if public debt continues to grow unguarded at the current rate of growth without material improvement in economic growth and fiscal deficit. Debt distress is where the country faces difficulties in meeting debt service payments. Such a situation might require debt restructuring.

In conditions of debt distress and restructuring, countries implement economic austerity programs in which government budgets tighten, economic activity shrinks, creating difficult economic conditions for the people. Obviously, it is in nobody’s interest to let the country slide into such as state of affairs.

Need to recognise the problem and implement a growth-focused economic plan

The high level of public debt is not sustainable in the long-run. Given the continued fiscal deficit, the Government will be forced to continue to rollover existing debt as they mature and, as a result, reduction of existing debt will be a significant challenge. The Government projects that debt will decline to 70% of the GDP by 2023. It is indeed good if that happens.

In the final analysis, reducing debt will require a strong policy framework for fiscal consolidation and achieving sustained economic growth in high single digits for at least a decade. And that is possible. Sri Lanka can accomplish it with a strong economic vision and a long-term socio-economic development plan supported by professional economic management and political commitment.

(Lalith Samarakoon is a Professor of Finance and Financial Economist. He is also a Chartered Accountant and a Certified Financial Analyst. Currently, he serves as the Secretary-General and Chief Economist of the National Economic Council of Sri Lanka. Follow Perspective at www.lalithsamarakoon.com and Twitter @LSamarakoon. Email feedback and comments at [email protected].)