Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Saturday, 13 December 2025 00:27 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Surya Vishwa

By Surya Vishwa

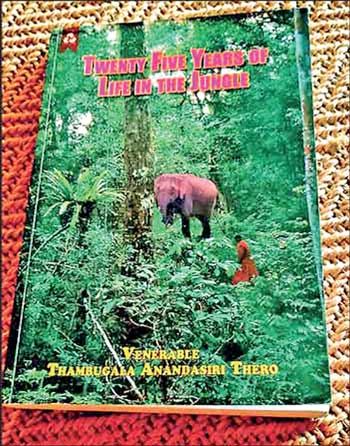

Authored by Venerable Thambugala Anandasiri Thero in the Sinhala language, the English translation of the book ‘Twenty Five Years of Life in the jungle’ is by Kamala Rajapakse, printed and published by Dayawanse Jayakody and Company – Printers. The overall location we are in is the Kudumbigala forest hermitage (Aranya Senasana) located in the jungles around eight miles west to the Eastern coast of Sri Lanka where Panama is the closest town.

We re-commence from chapter 9 titled Grandpa Samithambi which is about a centenarian, and despite his name indicating otherwise, a Sinhalese, an exorcist and a physician, well known and feared in Panama and elsewhere for his skills which included the ability to use cosmic energy to end mortal lives. The story in this chapter resonates with the human spirit of evolving to its highest potential despite the murkiest of pasts and Grandpa Samithambi who had become a Buddhist monk had a past that could be compared with Angulimala who became a revered monk under the influence of the Buddha. This chapter deals with the astonishment of those who knew Grandpa Samithambi when they heard that he had become a Buddhist Monk and how they regale Ven. Thambugala Anandasiri Thero about his past deeds or rather misdeeds. One man in the outskirts of the jungle had quipped thus to the Venerable Thero: “Oh, Reverend Sir. For Quietening such a man as this, you would definitely attain a state no lesser than Buddhahood.” When the Thero inquired whether he was such a cruel man, the reply had been that the murders done by him amount to the hairs on one’s hand! How did he kill? Was it with clubs or guns? No. It was with the mystic and cosmic linked arts Grandpa Samithambi had learnt from his forefathers. The revelation of the Buddha that everything begins and end with the mind is explained best by the feared Grandpa Samithambi when the Venerable Thero had inquired how he had exactly ‘mystically’ killed people. Grandpa Samithambi, had thus replied. “I have not murdered anyone. But when they know of the talismans and incantations in my possessions they fear me.” He had then listed out some of the ways in which he used to connect energetically with the universe and had noted that the mystic arts he knew were a mere one third of the secret knowledge of his forefathers, reiterating that the negative impact occurs only through the fragility of the mind. For a discerning and introspective reader, it would merit a deep contemplation on the link between the human mind and the living energy of the cosmos. This would also help us understand that everything upon this earth has life and thereby a consciousness. That every intention has a consequence. And that it is this action that is called Karma which we can describe as infinite universal imprints where every word, thought and action in interwoven across time and space and recorded in etheric loops, netting and connecting all of life. Grandpa Samithambi who was the senior most Kapurala of the Ampitiya Devale in Panama gradually transited from that role as he entered into the compassionate path of the Buddha. In one of the conversation with him in this transitional phase, the Venerable Thambugala Anandasiri Thero had explained as follows: “Now Grandpa. Learn well this lesson. You are a virtuous man who has found refuge in the Buddha, Dhamma and the Sanga. You are one who is respected by God/s,” The Ven. Thero notes that when he said this that the happiness of Grandpa Samithambi knew no bounds. This chapter merits a deeper reflection on who or what we think are God/s or God or Devas, deserving a deep introspection into the religio lingua of different ‘religions,’ the experiences and histories of the founders of these paths. Now labelled and fought over as ‘religions.’ A thorough comprehension of the cultures/nature/geography/traditions and how they are shaped by the environment (in Sinhala we can say Sobha Dahama – translated as the nature that is spiritual/wise) will require calisthenics of the mind to think and re-think but the time we spend in this pursuit will help us understand that all ‘religions’ begin and end with mother earth and all of the universe, the religious ‘rules’ or faith traditions influenced by the immediate geography of the earth location (eg: If it is a desert with sand storms/arid land/luxurious verdant soil with forests/many creatures of the wild/rivers/seas. When we go through the rest of this book, it will help us to lay a foundation to the link between human consciousness and phenomena linked with earth and its non-human beings.

In chapter 10 the title states The Veddah of Karambagala and we continue to hear the stories the one fearsome Grandpa Samithambi shares with the Ven. Thambugala Anandasiri Thero. The chapter begins with what could only be described as Grandpa Samitambi’s infinite cosmic appetite where he tells the Thero that he consumes (at one meal) 150 maize cobs and a minimum of two ripe jackfruits provided the seeds are baked and eaten at the same time! This would make the reader understand that Grandpa Samithambi needed to eat much of the earth energy through its vegetation offspring to muster the mental stamina for his trysts with the unseen! Incidentally he had also boasted to the Ven. Thero that he could clear areas of jungle land that needs at least six people all by himself, confiding that each tree type or shrub or creeper has a particular times where they can be easily disconnected from their roots.

“Those who do not know this simply tire themselves,” Grandpa Samithambi had noted. The conversation then had meandered to the Veddah of Karambagala who used to walay caravans that used to pass through the jungles (this was during the colonial time period). The Veddah was not consummately interested in the riches within the caravans carted by the Sinhalese but he needed the flesh of the bulls who drove those caravans. He also had a fondness for betel and arecanuts which he would pile up in his forest cave. The Veddhah of Karambagala is described as a ‘young ruffian’ which created such a menace that there was a call for his head by the colonial village administrators. He did not harm any of the people but the buffet of caravan bulls were an attractive option and an alternative to hunting.

Apprehending him being impossible, the Rate Mahattaya, the village chief, finally managed to coerce a thug, a wrestler from the village of Halawa who was known to possess the strength of seven or eight men. Lured with a nice meal of rice and betel at the mansion of the Rate Mahattaya, the thug reluctantly accepted the task of capturing the young Veddhah caravan bull eater. He respected the Veddah and there had been much persuasion by the Rate Mahattaya for him to undertake this dubious mission. The village wrestler had finally accepted, requesting manpower assistance of about eight strong men, a rope, betel with arecanuts, tobacco leaves, bark of Nellu leaves and other condiments for a grand chew.

Finally the day arrived for the grand trap that would end the tumultuous life of the Veddha whose name had been Hoora. The village wrestler had genially accosted him in the forest at his rock cave, announcing that he specifically came to meet him to offer him betel and acreanuts. The Veddhah was probably used to being venerated by earth mortals such as himself who possess much strength and live off the grid of society. Therefore beaming that a villager—a fellow youth came to meet him and offer him his favourite goodies he had unsuspiciously indulged in almost everything that was offered—the end effect being intoxication. The wrestler meanwhile was preparing for the grand attack and had picked up the bundle of bows and arrows of the Veddhah, as if examining it and then placing it near the edge of a cliff where he could kick it down when needed. Soon as the betel happy Veddah bent to spit out his chewing, the village thug had delivered a strong blow and then many other whacks. The Veddah although not sober rose to the occasion but finally succumbed to a immobile weak state at which point the eight men selected by the Rate Mahattaya tied him up with the rope they had bought with them. The bundled up Veddah was taken to the Rate Mahattaya as villagers gaped to see the elusive, caravan disrupting Veddah shackled and helpless. The wrestler meanwhile had curtly informed the Rate Mahattaya not to request of him such mean tasks in future and taken his leave abruptly without waiting for any reward or refreshment. The Rate Mahattaya facing the Veddha had appealed him to stay away from Karambagala and caravans that passed through it, promising to demark some areas in the forest where he can hunt freely. He had tried to convince the Veddah for days but the young man of the wild, declaring that life was useless when he was humiliated by being beaten refused all what was offered, bit his fingers in sad and desperate fury and died, not eating a morsel or a drop of water offered by his captor.

Chapter 10 is titled Through Yala to Kutumbigala traces a journey on the road to Situlpawwa, en route, by foot, from a religious mission in Ruhuna and entering the jungle from the Yoda Kandiya. Venerable Thambugala Anandasiri Thero had seven other monks travelling with him and four villagers. As night fell a rock slab was selected to sleep on and the Bandhu Piritha was chanted, considered a powerful protector and used by forest based monks. However in the dense, dark mystery of the jungle punctuated by eerie forest sounds, animal howls and rustling sleep comes scarce. A night prowling bear who had come to investigate the rare presence of so many humans in his territory had placed his muzzle against one of the pilgrims. That had been the end of attempting to sleep in a jungle outside the known caves which although in the thick of the forest were by now recognised by the forest beings as sacred places where monks lived and meditated. The rest of the night was spent in Pirith chanting and Dhamma discussions. In the morning devotees of Yoda Kandiya had arrived in a vehicle and the return to Kitumbigala had continued.

NOTE: The book Twenty Five Years of Life in the Jungle is being serialised as part of the education series commemorating national reading months (September to December) in Sri Lanka. This is an initiative in collaboration with the Residential Library of Healing in Hawa Eliya in Nuwara Eliya. Functioning with a mission to bring humanity back to nature this library, located at the summit of a mountain remains currently under the red zone of the Government. We do not know what the fate of this place would be. Repeated calls to the Commissioner of Nuwara Eliya and the Personal Secretary to the Mayor, to help rescue the books within which has served the nation in many ways including mass communication curricula writing for a national university of Sri Lanka, has remained un-answered. The below link written by a foreign tourist who was a resident of the library has been sent to both the Nuwara Eliya Commissioner and Secretary of the Mayor. It has so far remained unacknowledged. We are looking for a nature surrounded place anywhere in Sri Lanka, to relocate. Please call 0713693698.

https://www.ft.lk/travel-tourism/Sanctuary-in-Clouds-What-residential-library-of-healing-in-Nuwara-Eliya-meant-to-me/27-785479