Wednesday Jan 07, 2026

Wednesday Jan 07, 2026

Saturday, 18 October 2025 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Trees. What are they? Are they mere inanimate produce of soil that man can control – birthing and killing according to monetary benefit – by planting and decapitating them at appropriate time – when they have grown to an extent sufficient to fund man his need, want or greed? If we are answering this question from the point of commercial forests, the answer is yes. These are forests that man creates for lucrative benefits where nurturing the trees are only for the sake of what they would eventually provide him – their lives.

While it can be argued that commercial forestry has its need, we in this piece of writing are going to focus on life of trees as they are lived in, within the sphere of their own autonomy and freedom. They are born as decided by them, mature, grow into love and regeneration at their own pace and bring up their ‘children,’ beautiful green babies, according to their own protocol. Man, his assumed superiority, (his delusions about knowing everything), his infant modern science and his preoccupation with merchandising everything in this planet do not contaminate the happiness of these trees.

|

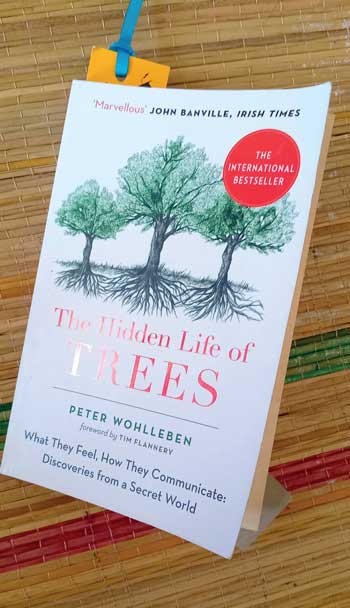

| Books as healers – Pic courtesy Frances Bulathsinghala of the Library of Healing in Sri Lanka |

By the Harmony Page Team

The information provided in this article is based on the book – ‘The Hidden Life of Trees’ and is being produced in four segments to honour the months from October to December as the national months dedicated to reading. (Alongside, for the next few weeks we will feature knowledge from several books falling into the categories of nature, sustainability and comparative spirituality. This series is curated and facilitated by Sri Lankan writer and developer of integrated knowledge training, Frances Bulathsinghala. The books are provided through her Library of Healing where books are promoted as therapeutic agents of solace and comfort – and stimulus for genuine ‘thinking’ and ‘creating’ – from art to entrepreneurship – (not streams of texts to be jammed into the brain for the purpose of passing exams.

Note: This series is hoped also to serve as possible workshop material for national libraries in Sri Lanka. It was originally intended for a workshop that was to be carried out by an initiative the Harmony page was associated with, at the Nuwara Eliya Public Library on 19 September on invitation of the Nuwara Eliya Municipal Council and the Public Library of this district. Unfortunately, reflecting the collective national disinterest in befriending books and the wealth that they carry, the scheduled workshop had to be cancelled owing to lack of ‘readers’ of the library attending it.

The mental makeup of trees in natural forests

Let us now ‘read’ into the lives, behaviour, quirks, happiness, unhappiness, lifestyle, and family life of trees.

The Hidden Life of Trees is authored by forester, Peter Wohlleben, originally launched in German as Das geheime Leben der Baume. The Hidden Lives of Trees was first published in the English language in hardback by Greystone Books Ltd. in 2016 in Vancour, Canada. The paperback edition was published in the United Kingdom in 2017 by William Collins as an imprint of Harper Collins Publishers of London.

As per the applicable copyright regulations we are not directly quoting from the book. We will be explaining, interpreting and elaborating its essence, as relatable to the Sri Lankan context – and serving as an extended Harmony Page media intervention that is linked to promoting the understanding the psyche of rainforests.

https://www.ft.lk/harmony_page/Exploration-into-Natural-Intelligence-of-a-rainforest/10523-782595

https://www.ft.lk/harmony_page/Relevance-of-forests-for-biodiversity-education/10523-782843

The earth is a tabernacle of sacredness – an enchanted mystery. Carved into human consciousness across time through varied images of the fantastical – many human childhoods have been shaped by man’s imagination chiselled through the many winding arms of the children of the forest – trees. This is pointed out in the foreword by Tim Flannery who explains the slow and longevity based time scale of trees. He uses as an example one of the oldest trees on earth, a spruce in Sweden which is more than 9,500 years old – around 115 times longer than the average human lifetime. This attention into the time factor difference that governs the lives of trees when contrasted and compared to homo sapiens sets a foundation that helps us understand the depths of the rationale of why trees ‘behave’ in such a different way as us.

‘Behaviour’ of trees

This ‘behaviour’ of trees was over time observed by Peter Wohlleben when he was managing the Eifel mountains in Germany. In the introduction of The Hidden Lives of Trees he reveals that why he wrote the book was because he wanted to list out what the trees that he lived amidst as part of his work, taught him. Here he points out that when he wrote the German version of the book the readership response showed him the relatability of what he wrote based on one patch of earth – on the high mountains in Germany – with all other locations of natural woodlands. What he cites here resonates in the human world in a manner where we can say that all those who wear human skins – whether they be yellow, black, white or brown has one main humane construct that is the same whatever sphere of the earth they occupy.

Likewise, the author brings note to the fact that we are not the only ones engrossed in our own unique dramas. There are apparently more interesting and epic ones being played out in the tree and forest world. His familiarity with the struggles and strategies of beeches and oaks as they chart out their existence amongst the ‘natural’ masses of other tree beings is made in sharp paradox to forests planted by man for commercial gain. It is possibly like comparing free man going about his joy in what he wants to do freely, at his own comfortable pace and for the purpose of the holistic, as opposed to man held in chains and ordered to produce tasks as demanded and under specific regulations that determine how he lives and how he dies.

In tracing the psychology of natural forests, the author shows the power of the collective – of trees – when they exist together rather than as a singular presence and how undisturbed and completely naturally evolving masses of plant-life; forests, is the determining factor of the future of humans and planet. In the first chapter titled Friendships it is shown how trees are greatly philanthropic and selfless, supporting each other with nutrition from bases of roots when necessary. One stark example given is how the gnarled tree stump felled about five hundred years was kept ‘alive’ with a greenish layer – found only in chlorophyll which is stored in living trees. The conclusion that Peter arrived at is that the ‘sugar’ that living tree cells must have as food – as consumed by those around, were being shared with the ancient tree stump. This forces us to think out two other comparisons between trees and humans.

Nature based sugar is a lifeforce for humans and so it is for trees. The contrast however in assessing how the ancient tree stump was kept alive by other trees by sharing their own nutrients, is that unlike man who is obsessed by individual survival at the cost of others’ lives (as in our wars), that trees display the opposite. Trees then could be decreed as being distinctly wiser than man in recognising the importance of life and sharing lifeforce.

The author also writes how scientists in the Harz mountains in Germany vouched for this interdependence – where ‘food’ was exchanged in times of need. Kind and selfless humans behave in the same manner as we see around us – possibly to a lesser extent that trees!

However, it is emphasised that trees in planted forests do not have his empathy.

They adopt the persona of loners and are incapable of relating to each other – because their roots are damaged when planting. Thereby Peter Wohlleben notes that planted forests – most of the coniferous forests in Central Europe ‘behave more like street kids.’ This is indeed how street kids would behave – when their familial ‘roots’ are damaged due to them being ‘disconnected’ or ‘uprooted’ from what is natural and forced to be ‘planted’ elsewhere.

The language of trees

Chapter 2 of this book covers The Language of Trees.

Once again it is astonishing to know how similar we are to trees in the world of communication. No, they do not have voices – but do humans only communicate through sound? Why then would we spend enormous amounts of money on perfumes? As the book The Hidden Lives of Trees point out, trees communicate through scent just as humans do by olfactory stimulus. In another parallel to humans as we functioned with our authentic senses from ancient times it is shown by quoting scientists on how humans chose who they would like to procreate with through the instinct of the natural odour of their body. The trees as a mass are like humans ‘scent’ centric beings.

In one incredible example it shows how in the African Savanah the umbrella thorn acacias the giraffes were feeding on got so irritated with this feasting liberty that they produced toxic substance into their leaves and also ‘communicated’ to neighbouring trees not to allow an adjoining giraffe buffet by emitting a warning ‘gas.’ Similar examples are given in how many plants get miffed when some creature choose to nibble upon its tresses. It is also stated that when a caterpillar munches on a leaf that it sends out an irate electrical signal just as a human would (if say for example an insect chose our cheek as a snack spot).

The defence mechanism of trees is apparently the ability to produce different compounds that serve the need of the hour. For example, they can call out to predators that eat up insects – if these insects become a nuisance to the trees. The trees then like humans share the ability to identify who our friends and foes are! It is stated in the book that the entire animal world is wired into the communication network of the trees so that they recognise and respond to the alarm calls of trees. Those who feed on critters who attack trees enthusiastically flock to the rescue of a desperate tree, happy also to fulfil their own gluttony.

Crisscross of information systems

To describe the ‘mass communication’ of the collective, the interesting term ‘wood wide web’ is used by Peter Wohlleben. This collective includes trees, shrubs, grasses and fungi – creating a crisscross of information systems operating above and below earth. Fungi meanwhile are said to nurture their own ambitions but ‘amenable’ to conciliation. Being cut off from the fungal filigree could isolate a tree keeping it away from the latest news, the book reveals. (Just as we would, say if we flee to the moon because the arid, forestless earth is no longer inhabitable (we would miss the news that there is no earth to return to).

Meanwhile, it is explained that if trees are weakened their conversational skills deteriorate and that insects and pest seek out these health compromised trees. Just as viruses (both natural and lab created) would seek out humans with weak immunity.

Chapter 3 of the book is titled Social Security where it is shown that tree species of natural forests bond through caring and sharing – where trees synchronise their photosynthesis performance so that they are ‘equal’ in their wellness. In contrast to the survival of the fittest mode attributed to humans, the existential edicts of trees seem to be the opposite. Apparently there are many volunteer ‘tree nurses’ in the forest who cannot bear to see anyone struggling with illness. It is the sense of ‘community’ that apparently keeps their happiness intact. Trees have realised what humans have not. That divided – when one singular tree become feeble and die – that this loss is significant in the plural – that each singular loss impact the entire body of the forest.

Note – This article will be continued till the entire book is covered. Thereafter we will be formulating a summary of recommendations on how some of this information could be used for a training for children and youth on the life patterns of rainforests. We would be then sending out the training modules to the Forest Department of Sri Lanka after we publish it in this page.