Saturday Mar 07, 2026

Saturday Mar 07, 2026

Saturday, 22 April 2023 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Their religion was love. They were Muslims. One hundred percent they practiced the love preached in Islam

Their religion was love. They were Muslims. One hundred percent they practiced the love preached in Islam

The Love Religion

By Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad Rūmi

The inner space inside

that we call the heart

has become many different

living scenes and stories

A pasture for sleek gazelles,

A monastery for Christian monks,

A temple with Shiva dancing,

A kaaba for pilgrimage.

The tablets of Moses are there,

The Qur’an, the Vedas,

the sutras, and the gospels.

Love is the religion in me.

Whichever way love’s camel goes,

that way becomes my faith,

the source of beauty, and a light

of sacredness over everything.

The Wandering Kings

By Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad Rūmi

The king of Tabuk went on like this,

Praising Imra’u ‘I-Qays, and talking theology

and philosophy. Imra’u ‘I-Qay kept silent.

Then suddenly he leaned and whispered something

in the second king’s ear, and that second

king became a wanderer too.

They walked out of town hand in hand.

No royal belts, no thrones.

This is what love does and continues to do.

It tastes like honey to adults and milk to children.

Love is the last thirty pound bale.

When you load it on, the boat tips over.

So they wandered around China like birds pecking

At bits of grain. They rarely spoke because

of the dangerous seriousness of the secret they knew.

That love secret, spoken pleasantly, or in irritation,

severs a hundred thousand heads in one swing.

A love-lion grazes in the soul’s pasture,

while the scimitar of this secret approaches.

It is a killing better than any living.

All that world-power wants, really, is this weakness.

Love. Beloved. Death. Thirst. Intoxication. Eternity. Surrender.

These are some of the words that one may see in poetry of those such as Rumi, Hafez, Rabia of Basra, and Ibn Arabi; few of the many wandering mystics whose ode to God (Allah – the Beloved) were in poetry, the eternal language of love.

The sky was their roof and the desert sand was the golden carpet which they trod, oblivious to heat and sandstorms that could neither scorch nor blow away the love in their heart.

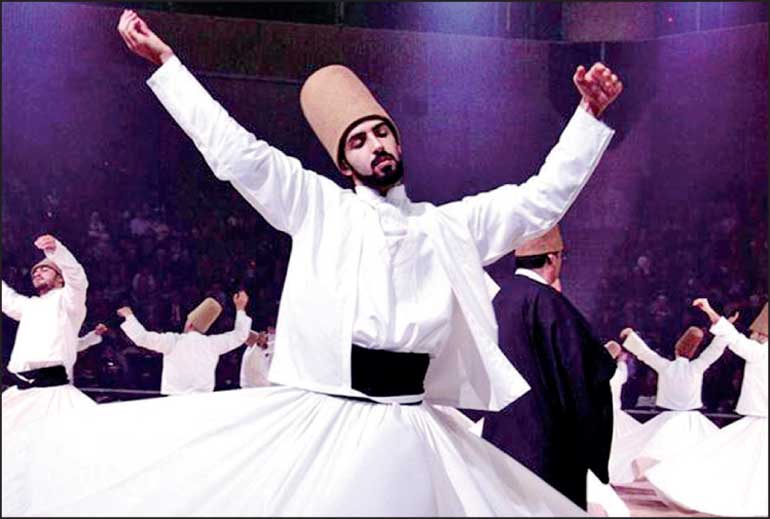

Their religion was love. They were Muslims. One hundred percent they practiced the love preached in Islam. Not for them were the harsher aspects of religion. They saw God in everything, everyone. They were lost to this world. Their world was the Beloved. The One. The One God. Allah. The ultimate reality which absorbed them. In holy love. They had renounced all else.

It is said they were the closest to the Prophet. They had left their homes. At least many of them. They lived in and around mosques. But mostly their prayer hall was the endless desert. They were called ‘Sufis’ because of the coarse cheap material known as ‘soof’ used by desert travellers which they wore. Not for them were the fine material donned by many. Their garment was love. Their prayer was love. They lived love.

One may, (if unfamiliar with Sufism) in reading some of the Sufi poetry think that this is mundane love poetry of the world. Yet, even for the uninitiated, it would be soon obvious that these are no ordinary love poems.

Some verses though would address more directly the love of God (Allah). For example the renowned female Sufi poet Rabia of Basra.

This short poem is a classic example.

If I Adore You

If I adore You out of fear of Hell, burn me in Hell!

If I adore you out of desire for Paradise,

Lock me out of Paradise.

But if I adore you for Yourself alone,

Do not deny to me Your eternal beauty.”

To write about Sufism and Sufi poetry may be one of the most wonderful tasks a writer could indulge in, but lack of newspaper space in this edition would make this writer restrict this yearning and limit to the core message. That Islam is a spiritual path of love.

Mewlana Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad Rūmi was originally from the Balkh region in the Eastern edge of the Persian Empire that is today Northern Afghanistan and he settled in Konya in South Central Turkey. He is probably the most globally well-known Sufi poet.

Coleman Barks, the American poet and scholar was the key figure responsible for taking the poetry and life of Rumi to the Western world and Barks in his many books such as ‘A year with Rumi,’ points out that when Rumi died in 1273, members of all religions, many being Christians (the wife of Rumi was known to be a Christian), came to the funeral.

Those who read Rumi may (or may not) know that the man who shifted Rumi from theology into poetry and mysticism was the most wondrous human being – the mystic Shams of Tabrizi. One could write reams on Shams of Tabrizi – (Iran) who irritated many frowning theologians who were suspicious of these ‘wanderers’ and their ‘preaching.’ Forty rules of Love is the most well-known surviving message of Shams.

Rule one goes as follows: How we see God is a direct reflection of how we see ourselves. If God brings to mind mostly fear and blame, it means there is too much fear and blame welled inside us. If we see God as full of love and compassion, so are we.

Rule two: The path to the Truth is a labour of the heart, not of the head. Make your heart your primary guide! Not your mind. Meet, challenge and ultimately prevail over your nafs (self, psyche, soul) with your heart. Knowing your ego will lead you to the knowledge of God.

Just these two rules alone, of the Forty Rules of Love as defined by Shams of Tabrizi, will show us how powerful an influence he would have had on young Rumi, who if he did not meet Shams may well have continued to be yet another theologian.

It is said that Shams came looking for just one person – a young religious scholar – Rumi – who he felt he was destined to preach Allah’s (the Beloved’s) love to, that Muslims so value.

This preaching was different to the scholars and the theologians of the time. It could be interpreted by some, if they were keen to see it as so, that the Sufi focus was deviating from Islam. This resulted in many of the Sufis being martyred.

For example one Sufi mystic was asked ‘Where is God,’ and he stated ‘Under my Feet.’ He was martyred. At first hearing, what he said may seem as blasphemy. However at a far different level, if God is up above, it is obvious that God is also down below as well!

One of the notable transitions from scholar, legal theorist, jurist and theologian to mystic was that of Al Ghazali who is respected as both Islamic law expert and mystic.

Below is the last verse written by Ghazali which was found under his pillow, composed the night before.

“Say to my friends, when they look upon me, dead,

Weeping for me and mourning me in sorrow,

‘Do not believe that this corpse you see is myself,

In the name of God, I tell you, it is not I,

I am a spirit, and this is naught but flesh,

It was my abode and my garment for a time.

I am a treasure, by a talisman kept hid,

Fashioned of dust, which served me as a shrine,

I am a pearl, which has left it’s shell deserted,

I am a bird, and this body was my cage,

Whence I have now flown forth and it is left as a token,

Praise to God, who hath now set me free,

And prepared for me my place in the highest of the Heavens,

Until today I was dead, though alive in your midst.

Now I live in truth, with the grave – clothes discarded.

Today I hold converse with the Saints above,

With no veil between, I see God face to face.

I look upon “Loh-i-Mahfuz” and there in I read,

Whatever was and is, and all that is to be.

Let my house fall in ruins, lay my cage in the ground,

Cast away the talisman, it is a token no more,

Lay aside my cloak, it was but my outer garment.

Place them all in the grave, let them be forgotten,

I have passed on my way and you are left behind,

Your place of abode was no dwelling place for me.

Think not that death is death, nay, it is life,

A life that surpasses all we could dream of here,

While in this world, here we are granted sleep,

Death is but sleep, sleep that shall be prolonged

Be not frightened when death draweth nigh,

It is but the departure for this blessed home,

Think of the mercy and love of your Lord,

Give thanks for His Grace and come without fear.

What I am now, even so shall you be,

For I know that you are even as I am,

The souls of all men come forth from God,

The bodies of all are compounded alike,

Good and evil, alike it was ours.

I give you now a message of good cheer

May God’s peace and joy forever more be yours.”

It is best that we end this short piece with this poem which is self-evident that the author of it lived his life as a dedication to a higher realm – devoted to Allah, and guided all his actions by this devotion. His actions in life towards others would thereby have been kind, merciful, empathetic because if God is merciful so should be his followers.

(SV)