Saturday Feb 28, 2026

Saturday Feb 28, 2026

Tuesday, 17 August 2021 01:12 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

For decades, Ceylon Tea was promoted as the cleanest tea in the world. In such a background, appropriateness of banning of importation of chemical fertilisers and pesticides used in production of tea is highly debatable – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

Investments in tea, current trends and unexpected future

Tea is a perennial crop. It is the major agricultural export income earner for our country.

Main stakeholders involved in tea in Sri Lanka are smallholder growers (owning less than 10 acres), small tea estate owners (owning 10-50 acre extents), corporate sector plantations, tea manufacturers in private, corporate, and state sectors, tea brokers, marketeers, exporters, banks and suppliers of engineering services, fertiliser, packing material, etc.

Additionally, many establishments such as banks, traders, etc. spread across the tea districts provide support services for the benefit of rural communities. Tea is the lifeblood of those communities.

All above stakeholders consider tea as a business and their physical and financial investments, rely heavily on their expectation of long-term sustainability and growth. Expected pay back periods of financial investments in the field and in factories are rarely less than five years, often well over 10 years. This point differentiates tea and other main plantation crops from most other businesses.

We, Sri Lanka Tea Factory Owners Association, are deeply concerned about the serious threat to medium to long term sustainability of our business as well as to our partner stakeholders, caused by the sudden decision to ban importation of chemical fertiliser and pesticides. We are in a serious dilemma.

Tea industry overview

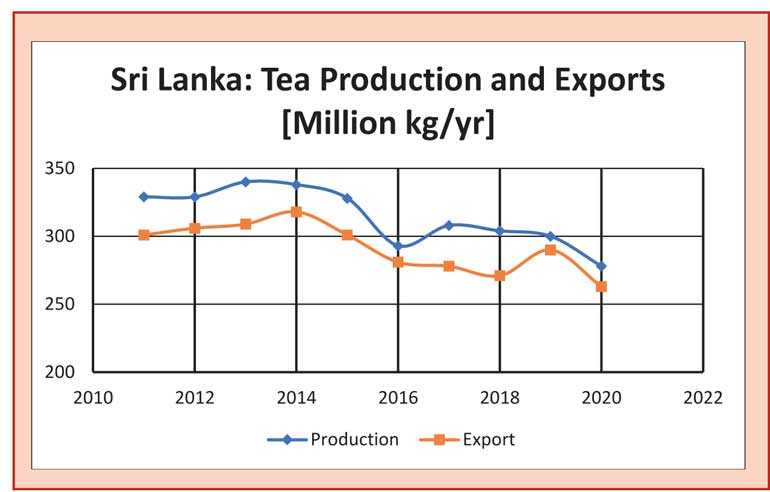

Globally, Sri Lanka is the fourth largest producer of tea. In 2013-2014, production peaked at 340 million kg and in the drought affected year 2020, production dropped to 278 million kg. Other than a small quantity of tea sold as private sales, bulk of the production is sold at the Colombo Tea Auction – the most dynamic tea auction in the world, conducted by Colombo Tea Traders Association. Export volume of tea peaked in 2014 at 317 million kg and recorded 263 million kg in the drought affected year 2020.

Tea is grown in 14 districts. Ratnapura, Galle, Matara, Kandy, Kalutara and Kegalle are districts where smallholder growers and private tea factories are predominant. While tea is cultivated in a total extent of 200,000 hectares, smallholder farmers cultivate 122,000 hectares, or 61% of the total. Total number of smallholdings is nearly 400,000. 51% of the smallholder extent is in small blocks of less than half hectare (Ref: Statistical Information on Plantation Crops 2018). It is therefore not an exaggeration to say that tea is the main income of a vast majority in these rural communities.

Of the total processed tea quantity, 75% was from leaf supplied by smallholders. While there are 650 operating tea factories in the country, 401 of them are privately owned, who process 66% of the total production, mostly depend on supply of green leaf from smallholders and small estate owners. 91% of tea produced in 2018 in Sri Lanka was of Orthodox variety for which Sri Lanka holds a prime position in the global supply.

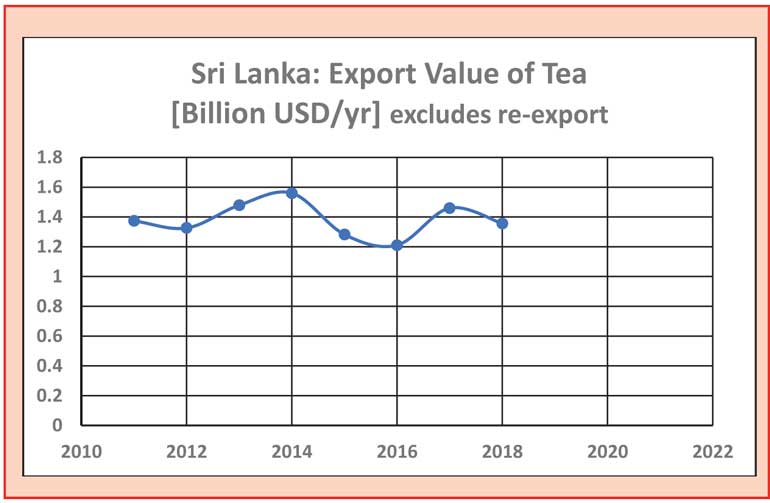

Export income from tea peaked in 2014 at $ 1.56 billion while it recorded $ 1.36 billion in 2018, excluding value of re-exported tea.

In 2018, Sri Lanka ranked third on export volume of tea (272,000 tons, mostly orthodox tea) behind Kenya (475,000 tons, mostly CTC tea) and China (365,000 tons, mostly green tea) and ahead of India (251,000 tons, mostly CTC tea). In terms of export value, among the large exporting countries, Sri Lanka ranked first at $ 4.98/kg, followed by China at $ 4.87/kg, India at $ 2.96/kg and Kenya at $ 2.93/kg.

For several decades, State has been continuously incentivising the development of the smallholder sector. In 2018, as subsidies, Rs. 560 million was distributed for replanting (75%), new planting (22%) and infilling/crop rehabilitation (3%). Tea fertiliser to smallholders was subsidised for many years.

Foreign input cost in production of tea is small compared to more celebrated garment sector. Main direct imported revenue components are, fertiliser, packing materials and pesticides whereas indirect components are electricity, diesel fuel, etc. and capital costs on machinery. In the total cost of production, the balance is the local cost which is a major portion. Primarily it is the human contribution and those related to abiotic factors. It is this human contribution that is challenged in the present unexpected scenario.

Projections and strategies – pre-April 2021

Prior to April 2021, all institutions responsible for the tea industry were planning increasing production volumes, increasing land productivity, and enhancing export income from tea. Strategies and action plans for the industry 2020-2025 initiated by the Ministry of Plantation Industries and formulated by a team of eminent experts with active participation of all stakeholder groups were aimed at achieving those aims.

While aiming to be the most competitive contributor to the national economy, it strategised to improve tea land productivity while sustaining soil fertility to double the tea export revenue generation by 2025, strengthen replanting and infilling programs in tea smallholder sector/ plantations and enhancing climate resilience in the tea industry. This action plan did not envisage a climate devoid of chemical fertiliser and pesticide use from the tea industry but kept focussed on improving efficiencies of use of inputs.

On the other hand, Global Tea Marketing campaign executed by the Sri Lanka Tea Board included not only strengthening the export markets but took a more holistic approach by promoting cultivation of tea.

Banning of import of chemical fertiliser and pesticides

Justification of banning of importation of chemical fertiliser and pesticides was the health-related issues faced by farmers as well as citizens at large. We have not seen any documented evidence relating health of tea workers and use of chemical fertiliser and pesticides. Recommendations on safe use of chemicals in cultivation of tea are well-documented and are easy to follow and easy to supervise.

Further, tea is immensely popular among local and foreign consumers as a healthy drink. For decades, Ceylon Tea was promoted as the cleanest tea in the world. In such a background, appropriateness of banning of importation of chemical fertilisers and pesticides used in production of tea is highly debatable.

Sri Lanka Tea Board has additionally taken the position that there is overuse of chemical fertiliser. According to Ministry of Plantation Industries, in 2018, a quantity of 166,000 tons of fertiliser was used by the whole tea industry. Whereas, according to a document now available in the social media, the estimated quantity of fertiliser required by the industry as per recommendation of the Tea Research Institute for 2021 is 199,000 tons. The statement that there is overuse of fertiliser does not therefore seem to have much merit.

Relationship between smallholder tea growers/estate owners and tea factory owners

There is a strong bond between the tea smallholder and the tea processing factory. It is a long-standing relationship based on mutual trust and recognition of the importance of the other party. Smallholders are the main supplier of green leaf to private tea factories. They in return get paid for leaf as per accepted system and in addition enjoy numerous benefits such as facilitation of knowledge transfer, pH testing and providing incidental cash and other needs.

Tea factories are in the best position to source fertiliser to the grower, because they have a clear idea of the requirement, both type of fertiliser as well as the quantity. Due to the bond between the two groups, factories often give fertiliser on one-to-three-month credit, a facility smallholder cannot get from any other party. Supply of fertiliser is at a regulated price. Some factories additionally deliver fertiliser at the doorstep of the grower. These arrangements, which are of mutual benefit do not get the mention it deserves.

Chemical fertiliser requirement

Types and quantities of fertiliser required to a tea field depends on the age of the plant, geographic area, etc. For example, time tested T65 mixture for nursery plants, T200 mixture for young plants and T750 mixture for immature clearings etc are all designed by years of experimentation by the TRI and overnight changes to hitherto unknown concoctions and methodologies may have serious effects.

For mature fields, where leaf is harvested at seven-day intervals, requirement depends on the potential yield and many other factors. Site specific fertiliser is clearly more desirable but is yet to find wide use in smallholder sector, not their fault, but due to lack of opportunities and facilities. Without use of chemical fertilisers providing nutrients in required quantities is a challenge beyond our imagination.

Organic cultivation of tea vs organic tea

Our understanding is that these are two quite different things. It appears to us that benefits of commercial scale organic cultivation of tea are over simplified. Mere non-use of chemical fertilisers and pesticides is what have been understood by many as organic cultivation. However, repercussions of non-use of chemical fertilisers in commercial scale cultivation of tea such as inevitable reduction on productivity, increase in cost of plucking, extending plucking rounds to keep the costs down, resulting reduction in quality of harvest and therefore quality of produce and lowering of price realisable for tea must all be considered before considering this massive change. It is naïve to expect enhanced profitability by mere organic cultivation of tea in commercial scale.

To get the price advantage, organically cultivated tea must be marketed as organic tea. There is no data on the size of the global organic tea market. Sri Lanka pioneered, organic tea cultivation and marketing in the eighties and the quantities produced remain exceedingly small even today. It is no doubt a niche market. Main reasons for lack of growth of the organic tea market, is the need to get at least three- or four-fold increase in price for the product to compensate for the increase in cost.

Now that is possible with tight scrutiny by certification systems, three to five years of ‘conversion period’ and demonstration of complete control of the environment of the total supply and production base. These are possible in small plots but highly unlikely in vast commercial sale tea cultivation systems.

Most certified organic tea production units in Sri Lanka have been tried out in rather low productive lands/estates where normal tea production is not profitable at all. Due to high investment required for replanting, they have resorted to organic cultivation. Most these units, by private estate owners and plantation companies have after many years of effort have given up. There are only a few success stories, with considerable patience and ability to absorb losses over many seasons, they have spent considerable resources in marketing in carefully selected markets.

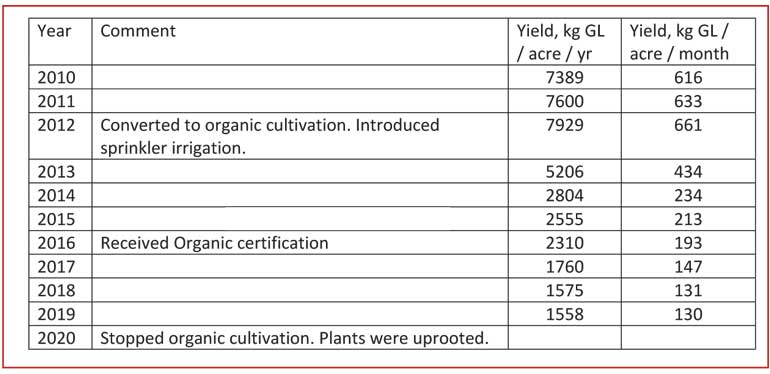

We are aware of an effort by one of our members – a winner of national plantation awards 2012, who converted a high yielding 10-year-old VP field to organic cultivation. Results are given below.

Though increase in prices for few grades have been enjoyed, other grades were not attracting any enhanced price. The overall revenue income had been totally inadequate to continue the project. This is the tragic truth.

Inputs for organic cultivation of tea

It is imperative that Sri Lanka should continue to work towards enhancing production and productivity and not imagine the opposite as a viable option. It is in such a scenario that we look at the nutrient requirement for cultivation of tea. Urea is the main Nitrogen source for mature tea fields. Its Nitrogen content is 46%. Providing required Nitrogen by way of non-chemical fertilisers such as compost is an exceedingly difficult task.

Nitrogen content of compost from leafy material is about 1% and that of animal manure is little higher, poultry manure having 4% Nitrogen. No doubt organic compounds are particularly useful as a way of improving the fertility of soil and thereby more efficient use of nutrients. There is no argument in that, but its role as a nutrient supply must be accepted as exceedingly limited.

Alternatively, one may talk of organic fertilisers with higher Nitrogen content. But then that be with unknown compositions of undesirable material and far too risky a preposition for use by the tea industry. This can also create issues in marketing our tea. During last three months, many experts have pointed out the risks in using high Nitrogen organic fertilisers made from undeclared processes and having unknown composition. It is our view that any high Nitrogen organic fertiliser should strictly satisfy SLS 1704:2021 standard.

Many other suggestions have been discussed during numerous Zoom webinars held recently. Biochar, Bio-Film-Bio-Fertilisers, wormy technology, moves away from monocropping, etc. All these are fine, once researched and demonstrated so that farmer can make use of these new ideas judiciously with conviction.

Many university dons and experts in the field of agriculture have voiced their views and agree on the need to improve fertility of lands and possible role of organic material but continued to point out the limitations in the exclusive use of organic material in commercial cultivation of tea, particularly negative effect on yield and thereby sustainability of the business.

Second half of 2021

With stocks of chemical fertiliser available with suppliers, if the distribution is organised in a fair manner, most growers will get some quantity. Whether that is adequate or not remains an unknown. Due to unavailability of nutrients, already there are signs of lowering of quality of harvest. By the end of 2021, best one could expect is only a small reduction on the annual production.

But the real effect of the ban will be seen only in 2022.

During these few weeks, we have witnessed mushrooming of compost suppliers. In the absence of any quality assurance, unsuspecting growers can easily fall prey to these suppliers.

With decades of commitment and effort, exporters of Ceylon Tea have developed stable markets world over. If the supply of tea were to reduce by a noticeable extent, there is a real possibility of Sri Lanka losing these established markets to our competitor countries, India, Kenya, Vietnam, etc. Our exporters have clearly pointed out this scenario. This is not a view to be brushed aside.

Our proposals

With the aim of sustaining the tea industry, ensuring livelihood of its stakeholders and their families, particularly the smallholder growers, preventing closure of some tea factory operations, preventing loss of markets for Ceylon Tea and preventing erosion of export income from tea, we propose the following.

Promote of soil fertility improvement activities in all tea districts. Use funds allocated for subsidising tea fertiliser for this purpose.

Provide knowledge on generating raw material required for large scale in situ compost making and infuse new technologies to grass root level.

Promote growing of leguminous trees such as Gliricidia, Crotalaria, etc. in all tea districts.

Do not import organic fertiliser in whatever name and style. Experts have pointed out associated dangers.

In order not to deceive the unsuspecting growers, create a method to assure quality of locally available compost.

Reverse the ban of import of fertiliser and pesticides required at least for the tea industry – By that action tea industry can continue to be the most reliable net foreign exchange earning industry.

Ensure strict quality control of fertiliser as per SLS standards, irrespective of imported or locally produced, so that there is minimum risk of undesirable contaminants coming in to the production process.

Promote research and development activities focussing on minimising losses of applied nutrients.

Ensure strict quantity control of pesticides used in commercial tea cultivation.

Take all actions to prevent availability of illegally imported pesticides in the country.

To prevent severe impact on the tea industry from the effects of banning of importation of chemical fertilisers and pesticides and the resulting drastic effect on the livelihood of several millions of people who consider tea as their main source of income and significant loss to the national economy, we urge authorities to implement the above proposals.

As Sri Lankans it is our duty to save the tea industry – the steadiest net foreign earner to the country.