Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday, 8 April 2022 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Rijksmuseum

Lewke Disave's cannon

Inscription found on Lewke Disave's cannon

An intense joint international provenance research dispels mythmaking and ambiguity which encircled six distinct royal Kandyan objects for centuries, which are displayed in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam

By Randima Attygalle

In a recently concluded collaborative international provenance research, six Sri Lankan objects from the Rijksmuseum collection were confirmed to be of Lankan origin. A golden and a silver kasthãné (sabre) a golden knife, two maha thuwakku (wall guns) and Lewke Disave’s cannon-all belonging to the Kandyan kingdom, now found in the Rijksmuseum collection mirror the dexterity of the Kandyan craftsman.

The international joint provenance research which represented researchers from Sri Lanka, the UK, the US and the Netherlands including the Rijksmuseum Conservation and Science Department has shed new light on the colonial artefacts found in the Dutch museums. The laborious research has also dismissed myth-making and conflicting-views which shrouded the artefacts for centuries and thereby allowed to rediscover the authenticity of them.

A landmark research

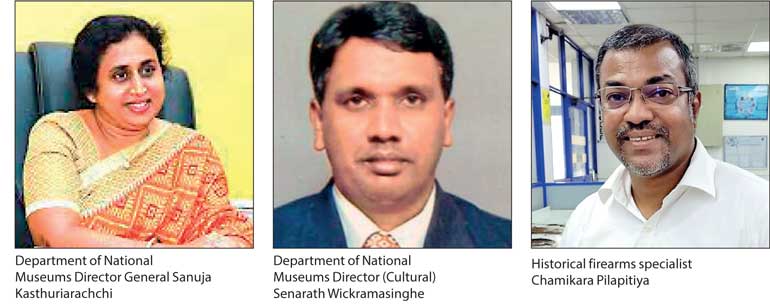

The joint research which was carried out under the Pilot project Provenance Research on Objects of the Colonial era (PPROCE) of the Rijksmuseum is another landmark in Sri Lanka provenance studies, points out Sanuja Kasthuriarachchi, Director General of Department of National Museums. “Since the Provenance Report of Dr. P.H.D.H. de Silva, the director of the National Museum in Colombo in the 70s, (Antiquities and Other Cultural Objects from Sri Lanka (Ceylon) and Abroad), very little notice was taken of the Kandyan objects in discussion until this recent intense study,” says Kasthuriarachchi.

The contemporary conviction of many of the colonists including the Netherlands that the looted objects of their onetime subjects should be returned to their country of origin has led to the pilot project which extends to 40 Indonesian objects as well.

Ornamented kasthanes

Scores of historical documents, Dutch records, art and craftsmanship of objects in study, their artistic value, technology and chemical composition were among the criteria adopted by the experts in determining the provenance of the Kandyan objects, explained Senarath Wickramasinghe, Director, (Cultural), Department of National Museums who was among the researchers of the provenance study. The highly ornamented golden kastane or the sabre embellished with 136 diamonds and 13 rubies is confirmed to have been a personal belonging of King Kirthi Sri Rajasinha (r.1747-1782). It has a massive golden hilt shaped with four lion heads (sinhas) and goddesses Lakshmi and Saraswati.

determining the provenance of the Kandyan objects, explained Senarath Wickramasinghe, Director, (Cultural), Department of National Museums who was among the researchers of the provenance study. The highly ornamented golden kastane or the sabre embellished with 136 diamonds and 13 rubies is confirmed to have been a personal belonging of King Kirthi Sri Rajasinha (r.1747-1782). It has a massive golden hilt shaped with four lion heads (sinhas) and goddesses Lakshmi and Saraswati.

“This kastane is most likely to have arrived in the collection of the Dutch Stadtholder (the chief magistrate of the United Provinces of the Netherlands from the 15th to the late 18th century) before 1795 and was first recorded in 1816.”

“We have found no documentation of the transfer of this object by any of the heirs of Van Eck to the collection of the Stadtholder. Moreover, there is also no evidence found at all that could suggest another provenance. Neither the route the kasthãné took from Kandy into the collection of the Dutch Stadtholders nor the exact moment of its arrival in the collection simply remained unrecorded,” explains Wickramasinghe, the co-author of Ancient Swords, Daggers and Knives in Sri Lankan Museums. He goes on to explain that the object analysis indicates that this kasthãné was made in the royal workshops of the Kandyan kingdom known as pattal hatara.

Kandyan-Dutch war

The kasthãné is presented in the Rijksmuseum as spoils of war, obtained by the VOC during the siege of the palace of Kandy in 1765 when large scale looting of Kandyan objects took place. Following the Dutch East India Company (VOC) army attack on the palace and Temple of the Tooth Relic (Dalada Maligawa) in Kandy, royals, inhabitants, and the Kandyan soldiers left the city. The historical sources have it that the Dutch troops had found the warehouses partly emptied by the retreating Kandyan troops, who were allowed to do so by the king.

The looting that followed spread from the warehouses even to the apartments of the king himself, even though VOC Governor Lubbert Jan van Eck had explicitly prohibited this. Several objects from this Kandyan-Dutch war circulated in the country as well as in the Netherlands in the decades after the war. Still, a great deal of the plunder was eventually sold or left behind by the soldiers in Kandy or during their trip back to Colombo after the retreat of the troops from Kandy at the end of August 1765 as history sources confirm.

In the 19th and early 20th century, however, the Kandyan provenance was forgotten and the gold mounted kasthãné was described as Javanese as late as 1957. Since 1965 the kasthãné has been presented as spoils of the Dutch-Kandyan war.

Mistaken identities

Another similarly ornamented kasthãné with a silver hilt shaped with four lion heads is also exhibited in the Rijksmuseum and presented as spoils of war, obtained by the VOC during the war with Kandy in 1765. “Its shape and ornaments are typical for kasthãné from the Kandyan Kingdom in the 18th century. It too was made in the Royal workshop and was probably meant for a member of the Kandyan aristocracy,” points out Wickramasinghe.

aristocracy,” points out Wickramasinghe.

Although the route the kasthane took from Kandy to Netherlands is not clear, there is no evidence found that would suggest a different origin, remarks the expert on ancient swords, daggers and knives. Until 1937, this highly decorated Kandyan artefact was described by the Dutch authorities to be originating from the mainland of Southeast Asia.

Sporting a crystal hilt and iron blade, which are partly decorated with gold and its wooden sheath entirely overlaid with gold, the intricately crafted knife which was among the six objects of study reflects the dexterity of the signature 18th century Kandyan workmanship. “The knife’s elaborate decorations confirm that this tool was produced in one of the royal workshops of the Kandyan king and also formed part of the royal garb,” noted its researcher, Wickramasinghe. Another looted object during the siege of the Kandyan palace, in the 19th and early 20th century the Kandyan provenance was forgotten, and the knife was understood as a ‘Malay dagger’. Since 1965 it has been connected to the spoils of the Dutch-Kandyan war by the Rijksmuseum and other researchers.

Cutting-edge technology of Sri Lankan guns

The provenance study on the two wall guns which translated into maha thuwakku in the vernacular during the Kandyan times was done in collaboration with the historical firearms specialist and the author of several books on the Kandyan period, Chamikara Pilapitiya who came on board on invitation by the Colombo National Museum. His research unearths new knowledge about the cutting-edge technology claimed by the Kandyan designer of weapons. The arms, replete with woodwork and engraved motifs which are recognisable as Kandyan, represent a unique and early Sri Lankan tradition in gun making and warfare.

The two wall guns, each weighing 28kg, are unique examples of mobile, heavy artillery that the troops of the Kandyan king used to defend the city and palace. The wall guns had to be mounted on a tripod before being fired. “The firing mechanism of these two guns is flintlock, known as bondikula by the locals. This mechanism is fitted on the left side with an external safety catch which is unique to the guns of Sri Lankan origin. The guns are designed to be fired with the butt stock resting from the chest to the shoulder, rather than on the shoulder, which is a unique characteristic of guns of Sri Lankan origin,” explains Pilapitiya.

Another significant feature of these two guns is the ‘detachable pan’ which the expert argues to be typical to the Sri Lankan maha thuwakku, and very rare in guns of other origins. “The detachable pan is made in the form of a slide, consisting of a pan, touch hole, and a slot to which a clip is fixed in order to prevent the movement of the slide. All of these, excluding the clip, are one unit.”

An age-old tradition of firearms

One of the most interesting features of the maha thuwakku as Chamikara Pilapitiya emphasises is that of the cross head screw. He explains that the unique feature of these crosshead screws is that it has been only used in points where high torque is used, such as to secure the lock plates to the stock. The firearms specialist goes onto note that crosshead screws on Sri Lankan guns date back to 1680 A.D. “The provenance study underscores the innovation and skill of the ancient Sri Lankan,” observes Pilapitiya who cites the texture of the steel which was used for the production and also the jaw screw. He emphasises that when measuring the thread of the screw it is apparent that no modern thread fitted exactly right.

“Until now, very little notice has been taken of the two guns, and as far as we know it was only in 1975 that one of the two guns was described as Kandyan by Dr. P.H.D.H. de Silva in his study. However, no explicit connection to the Kandyan-Dutch war was made at the time,” says Pilapitiya.

He concludes that maha thuwakku were taken from Kandy during the siege in 1765 and sent from Colombo to Batavia after the war, and subsequently sent from Batavia to the stadtholder as a gift, together with two other large guns, (forming a set of four) which have been identified as NG-NM-515 and NG-NM-516. He also recommends further research into the provenance and material aspects of the other two guns.

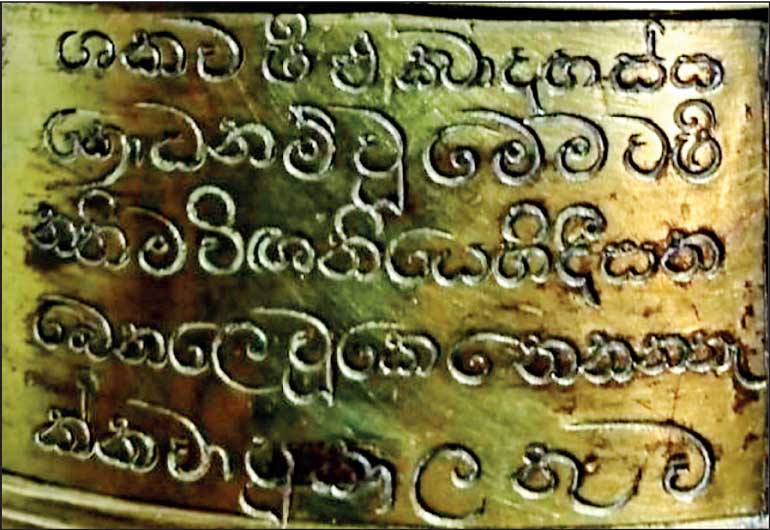

Lewke Disave’s cannon

Richly ornamented with silver, gold and gemstones, Lewke Disave’s cannon has floated many theories of its origin since its arrival in the Netherlands. The small bronze ornamental cannon embellished with Kandyan motifs such as liyawel, kalpa vrukshaya and nari lata, bears an inscription which claims Kandyan aristocrat Leweke Disave to be the donator of the cannon. Although it does not specifically mention to whom it was donated, the research findings confirm that the nobleman has gifted it to King Sri Vijajaya Rajasinghe who ruled Kandy from 1739 to 1747.The cannon interestingly carries a shield which resembles the Kandyan Royal monogram.

The object analysis reveals that the cannon was manufactured in a foundry in Batavia or the Netherlands as a gift for, or on order of, the King of Kandy at an unknown date. In 1745 Lewke Disave added the exquisite decoration on the cannon as a gift for the King Sri Vijajaya Rajasinghe. It is also recorded by the Dutch as war booty in 1765, after the Dutch siege and destruction of the palace of Kandy. In 1766 the cannon served once more as a gift, this time from the Dutch governor Lubbert Jan van Eck of Ceylon to the guardian of the Dutch Stadtholder Duke Louis Ernest of Brunswick-Lüneburg. After its arrival in the Netherlands, it was presented as a war trophy in the Cabinet of Curiosities of the Dutch Stadtholder Willem V.

Shrouded in mystery

The inscription of the cannon has been subject to various interpretations and one of the main controversies was whether Lewke gifted the cannon to the Dutch or whether the Dutch had taken the cannon as war booty during the Kandyan-Dutch war. For some time in the 19th century, it was considered to be part of the legacy of the Dutch national hero Michiel de Ruyter. The discovery of two very similar cannons in Windsor castle formed a turning point in the reconstruction of the cannon’s early history. It was only around the 1880s that the Sri Lankan origin of the cannon was rediscovered and in 1894 the inscription was translated from Sinhala to English for the first time.

The provenance research report drawn by our local scholars Prof. Asoka de Zoysa and Dr. Ganga Dissanayake (from the University of Kelaniya) together with Ruth Brown and Kay Smith from the UK and Arie Pappot from the Netherlands explicitly dismiss the thesis that Lewke Disave had gifted the cannon to the Dutch Stadtholder. The archive for the VOC for the period around 1745/6 does not mention the presence of a small, decorated cannon or something similar which further reinforced the researchers’ view that it was Lewke’s cannon mentioned in the VOC records as war spoils.

Sri Lankan cultural symbols

The laborious provenance research which has led to the dispelling of many myths and ambiguities that shrouded our Kandyan artefacts also call for rediscovery of these lost ornaments. These cultural symbols which mirror the cleverness of Sri Lankan artisans of yesteryear are yet to see reclaiming their due pride of place in their land of birth. “We earnestly hope that these objects will be returned to us, and a gesture of that nature will no doubt solidify the diplomatic relations between the Netherlands and Sri Lanka,” observes the DG of Department of National Museums who goes on to add that this research drives all Sri Lankans to take pride in the skill and the aesthetic taste of our ancestors.

The museum official also extends her thanks to Tanja Gonggrijp, Ambassador of Netherlands to Sri Lanka, Taco Dibbits, General Director Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Dr. Hanna Pennock, Senior Advisor Cultural Heritage Agency of the Ministry of Culture and Science in Netherlands, Martine Gosselink, General Director of the Mauritshuis, Hague who facilitated the joint research and Dutch researchers - Dr. Alicia Schrikker and Doreen van den Boogaart who contributed to make the research a fruitful one.