Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Wednesday, 1 October 2025 00:30 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

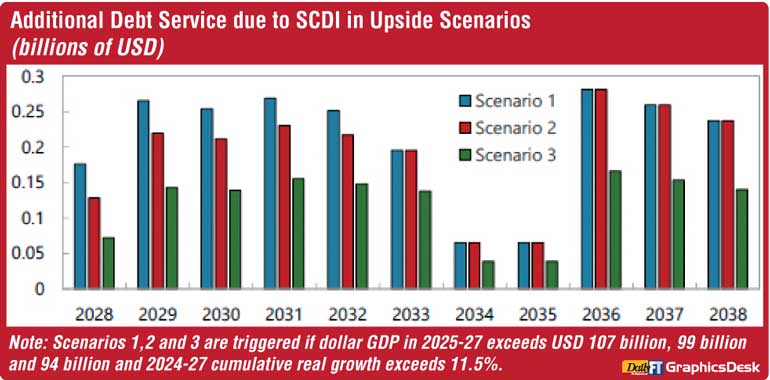

Sri Lanka could face additional debt service payments of between $ 150 million and $ 270 million a year from 2028 if its economy grows faster than projected, according to the IMF. Payments would continue until 2038 and are capped at around $ 250 million annually.

“In the case of Sri Lanka, the one-time adjustment nature of the macro-linked bonds presents risks to Sri Lanka as higher payments after 2028, once triggered, would persist even if economic performance were to deteriorate thereafter,” the IMF said in September 2025 working paper titled ‘Sri Lanka’s Sovereign

Debt Restructuring: Lessons from Complex Processes’.

The extra payments depend on GDP outcomes between 2025 and 2027.

“Scenarios 1, 2, and 3 are triggered if dollar GDP in 2025–27 exceeds $ 107 billion, $ 99 billion and $ 94 billion, and 2024–27 cumulative real growth exceeds 11.5%,” the report explained.

Once these thresholds are met, higher payments become permanent for a decade regardless of what happens to growth later.

The IMF noted that State-contingent debt treatments helped address concerns about macroeconomic uncertainties, but designing them prudently was important.

These instruments, known as State-Contingent Debt Instruments (SCDIs), link a country’s payments to its economic performance.

They have been used in Argentina, Greece and Ukraine to bridge differences between debtors and creditors by allowing creditors to trade lower upfront recovery for potential higher future payments.

In Sri Lanka, however, SCDIs constituted a core part of creditors’ recovery and prolonged the negotiations due to their complexity.

“They can introduce political complications in the future in case higher payments are triggered but are not socially accepted” the Staff Report said.

While the Fund does not get involved in the details of the instruments’ design in specific cases (this is an issue for the authorities, their creditors, and respective legal and financial advisers), the Fund needs to assess the impact of these instruments on program goals, i.e., the restoration of macroeconomic and debt sustainability,” it added.

The IMF does not design these instruments itself but stressed it must evaluate their impact on debt sustainability.

This includes assessing whether the extra payments make it more likely that debt targets are breached, whether different groups of creditors are treated fairly, and whether design risks such as uncapped exposures or poorly chosen triggers could undermine repayment capacity.

The Fund explained that these assessments involve “complex modelling under the SRDSF framework, which informs the extent to which upside risks can be shared with creditors without compromising debt sustainability.”

The SRDSF, or Sovereign Risk and Debt Sustainability Framework, uses fan charts based on past economic data to simulate thousands of possible outcomes for debt and financing needs.

The IMF then tests whether adding the SCDIs would increase the probability of crossing debt safety thresholds, worsen debt in bad economic scenarios, or create excessive risks in extreme cases.

According to the IMF, Sri Lanka’s arrangement met these conditions. The probability of breaching debt-to-GDP and gross financing needs targets was within acceptable limits.

In scenarios where financing needs were already too high, the SCDIs did not make them worse compared to standard bonds.

The report also noted that “the 90th percentile contributions to average GFNs were below 0.4% of GDP,” meaning even in the most adverse 10% of outcomes, the additional burden was still relatively small. Payments were also capped at $ 250 million per year.

Even so, the Fund cautioned that “some risks remain as no methodology can perfectly capture such complex uncertainties.”