Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Thursday, 30 November 2023 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

From left: MMCA Sri Lanka Assistant Curator Thinal Sajeewa, Chief Curator Sharmini Pereira, and Assistant Curator Ritchell Marcelline

|

Endorsed by the World Monuments Fund, a first for Sri Lanka, ‘88 Acres’, the latest exhibition by the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art Sri Lanka (MMCA) resurrects the Watapuluwa Housing Scheme in Kandy, a forgotten watershed in the contemporary history of Sri Lanka that heralded a new form of social housing here at home. ‘88 Acres’ explores how this sprawling hillside development completed in 1958, was ahead of its time in providing affordable accommodation for a diverse ethno-religious community of public servants in Sri Lanka. The exercise is also a celebration of its unsung designer Minnette de Silva, Sri Lanka’s first woman architect, the first Asian woman to be elected an Associate of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) and one of the two women in the world at that time to have an architecture practice in her own name

By Randima Attygalle

|

| Minnette de Silva - an unsung pioneer |

|

| Sharmini Pereira

|

“The Second World War was raging, the world was broken and the cold war was beginning to take shape. Amid conversations revolving around all this was a phenomenal woman, wanting to be a professional architect when all that was expected of a woman then was to be a mother and a wife,” reflects MMCA’s chief curator, Sharmini Pereira. Sharmini says choosing Minnette de Silva as the subject for MMCA’s latest artistic labour was “easy and the most natural choice” under a solo architectural segment, the first such effort by MMCA. Yet, with Spartan original material except for the architect’s monograph, studying her work was a huge challenge.

“There were no original drawings or models of Minnette’s and the primary source of information was her monograph, ‘The life and work of an Asian woman architect’ published a couple of months after her death in 1998. In this, there is a small chapter on the Watapuluwa Housing Scheme that was pioneering and ahead of its time. As with our previous exhibitions on artists, we wanted to look at a particular effort in detail and the same thinking was replicated with Minnette by looking at one of her landmarks,” notes MMCA’s chief curator.

Minette’s transnational world

Born to George E De Silva, lawyer and politician of independent Ceylon and Agnes Nell, a suffragette and an art enthusiast, Minnette was avant-garde, rebelling to pursue a vocation unheard of for a woman then. Despite her father’s opposition, Minnette pursued her vocation, moving first to Mumbai and later postwar London to study.

After Sri Lanka became independent in 1948, De Silva returned and set up a studio in her family home “St George’s” on George E De Silva Mawatha, and became one of only two women in the world then to establish an architectural practice in her own name. As architect and writer David Robson would note, ‘Minnette was a woman operating in what was still a man’s profession within a chauvinist society.’

Amie Corry, a London-based writer and editor notes in her documentation of Minnette in ‘Gagosian Quarterly’: ‘While De Silva’s practice was contained in her homeland, her world was transnational. She travelled widely, fostering connections with the likes of Pablo Picasso, Henri Cartier-Bresson, and Jawaharlal Nehru and developing a close relationship with Le Corbusier, the feted pioneer of modern architecture. Throughout their decades-long correspondence, Le Corbusier, who addressed De Silva as his ‘small bird of the islands,’ made evident a deeply felt respect, as well as affection, for the younger architect.’ MMCA’s ’88 Acres’ is also a means of augmenting international research on Minnette as its chief curator remarks. “The endorsement that comes from the World Monuments Fund is a huge celebration and an ideological shift towards Sri Lanka’s first female architect.”

To understand Minnette is to understand her at two levels: when she actively worked, and projecting her work to present times, reflects Sharmini. “Minnette grew up with two empowered parents in a setting where political consciousness was developed very early. She moved around in certain political and social circles probably because of the status of her family which gave her access to the world at large. It was true in the case of all those who came from affluent families at that time. But what matters is what they did with those opportunities. In Minnette’s case and even her sister Anil’s (Anil de Silva- Vigier) who was an art historian and author, what they did at that time was absolutely phenomenal.”

Participatory approach in housing

Kandy in the 1950s was densely populated and was home to many government servants. However, the lack of private housing drove them to live in dire conditions. In 1954 the Kandy Housewives’ Welfare Association was launched to address the issues of the increasing cost of living and the lack of adequate housing. The initiative became a forerunner to the formation of the Kandy Public Servants’ Building Society in 1954. The Society made successful representation to the then Government to acquire 88 acres of the Hancock Estate at Watapuluwa to establish a ‘Housing Scheme’ – a term then unheard of here at home.

The project, as Dr. Chanaka Talpahewa in his writing, ‘Towards housing for all through people’s participatory process,’ notes, ‘went on to shape the national policy on public housing when Lorna Wright (a member of the Kandy Public Servants’ Building Society Director Board) convinced the National Housing Commissioner, L.V. Wirasinha and Minister Vaithianathan, for special dispensation to obtain a salary loan to buy land and build their own homes for the Kandy Kachcheri public servants which was then not provided for. Wright’s successful argument was as to why a two-year salary loan for land and housing cannot be considered if the Financial Regulations permit loans for purchase of vehicles. Today, public servants’ housing loans have become a Government policy.’

Sri Lanka’s first Government Public Servants’ Housing Scheme commenced in June 1955 with the participation of the then Housing Minister, and Minnette de Silva who herself hailed from Kandy, was appointed the architect of the project. ‘The most remarkable pioneering example of a participatory approach witnessed in Sri Lanka was the planning and the execution of the Watapuluwa Housing Scheme Project’, writes Dr. Talpahewa who goes on to state that ‘it was a trailblazing and innovative project, decades ahead of its time. For the first time in Sri Lanka, and perhaps in the world, an inclusive beneficiary participatory process/approach was adopted in housing.’

The Watapuluwa Housing Scheme as the writer further notes, ‘is a unique Sri Lankan experience and stands out as an epitome of qualities we recognise in social housing such as economy and efficiency of delivery, sensitivity to location, fusing modernist principles with traditional local craftsmanship, conserving the environment (including climate change issues), giving emphasis to greenery, focusing on DRR, collaborating with the beneficiary (inclusivity) in the designing and construction, utilisation of local labour, etc.’

A unique feature of the Watapuluwa Housing Scheme is that, unlike standardised mass houses in today’s Housing Schemes, no two houses are alike. Further to a preliminary questionnaire Minnette gave the beneficiaries, she went further to develop another to determine the socio-cultural status of them. Subsequently, Minnette developed five or more type plans to suit the topography of each site with six or more sub-types to suit the cost and wishes of each member accounting to a total variation of around 50 sub-types together with community amenities such as nursery school, clinic, park, etc. True to her trademark of exploiting local materials, Minnette assured that traditional material was used in construction as much as possible.

|

Through the eyes of artists

Most of Minnette’s buildings, all together 40, are unheard of today, some demolished or altered beyond recognition, while just a handful remain in their original form. The Watapuluwa Scheme, one of her landmarks, remains little heard of today. In a bid to rediscover this pioneering example, MMCA in 2020 commissioned three gifted contemporary artists- Irushi Tennekoon, Sumedha Kelegama and Sumudu Athukorala to produce a film in which the groundbreaking housing scheme is revisited 65 years later to enable insights into Minnette’s influences and the challenges her design-approach entailed. The trio’s second engagement with MMCA following their first- 83’- A Very Short Film’, visual documenting on the Watapuluwa Scheme was a challenging undertaking as Sharmini observes. “It was a voyage of discovery for them as it was for us, with bare minimum information to go by,” says Sharmini who applauds Irushi, Sumedha and Sumudu for the final product, the fruit of almost three-years of hard work. “It was at the height of the pandemic when the preliminary work was done and they had to navigate multiple challenges in travelling and later on building relationships with the residents of Watapuluwa.”

The artists were also inspired by the expertise offered by Forensic Architecture- a British agency that employs architectural techniques and technologies to investigate cases of state violence and violations of human rights around the world. “They use the practice of architecture not to build designs, but to think about reconstruction of events that take place where there is a lack of evidence needed to be presented in courts of law. We turned to them because our situation was somewhat similar to the predicament of not having an original or an artefact. It was enlightening to see them creating stories, narratives, through this approach where there was a lack of evidence. The artists employed the technique of witness testimonies and spoke to different kinds of people, and used the video testimonies in their work of art. They studied different kinds of mapping as well,” recounts Sharmini.

The one-hour film, that is the central point of the exhibition, will play on the hour from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m (8 viewings per day) throughout the exhibition that extends to July next year.

Animation as a tool

For artist and animator, Irushi Tennekoon of ‘Animate Her’ fame, where several trailblazing Sri Lankan women left their footprint in their chosen vocations were animated by her, Minnette de Silva’s animation in the film was a totally different experience. “In the case of all the other women I animated, I could set a mike and listen to them narrating their stories. I was therefore able to include their voice in the films. Whereas, with Minnette, I wasn’t conversant with her work nor her influence until I embarked on this project,” says Irushi who considers it a great honour, along with her two team members to have been commissioned to talk about someone as important as Minnette who is underappreciated. Irushi explains animation is used in the film to bridge the gap of knowledge and bring the great architect to life. “Stories, interviews with various people who knew her in life, help us imagine what she would have been and we did around 40 interviews to piece this puzzle together and animation has helped us bridge gaps.”

Contemporary histories are often forgotten and at times deliberately, reflects Irushi who believes that it is the role of the artists to bring those histories back to life. “It is not the role of the government or institutions only but having the support of these partners is critical for artists to lend voice to forgotten histories and personalities. In terms of this project, if not for the backing of MMCA and the support of the British Council, we would not have been as successful as we were. Their backing opened many doors for us to go and reach out to friends and family of Minnette, top architects and other industry experts in the field,” recollects Irushi who finds the whole exercise a rewarding experience.

Modern regionalism

The Watapuluwa Housing Scheme was nothing but a “spectacular feat” of the time, notes Sumedha Kelegama. An architect by profession, Sumedha notes that the scheme is a reflection of ‘regionalism’ championed by Minnette. “Although some of the original dwellings have been altered, the stone exteriors, the shape of roofs still reflect the unmistakable Minnette de Silva’s stamp.” The scheme with around 230 houses spread across 88 acres, were personalised by their designer, unlike the ‘cookie-cutter type’ obvious in similar schemes, says the architect. The beneficiaries were given a choice between a carport and a garage for example.

“Minnette was a strong believer of the region- she was at all times conscious as to how a modern social person should live in a house in the context of the region. She achieved this in her fusion of modernism with native arts and crafts,” explains Sumedha, noting that Minnette advocated regionalism long before the western world started a discourse about the concept. “In her book, Minnette writes that she was influenced by greats such as Le Corbusier and Patrick Geddes who created this balance for her to come up with ideas on regionalism,” says the architect.

Applauding Sharmini’s pick of a solo project of the unsung architect as opposed to a repertoire of her work, Sumedha remarks: “this labour helped us study a forgotten architectural landmark in the country in great detail. We wanted to forget all the mainstream narratives about Minnette, the fact that she was associated with big names, the fact that she was forgotten by the world, etc. Instead, our focus was only her great work.”

An architect by profession and a Minnette de Silva enthusiast, Sumudu Athukorala says her brilliance was hardly a point of discussion during their undergraduate days. “Compared to other notable names, Minnette was referred to only in passing. It is only through this project that we came to know the real depth of her work. Knowing of other factors in the evolution of architecture in the last 150 years, we realise today the magnitude of her influence in this journey of evolving,” says Sumudu. Speaking to some of the first generation owners of the scheme and other Watapuluwa folk who knew Minnette and had anecdotes to share was also an exhilarating experience, says Sumudu.

Experimenting with indigenous methods such as wattle and daub, and incorporating rammed earth technology, a process popularly used for today’s ecohomes, Minnette also saw to it that skilled craftsmen from the backwaters are given a chance. “For all De Silva’s vision, her contribution to architecture has been only belatedly and sometimes begrudgingly acknowledged,” writes Shiromi Pinto (Minnette de Silva: the brilliant female architect forgotten by history) who authored ‘Plastic Emotions’, based on the architect’s life. Despite her international reputation, she was never invited to teach in Colombo. The Sri Lanka Institute of Architects awarded her its Gold Medal only in 1996, just two years before her death at the age of 80.

Experimenting with indigenous methods such as wattle and daub, and incorporating rammed earth technology, a process popularly used for today’s ecohomes, Minnette also saw to it that skilled craftsmen from the backwaters are given a chance. “For all De Silva’s vision, her contribution to architecture has been only belatedly and sometimes begrudgingly acknowledged,” writes Shiromi Pinto (Minnette de Silva: the brilliant female architect forgotten by history) who authored ‘Plastic Emotions’, based on the architect’s life. Despite her international reputation, she was never invited to teach in Colombo. The Sri Lanka Institute of Architects awarded her its Gold Medal only in 1996, just two years before her death at the age of 80.

Wearing flowers in her hair and navigating scaffoldings draped in saree, Minnette was a woman unapologetically herself. 88 Acres’ is a must-see for any Sri Lankan to be inspired by this table-turning Lankan profession who took the best out of modernity and reshaped it within a native mould.

- Pix credit: Lasantha Kumara, MMCA&Gagosian Quarterly

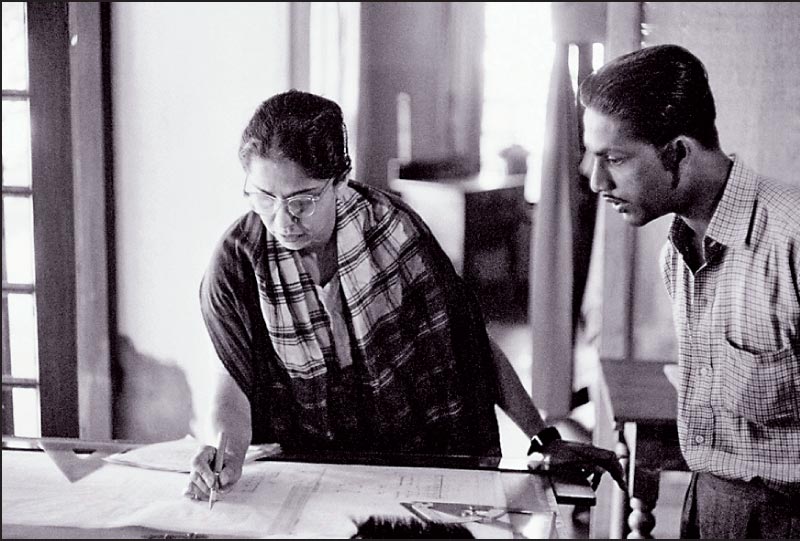

Minnette at work in 1956 (courtesy Gagosian Quarterly)

From left: Sumudu Athukorala, Irushi Tennekoon, and Sumedha Kelegama

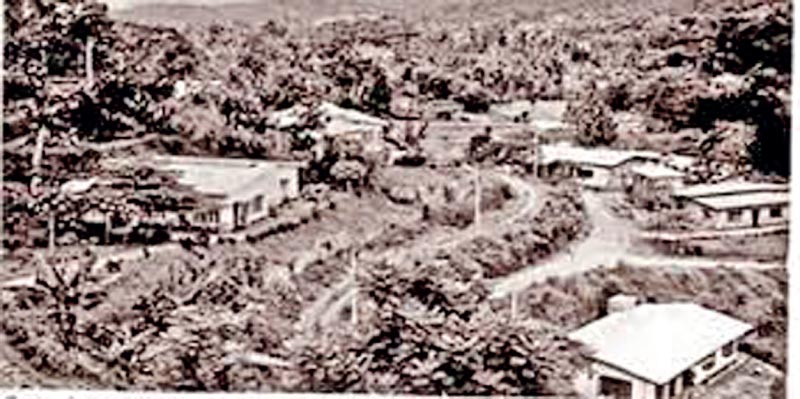

Watapuluwa Scheme under construction

One of the houses of the Watapuluwa Scheme as it stands today