Thursday Feb 26, 2026

Thursday Feb 26, 2026

Thursday, 5 June 2025 03:44 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

A Special Prosecutor’s Office against whom?

No IPKF commander or reputed Indian reporter ever claimed in retrospect that had the IPKF stayed on, Prabhakaran and the Tigers would have been beaten. The truth was the contrary. Only the Sri Lankan military was motivated enough to defeat the Tigers.

As Anita Pratap recounts Prabhakaran felt proud that he had fought off the regional superpower. The Economist (London) called Sri Lanka in 1989 “the bloodiest place on earth outside of El Salvador”. Our most distinguished historian Prof KM de Silva wrote that state power in Colombo was hanging by a thread in 1989. Had the IPKF remained, the Tigers wouldn’t have lost, but the JVP would have won and a totalitarian state established.

The very year President Premadasa called for the removal of the IPKF, the JVP, bereft of the main plank of its platform, was socio-politically isolated and destroyed. State power, the democratic republic and the market economy were saved. (https://search.worldcat.org/cs/title/indian-intervention-in-sri-lanka-1987-1990-the-north-east-provincial-council-and-devolution-of-power/oclc/42762773)

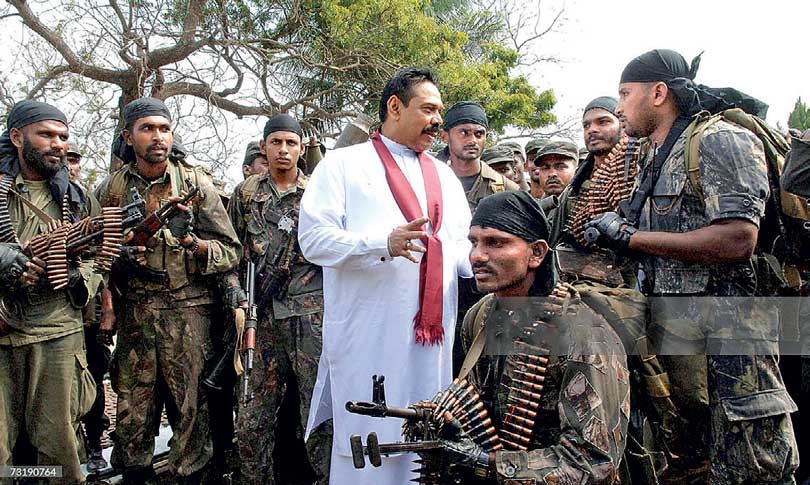

The Sri Lankan armed forces defeated the Tigers who had mauled the Gurkhas. Is the NPP Government going to submit them to a special accountability mechanism which Ranil Wickremesinghe and Mangala Samaraweera had agreed to in Geneva in 2015 in a UNHRC resolution cosponsored with the West; the same West that was moving a resolution calling for an international inquiry a week after the war ended, which we convincingly defeated in Geneva with our own pre-emptive resolution on May 26th-27th 2009?

|

Foreign Minister Vijitha Herath, Sri Lanka’s Front Line Defence

Volker Turk, UN High Commissioner for

Will NPP Govt. defend or criminalise the liberators?

Will ITAK’s Sumanthiran pick accountability over autonomy?

|

Türk and transitional justice

During UN Human Rights High Commissioner Volker Türk’s June-July visit to Colombo, a firm public commitment by the Government of Sri Lanka to an early date for the holding of Provincial Council elections under the 13th amendment, can be a viable trade-off for tricky ‘Transitional Justice’. By contrast, making contentious commitments on wartime accountability can lacerate the public consciousness and polarise the island because it touches emotive issues of the Thirty-Years War.

You don’t have to be a Sinhala ultranationalist to take exception to a Special Prosecutor’s office probing military conduct during a long war which concluded in victory, and never once posed a threat to democracy.

In most parts of the world, postwar accountability and autonomy are a zero-sum game. At a given stage, either one or the other is achievable; never both.

Barring identifiable, egregious excesses, i.e., exceptions, broad-gauge postwar accountability is almost never achievable in the context of a military serving a functioning democracy, taking orders from an elected civilian authority, and operating within the internationally recognised borders of a state. This is all the more so when there has been a clear-cut military victory rather than a hurting stalemate and negotiated peace.

Post-conflict accountability is usually achieved when dealing with a displaced or outgoing military junta, an unrepresentative, undemocratic ‘exceptional regime’ (e.g. apartheid) or in an internationally-mediated peace settlement. Hence, ‘Transitional Justice’.

In Sri Lanka, a democratically elected leader (Mahinda Rajapaksa) won a war which five democratic predecessors starting with Sirimavo Bandaranaike (Duraiyyappah was killed in 1975) failed to. So, where’s the ‘transition’, except from war to peace? Even war-to-peace wasn’t a negotiated transition; it was a dramatic victory, an event with a specific date. There was no dictatorship-to-democracy transition either.

For both the JVP-NPP administration and the Tamil parties, the accountability drive is a lose-lose game: either accountability will be resisted and prove elusive, or will cause such an opinion-shift as to damage prospects of devolution and undermine the government.

Globally, hurt patriotism, high prices and shortages produce a preponderant electoral outcome: the ultranationalist Populist Right wins.

Avoidable tragedy

The North-South fissure could have been easily bridged by timely political interventions and rational Realist reformism in policy.

While the Left valiantly battled the Sinhala racist thugs during the riots of 1958, hardly anyone raises the question of the political intervention that didn’t happen a year earlier. The LSSP and CPSL didn’t come out in support of the SWRD Bandaranaike-SJV Chelvanayakam Pact of 1957, and didn’t challenge the UNP when it marched to Kandy against the Pact.

When Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga was elected President with an unprecedented and unsurpassed 61%, all she had to do was either (a) implement devolution of power to the Provincial Councils through the 13th amendment, a cause which her late husband Vijaya Kumaratunga had fought and been martyred for, or (b) revive and implement the Bandaranaike-Chelvanayakam Pact of 1957 signed and torn up by her heartbroken father.

These were low-hanging fruit. She reached for neither. Instead, she went along with her left-liberal advisors/ideologues—some of whom are senior NPP advisors/ideologues—and wasted time and political capital on constitutional models of federalisation. These efforts empowered the Sinhala New Right.

President Dissanayake contented himself in his May 19th 2025 War Memorial speech with blaming (generic) “racism and extremism” for conflict-creation but never said anything remotely along the lines of “had the Bandaranaike-Chelvanayakam Pact, which involved no foreign force, been allowed to be implemented in 1957, there would have been no war, or any war could have been easily ended.” Any authentic leftist would have.

The problem is political

President Dissanayake and his successors in 2029 must grapple with the following:

(i)The sphere which should be the target of policy, i.e., ‘What Needs To Be Done?’.

(ii)The limits of the achievable, i.e., ‘What Can be Done, in the Present Conditions?’.

Since 1948, no Government has got both questions right at the same time, let alone the answers to both questions right. Some governments (Sirimavo, Gotabaya) have not even known the existence of the questions or have dismissed them as illegitimate. Other Governments have been in the ball-park on one question, but ignored the other. Still others have gone way overboard (e.g. CBK, Ranil’s UNP) on one or the other answer.

What was necessary throughout was Realism. We have yet to arrive at a Realist solution to the problem of reconciliation. The AKD administration may say that there is no problem of North-South reconciliation because its red flag flies across the land. This means they haven’t got the message of the recrudescence of the ITAK and other Tamil nationalist parties at the recent election, can’t get it, or refuse to get it.

President Dissanayake and the JVP-NPP can’t overcome a ‘genetic’ disability that has afflicted the JVP since birth in 1965, except for a brief interlude when the Tamil Nationalities Question was handled by Lionel Bopage. Wijeweera massively overcorrected the Bopage line, dismembering and burying it deep. It is not that the JVP-NPP should or could go back to it, but it should dig itself out of the conceptual chasm that Wijeweera lowered it into twice, in 1965 and 20 years later.

The AKD-JVP-NPP administration has not understood the location of the problem. It is situated in the domain of politics. To the extent that the JVP-NPP recognises even fleetingly the political character of the question, its answer has been simplistic: the Tamil people must politically support us and the politics of the problem automatically resolves itself. The JVP-NPP outlook combines superficial comprehension with deep delusion.

Why is the Tamil Question primarily a political question? What is its core political content? The root is the demographic formation of an island containing a constitutive contradiction of three uneven yet combined geopolitical realities:

(A)An overwhelming majority belong to one ethnolinguistic community.

(B)An ethnic minority forms a majority in a geographically identifiable, roughly contiguous area.

(C)That area lies adjacent to an ethnic kin-state (Tamilnadu) in the proximately neighbouring Indian subcontinent (unlike French-speaking Quebec separated by the Atlantic ocean from France).

These different demographic realities generate different political dynamics which require management within a single political structure, a single sovereign state, embracing the island’s natural borders.

Here are 10 points to ponder:

1.The overwhelming Sinhala preponderance means that the composition of Parliament and an executive elected directly and island-wide, will always ensure that whosoever wins the vote of the majority of Sinhalese has a built-in probability (not absolute certitude) of wielding political power at the centre.

2.If the system is a unitary state without devolution of power to a regional or provincial unit, this means Sinhala-dominant political power also over the areas in which Tamils are either an ethnic majority or Tamil is the language spoken by the majority.

3.If, however, the system is one of a unitary state with devolution of power to a provincial sub-unit, then there is a balance, if not a perfectly satisfactory solution.

4.Sinhala nationalists think the overall reality of the island is the only one that should register politically.

5.Tamil nationalists think that their regional reality is the equal of the overall reality and should yield nothing less than a federal model. They are both wrong.

6.Sinhala nationalists are right when they think the whole is greater than the part, but wrong when they think the whole can exist without political acknowledgement of the parts and their dynamics. The B-C Pact (1957) sought this outcome and its abortion caused the 30-Years War.

7.The Tamil nationalists are wrong when they think the part can be of equal importance as the whole and that the partial reality cannot be reflected within a unitary state, only a federal one.

8.Tamil ultranationalists think that the only way to solve the problem is to convert the part into the whole, through secession/independence or pan-Tamil unity with Tamil Nadu.

9.The Kurds recently found that a maximalist project eventually leads to something well below federalism and removes the autonomy they enjoyed earlier.

10.Velupillai Prabhakaran learned the hardest possible way that the part cannot sustainably exist separately, let alone sustainably assert itself against the whole.

The Anura administration’s unilateralism must be replaced by a dialogic mode aimed at consensus. This doesn’t mean getting back into the old Constitutional quagmire. Instead, it requires a transparent, structured negotiation, initially between the AKD administration and the ITAK-led Tamil bloc, and subsequently involving all Opposition parties in parliament, on this concrete agenda:

(i)The democratic reactivation of the existing system of Provincial Councils, i.e. the 13th amendment, through elections within a compressed time-frame.

(ii)Removal of dysfunctionalities within the 13th amendment by revisions which can be passed by all-parties consensus in parliament or at least by the Government’s supermajority without recourse to a Referendum.

(iii)The elimination of any discriminatory laws or regulations through an all-parties consensus, or bi-partisan consensus with the main Opposition, or through the 2/3rds majority.

The absence of functioning, elected Provincial Councils has shut down the semi-autonomous political space that the Tamil people had secured. In their effort to go beyond that space from the outset (1987), the Tamil political leadership has been the unwitting partner of the Sinhala hardliners who wanted the space shut. The revived ITAK must decide whether it wants to continue to play the game of the Sinhala hawks.

Pathetically poor political science

Unlike the NPP’s academic advisors, some whom were Chandrika Kumaratunga’s and the Yahapalanaya administration’s too, I shall not waste time – they wasted decades--on a federal/non-unitary formula, because as a political scientist I recognise the importance of ethos. This island has demonstrated its existential commitment to a unitary ethos.

Since 1949 (or 1951) the struggle for federalism or federalisation has been fought during successive administrations, and always lost. Sri Lanka is one of the many places which is allergic to federalism (e.g., Philippines) but not necessarily to provincial/regional autonomy. If the term ‘unitary’ is deleted by some sleight of hand as in the Yahapalanaya constitutional draft, there will be considerable unrest. If a federal or non-unitary package is put to the people at a Referendum, it will lose massively.

A scientific solution requires retrieving what still (barely) remains in the crucible after decades of war/s, North-South, South-South, and North-North. That’s the 13th amendment and the system of Provincial devolution. The 13th amendment is not necessarily the ceiling but is necessarily the start line. It is possible to build upon, but not go beyond the 13th amendment in this generation and historical period.

The alternative is to leave a political vacuum. The Tamil people will not be represented as a majority in the Northern Province, nor the Tamil-speaking people in the Eastern province, nor yet the Muslim people as stakeholders in the Eastern province. They will only be represented at the local government level; in sum, at the micro-level and the macro-level (the national Parliament) but not the ‘meso’ or middle-level, the province.

If the AKD administration keeps the current freeze going, it will mean the de facto abolition of a whole tier of the political system, the sub-system of provincial Parliaments.

Given the prolonged shutdown of the Provincial Councils, Sri Lanka’s political system is now like a four-legged chair standing on three legs. To change metaphors, in an ongoing economic crisis, the Provincial Councils must play their role as decompression chambers or else there will be an explosion.

The JVP-NPP’s academic activists and advisors advocate the abolition of the directly elected executive Presidency, despite the fact that had SWRD Bandaranaike been elected president, the B-C Pact would have gone through, and had Israel had an American system instead of a Parliamentary one, Netanyahu could not have been the country’s leader for almost a quarter century, in an axis with small but growing parties of fascists.

NPP academics, be they ideologues or emeritus advisors, profess to subscribe to the concept of ‘Polity’ but pursue a contrary policy. ‘Polity’ features in Aristotle’s typology as a preferred form of state which he regards almost as an ideal. This is because it avoids the degeneration of the principal types of state, monarchy and democracy, into their extremes/opposites, tyranny and anarchy, precisely by being a mixed type of Constitution with features of both.

The American (including Latin American) and French presidential systems are the closest we come to such a mixed type of Constitution. Among the ancient sources of inspiration of America’s Founding Fathers were a mixed system as advocated by Aristotle (Plato’s Republic was also a synthesis) and the model of the Roman Republic.

The Gaullist presidency as adapted by JR Jayewardene is also democratic republic with a mixed system: the directly-elected Presidency and a strong Parliament from which the Cabinet is drawn (unlike in the US model).

What we have on this island is basically a ‘Polity’, or closer to one than any system we have had since 1948, though it is in need of rectification and fine-tuning. The abolition of the executive Presidency and return to a Parliamentary system would be an unmixed system, the very opposite of an Aristotelian ‘Polity’.

Yet, Sri Lankan academic and intellectual fellow-travellers of the JVP-NPP supposedly subscribe to the concept of a Polity while advocating its dismantling and substitution by the exact opposite—risking everything Aristotle warned against.

Moreover, they fail to comprehend that the directly-elected executive Presidency makes the majority less insecure about possible centrifugal behaviour of Provincial Councils. No nationally-elected Presidency as apex, no Provincial Councils.

(The writer was an elected Vice-President of the UN Human Rights Council 2007-2008.)