Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Wednesday, 20 April 2016 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Beginning this decade, Sri Lanka will experience a decreasing youth population and the dividend potential will decrease accordingly. The window is expected close in around 2037. A comprehensive human capital strategy for youth is needed if Sri Lanka to reap the full benefits of this narrow window of opportunity

Beginning this decade, Sri Lanka will experience a decreasing youth population and the dividend potential will decrease accordingly. The window is expected close in around 2037. A comprehensive human capital strategy for youth is needed if Sri Lanka to reap the full benefits of this narrow window of opportunity

During Avurudu, the cities are emptied as people head ‘home’ to the outstations. Some of us city folks who visit relatives in those areas get to see our youth relaxed and happy in their natural habitat as they take the lead in Avurudu uthasavas, cross-village runs and other Avurudu activities. How many of them are home for the holidays from work or study in the city? How many never left and have been just hanging out?

The much-quoted story of ‘140,000 or so youth qualify at GCE (A/L) but only 22,000 gain entrance to universities’ does not give a true picture of our youth, because the numbers do not refer to a cohort of the same age. In fact, these numbers grossly exaggerate the pass rates because those sitting for the A/L often use all three attempts allowed and 50% or more never sit for the examination.

National surveys conducted by Sri Lanka Department of Census and Statistics give a better picture of our youth population. By international convention, the youth population in a country is defined as those in the 15-29 age group. The 2011 Census of the population estimates this youth population to be at 4.5 million.

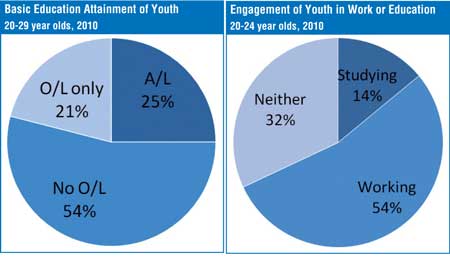

A 2014 report from the Ministry of skills Development titled ‘Youth and Development’ brings together data from the population Census and the 2009/2010 Higher Education Income and Expenditure Survey (HIES) to give a more complete picture of the 20-24 age group of youth in Sri Lanka. For the purposes of this column, the author added and the data from Quarterly Labour force Survey (QLFS) from the third quarter of 2010 to further complete the picture.

Of the 1.5 million youth in the 20-24 age bracket, 3% are in ‘Universities’, 4% in ‘Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET)’ and another 7% in ‘Other’ institutions for total of 14% saying they study at some institution. This leave an 86% of the population as not attending an education or training institution (Youth & Development, 2014). The labour force participation data for 2010 the quarter tells us that 54% of this age group participated in the labour force, leaving 32% as not attending or not working.

Youth and the demographic dividend

A demographic dividend occurs when the labour force temporarily grows more rapidly than the population dependent on it, freeing up resources for investment in economic development and family welfare (Lee & Mason, IMF, 2016). In Sri Lanka, this period apparently started around 1991 and is expected to last till 2037. In 2011, we recorded highest number of the working-age populating from 15 - 59 population 4.7 million.

The quality of life for the older generation depends on the quality of employment of the working age population, particularly if the older generation has not saved enough for retirement. The youth in the 15-24 age bracket represents a critical component of the labour force. Policymakers still have room for improvement with this component of the population. The status of the 20-24 year old sub set is particularly informative of the quality of employment of the future workforce because that is the prime age group for education and training beyond school.

Youth and their basic education levels

Basic education attainment of youth gives an indication of the preparedness of youth for further education and training. The picture does not look good, because 54% of the youth population have left school without acquiring pass in the GCE (O/L) examination. Of the rest, 25% of this cohort will have passed the A/L examination, 21% will have a passed O/L (Youth Development Report, 2014).

Let us look the youth in each work or study category in relation to their basic education attainment and government expenditure in each category.

Those who work (54%)

As noted in the Youth & Development Report, youth from low income families have no choice but to engage in low-paying job after leaving school, pushing them into a vicious cycle of poverty. Waiting for a secure job in the government sector is not an option for these youth because such a wait-period is a burden on their families. As a result, these youth gravitate to low paying jobs and would remain there unless their employers move up the value chain in the products of services they offer. Government’s support for small and medium enterprises and training for their workers is critical in this regard.

Those who study (14%)

Three percent of those engaged in studying at an institution attend a university. This 3% attending public universities should be the ones to take the lead in creating jobs for the other 97%, but, unfortunately, they are the first to go out with a begging bowl to the government.

Except for the Kotelawala Defence University and the Ocean University, only the 15 institutions under purview of the University Grants Commission (UGC) currently bear the name university. The highest per student expenditure is incurred for the UGC universities. For example, the Government allocated 9.8 billion for higher education at roughly Rs. 140,000 per student in 2016 Budget. Universities argue for increased funding, but funding should not be increased without appropriate performance measures in place.

Another 4% of the 20-24 age cohort attend TVET institutions spread across the country. A small number of these TVET institutions are successful non-profit initiatives catering to low income youth. Rs. 3 billion was allocated for the TVET sector leading to a per student expenditure of around Rs. 60,000, in the 2016 Budget. Given the quality issues in these TVET public sector institutions, public-private partnerships with some of the successful private initiatives should be considered for this sector.

The most interesting group of youth is the 7% who study at ‘Other’ institutions. Most these institutions likely to be established as for-profit institutions. Radical university students and faculty members seem to think that these private initiatives should be banned and these students should be absorbed into the public university system. A more astute measure would be to maintain the public universities at their present size and restructure them to perform at world class level, and support students already attending private institutions or engaged in work, through an education voucher system.

Those who do neither (32%)

About 32% of the 20-24 age cohort have identified themselves as neither working nor attending an institution for education or training. We don’t have details on this group, but one guess would be that this group comprise of those with O/L or A/L certificates and most of them are awaiting a secure government job. Given difficulties in travel and issues accommodation outside of the home, most of this 32% may consist of young women who are doing unpaid work at home and/or following an odd ‘class’ or two.

A human capital strategy to reap the demographic dividend

Beginning this decade, Sri Lanka will experience a decreasing youth population and the dividend potential will decrease accordingly. The window is expected close in around 2037. A comprehensive human capital strategy for youth is needed if Sri Lanka to reap the full benefits of this narrow window of opportunity. If the present day university students truly care about equity in education, they should be clamouring for better performance by our school system and better quality university education that prepares the 3% of them to take the lead in job creation for the other 97%.

Currently, our school system fails to secure an O/L certificate to 54% of our youth. The rates are increasing, but not sufficiently. On the other hand public university personnel behave as if a competitive written exam as entry criteria absolves them of accountability for quality and relevance in the education imparted.

The best human capital strategy for Sri Lanka is not to lose sight of the forest of ‘1.5 million youth in the 20-24 age group’ for the ‘vocal and visible 3% segment of a youth population in the universities,’ but to develop policies to guide each category depending on their basic educational achievement, aptitudes and potential for helping Sri Lanka get out of the middle-income gap.

Budget allocations should be targeted with specific objectives for each group. University administrators and faculty members should be made aware that their responsibility is to educate their students to create jobs, not expect jobs. Performance measures should be designed accordingly. Members of the faculty who like to think that they teach their students to think should have no reason to worry.

As I pointed out in a recent column on Arts and Humanities education (http://www.ft.lk/article/528438/Arts-and-Humanities-education-deserves-a-second-look), the software industry, for example, is increasingly discovering the value of sharp minds with an Arts and Humanities education.

TVET programs should be judged by the feedback from industries for which their graduates are targeted and performance measures for the sector set accordingly.

The National Youth Services Council (NYSC) is best equipped to serve those who neither work nor study. In fact, the percent of youth claiming to be in this group can be reduced by taking every young person turning 15 under the NYSC’s wings for counselling and orientation for further study. An education and training ID card with facility for crediting and debiting money should be considered. The UNP manifesto proposed such for university students. A national student card issued to all youth completing 15 would send the message that they all have the potential to join a skilled and knowledgeable workforce at different levels with different emphasis.