Friday Feb 27, 2026

Friday Feb 27, 2026

Tuesday, 19 July 2016 00:06 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

July 15 marked 36 years since the great general strike of 1980 when 40,356 public and private sector employees lost their jobs for the first time in the history of Sri Lanka.

The United National Party which contested the general election of 22 July 1977 under the slogan ‘Let’s Create a Righteous Society’ won 140 out of 168 Parliamentary seats. It was a landslide victory which reduced the number of SLFP seats to seven; later increased to eight when independent MP for Harispattuwa Wijesiri joined the party. The Tamil United Liberation Front which promised a Tamil Eelam state succeeded in winning 18 seats.

On 4 October 1977, Prime Minister J.R. Jayewardene got Parliamentary approval for the Second Amendment to the Constitution by a two-thirds majority.

Unable to bear rising prices during this time the working class demanded a monthly wage increase of Rs. 300 (Rs. 10 per day) and an allowance of Rs. 5 every rising cost-of-living index. Although the Government decided to reduce the number of public holidays, trade union opposition led the rulers to rescind it. Using majority Parliamentary power, the Government resorted to suppressing Opposition political parties and trade unions.

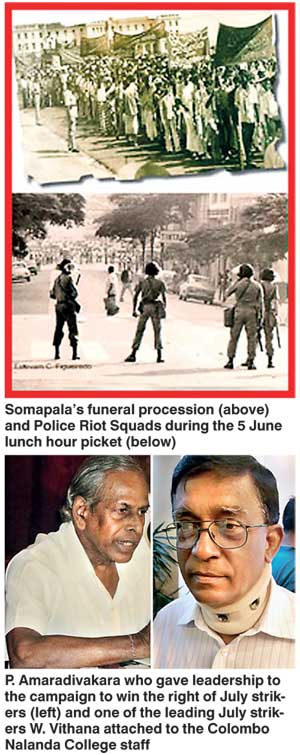

Commemorative rally for winning the demands of the July strikers

Commemorative rally for winning the demands of the July strikers

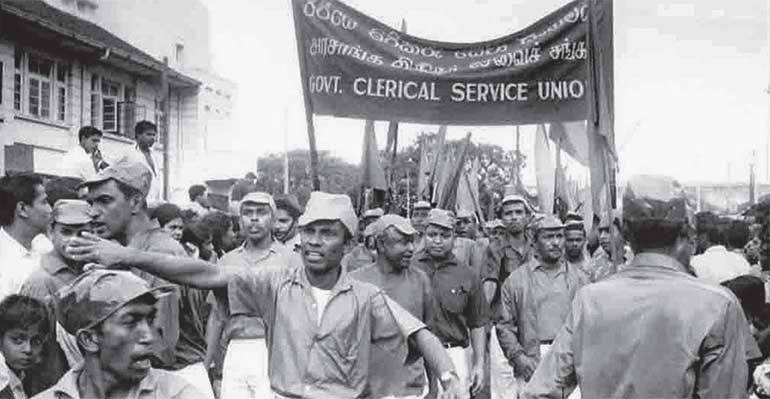

In order to deal with this situation, the Trade Unions Working Committee held a national congress with the participation of 1,024 trade unionists representing all spheres at the Sugathadasa Stadium, Colombo on 8 and 9 March 1980. There it was decided that a national protest campaign should be launched during the lunch hour on 5 June 1980 to win their demands including the monthly wage increase of Rs. 300.

In response to this the UNP trade union, Jaathika Sevaka Sangamaya and the unions affiliated to the pro-UNP Government Services National Trade Union Federation declared 5 June 1980 a day of solidarity with the Government.

On the same day, nearly 400,000 State and private sector employees staged pickets, demonstrations, protests and meetings opposite their workplaces. There was widespread support for this and the protesters were in a militant mood. At the same time pro-Government trade unions staged meetings to support the ruling party.

Two armed gangs which emerged from the direction of the Government Supplies Department at Chittampalam Gardiner Mawatha and Lake House started attacking the protesters with stones. They also threw a bomb killing a trade union member D. Somapala, who was a Supplies Department Employee.

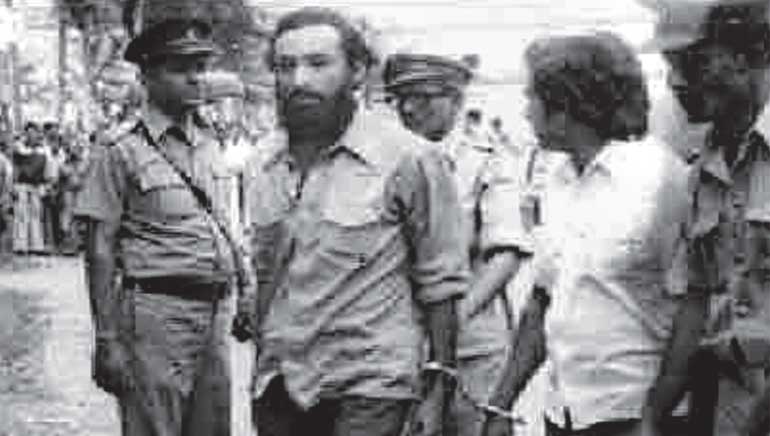

Vasudeva Nanayakkara being taken to be remanded after being taken into custody during a July strikers’ demonstration on 8 August 1980

Vasudeva Nanayakkara being taken to be remanded after being taken into custody during a July strikers’ demonstration on 8 August 1980

Assistant Superintendent of Police, Colombo Fort area, N.I. Ratnayake, in his report on the incident submitted to IGP Ana Seneviratne, stated: “There were over 100 demonstrators opposite the Government Supplies Department on 5 June at 12:45 p.m. At this time a group in jeep No. 31 Sri 1111 which came from the direction of Slave Island started throwing sticks and stones at those who were picketing. Then there was a sound of an explosion. Six injured persons were hospitalised. Agalawatte MP Merril Kariyawasam was seen seated on the front seat of the jeep which moved away from the scene before going past Lake House. One person died in the incident.”

Nine years later, in September 1989, during the second JVP insurgency, the Deshapremi Janatha Vyaparaya (Patriotic People’s  Movement) assassinated Merril Kariyawasam as “punishment” for causing Somapala’s death, according to DJV’s radio channel ‘Ranahanda’ (militant voice).

Movement) assassinated Merril Kariyawasam as “punishment” for causing Somapala’s death, according to DJV’s radio channel ‘Ranahanda’ (militant voice).

Somapala’s death shocked the working class. He was the 13th to be killed in such a manner after the deaths of plantation worker Govindan during the Muloya strike on 19 January 1940 and Velupillali Kandasamy, Government Clerical Services Union (GCSU) member killed during a strike on 5 June 1947. The other 11 died during the hartal of 1953.

Somapala, a father of two, who resided at Narahenpita, died as a result of injuries to the heart, lungs and ribs, according to the report of Judicial Medical Officer B.M. Kariyawasam and Professor H.J. Fernando. The Coroner decided to hold a magisterial inquiry into Somapala’s death at the request of Bala Tampoe, Mangala Munasinghe and Peter Jayasekera on behalf of the victim’s family, ignoring the protests of ASP C.P. Jayasuriya.

Since Somapala’s house was too small, the body was kept in a neighbouring house. Later it was taken to the Public Service Employees Trade Union headquarters in Fort. The funeral was organised by the United Trade Union Working Committee.

Thousands of employees obtained half-day’s leave to pay their last respects to this ordinary worker. Over 50,000 mourners attended his funeral at the General Cemetery, Borella. The writer remembers seeing nearly 100,000 people gathered on either side of the road to watch the funeral procession. (In later years over 100,000 attended the funeral of Thrimavithana and around 50,000 came for Lalith Athulathmudali’s funeral)

An open verdict was delivered after the magisterial inquiry held into Somapala’s death from 8 June to 28 August 1980. According to the verdict, he was killed as a result of severe injuries caused by the violent actions of a rival group which came in an illegal procession

Following incidents that occurred during his funeral, 12 employees of the Ratmalana Railway Workshop were interdicted on 12 June 1980. Other workshop employees struck work on 7 July 1980 demanding that the interdicted workers be reinstated. The strikers were supported by employees of No. 18, 19, 26, 36 and 38 workshops. They joined the strike on the morning of 8 July 1980. A total of nearly 8,000 had stopped work by 9 July, bringing the entire train services to a halt.

The United Trade Union Working Committee met on 11 July 1980 and demanded that a Rs. 300 monthly wage increase be given immediately to public and private sector employees and they be also given an allowance of Rs. 5 every rising cost-of-living index and that the interdicted workers be reinstated unconditionally.

The Working Committee also warned that it would launch a country-wide general strike if there was no response from the Government to these demands by 14 July 1980. By this time 24,810 railway employees throughout the island had joined the strike. Health sector employees joined the strike on 15 July.

The UNP rulers announced that if a general strike was launched, the Government would consider the strikers as having vacated posts. The Cabinet met on 16 July and on the same night declared an island-wide State of Emergency. Accordingly, railway, CTB, postal, hospital, educational, fuel distribution and port services were declared essential services under Emergency Regulations, thereby making the strike illegal.

State Ministry Secretary Dr. Sarath Amunugama was appointed Competent Authority and a news censorship was imposed with  effect from 18 July. Opposition newspapers Eththa, Srilaka and Janadina came totally under this censorship and the State-controlled media reported only what was favourable to the Government. Reporting of MPs’ statements on the strike made during Parliamentary debates came under the control of the Parliament’s News Censorship Committee.

effect from 18 July. Opposition newspapers Eththa, Srilaka and Janadina came totally under this censorship and the State-controlled media reported only what was favourable to the Government. Reporting of MPs’ statements on the strike made during Parliamentary debates came under the control of the Parliament’s News Censorship Committee.

Ignoring the Government’s announcements, health sector employees on 15 July, Government Department and Local Government employees on 17 July and school teachers on 20 July joined the great general strike.

Although the JVP did not officially participate in the strike, it requested persons still working to join the strike. After the Lanka Guru Sangamaya (Teachers Union) of which the General Secretary was Rohana Wijeweera’s brother-in-law H.N. Fernando, joined the strike, the Guru Sangamaya split. Bala Tampoe’s CMU (Ceylon Mercantile Union) did not join the strike. Earlier too, the CMU avoided participating the banks’ strike which took place during the previous United Front Government.

However, nearly 100,000 employees joined the general strike of July 1980, thus crippling the Government’s administrative functions and daily services. The UNP Government held meetings presided over by President J.R. Jayewardene at Maliban Junction, Ratnapura on 19 July 1980 and opposite Tower Hall, Maradana on 21 July against the general strike. It was at this Maradana meeting the President said that under the prevailing law he had the power to do anything except making a woman a man.

The Government suspended the payment of July salaries to the strikers. All trade union offices in State-owned buildings were closed and sealed. The strikers were given an opportunity to report for work before 23 July under certain conditions. Many were able to get their jobs back claiming that were seriously ill due to various reasons during the strike period.

Prime Minister Ranasinghe Premadasa announced on 24 July that since 40,356 employees did not report for work, the Government would consider them as having vacated posts under the regulations. Thereafter UNP MPs obtained 100 job applications per electorate from jobless persons who replaced the 40,356 strikers. Accordingly 8,421 persons registered with the Job Bank were recruited to Government Departments and State Corporations by 22 July 1980. By August all vacancies had been filled on the recommendations of UNP Parliamentarians.

On the morning of 8 August 1980, a demonstration with the participation of thousands was held opposite the Fort Railway Station, demanding that the strikers being given their jobs back. Disregarding the Emergency Regulations, the demonstrators began marching towards the President’s House. Near the General Post Office, Police baton charged the marchers and dispersed the crowd.

Strikers who lost their jobs at a demonstration demanding relie

Strikers who lost their jobs at a demonstration demanding relie

Trade Union Leaders Alavi Maulana, Vasudeva Nanayakkara, Gunasena Mahanama, D.I.G. Dharmasekera and Dr. Vikramabahu Karunaratne were arrested and remanded. By 15 August 1980, the State of Emergency was lifted since the UNP Government had succeeded in totally suppressing the July general strike. News censorship too was lifted.

The July general strike caused 40,356 persons to lose their jobs, causing over 300,000 of their dependants to end up in utter misery. Some strikers who had lost their jobs committed suicide, being unable to maintain their families. Family lives were disrupted. Some became mental patients. Children were orphaned. The jobless strikers were forced to vacate the houses where they were living on rent.

Hundreds of them became beggars. In 2013, a national newspaper carried the story and photo of a striker begging in Borella. A few managed to survive by their own effort and with the help of relatives. Others became pavement hawkers, drivers and bus conductors.

In later years, those who campaigned on the July strikers’ behalf were not the trade unions that called for the strike but the July Strikers Combined Organisation headed by P. Amaradivakara assisted by Sri Lanka Mahajana Party President, the late Ossie Abeygunasekera. MP Vasudeva Nanayakkara has been continuing to appear on behalf of the July strikers to this day, according to the organisation.

As a result of their efforts, all July strikers who were employees in Government and Local Government Services were given pension rights with bonuses in 1989. Steps were also taken to provide each of them with a monthly allowance of Rs. 5,000 for the rest of their lives. The July 1980 General Strike can be considered a decisive moment in the history of Sri Lanka’s Working Class. The biggest lesson it taught them was the importance of building trade union organisations independent of political parties.

(The writer is a senior journalist who can be reached at [email protected].)