Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Tuesday, 28 November 2023 00:05 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The CBA should be modified to permit the CBSL to purchase Government debt in a manner consistent with its overall interest rate strategy, and not simply as a short-term ‘transitory provision’ at the discretion of the Governor of the CBSL

|

In Part I, we examined the rationale and implications of the CBSL’s prohibition from purchasing Government securities under the new CBA. We argued that this rationale is fundamentally flawed and likely to have detrimental effects on the Sri Lankan economy, especially growth and employment. In Part II we delve into the rationale and implications of the CBA making the primary objective of the CBSL the control of inflation (and stability of the financial system) and increasing its independence in the pursuit of this objective.

In Part I, we examined the rationale and implications of the CBSL’s prohibition from purchasing Government securities under the new CBA. We argued that this rationale is fundamentally flawed and likely to have detrimental effects on the Sri Lankan economy, especially growth and employment. In Part II we delve into the rationale and implications of the CBA making the primary objective of the CBSL the control of inflation (and stability of the financial system) and increasing its independence in the pursuit of this objective.

Building on the arguments developed in Part I, we contend that this reasoning is also fundamentally flawed and likely to exacerbate the negative impacts on economic growth and employment in the Sri Lankan economy resulting from the CBSL’s prohibition from purchasing Government securities.

In its 2023 report on the state of the economy, the CBSL claims that the new CBA would allow it to be more independent, thereby strengthening policies aimed at managing inflation and inflation expectations (CBSL 2023, p.32). Wijewardena (2023) notes that the US Senate Committee on Foreign Relations indicated that making the CBSL independent was a necessary precondition for approving the Extended Fund Facility (EFF) package. While refraining from commenting on the ability of the US Senate Committee to influence the IMF’s decision regarding the approval of an EFF with the Government of Sri Lanka, or even the audacious nature of its insistence on making another country’s central bank ‘independent’, Wijewardena (2023) argues that the CBSL should nevertheless be made independent because it is for the ‘good of citizens of Sri Lanka’.

The intellectual origins of demands for the independence of central banks and their primary focus on controlling inflation, like the intellectual origins of the prohibition of central banks from purchasing Government debt, can be traced back to the modern Quantity Theory of Money (QTM). Proponents of the QTM argue that there is a dichotomy between real phenomena, such as growth and employment, and monetary phenomena, such as inflation and the trade balance, as well as between the policy measures deemed relevant to influencing these phenomena. They see factors having a bearing on monetary phenomena have no bearing on real phenomena, and vice versa. Hence, they deny that monetary policies targeting the quantity of money in the system in order to control inflation and the external balance have a bearing on growth and employment, except possibly over the short-run as a result of erroneous inflationary expectations. It is this premise of a dichotomy between monetary and real phenomena that is used to justify the independence of a central bank and its exclusive focus on the control of inflation.

Once it is accepted that central banks implement monetary policy by setting interest rates with a view to influencing aggregate demand and that the latter has a bearing on both monetary and real phenomena, this dichotomy argument falls apart. It can no longer be argued that central banks can focus their attention solely on inflation and ignore the impact their policies have on other macroeconomic phenomena such as economic growth and employment. Moreover, since fiscal policy also has a bearing on aggregate demand, and via this both monetary and real phenomena, it cannot be argued that monetary policy can be implemented by the central bank without reference to fiscal policy and, perhaps more fundamentally, without reference to the priorities accorded by the Government to targeting these phenomena.

Furthermore, once it is recognised that monetary policy is relatively ineffective in supporting aggregate demand in certain circumstances, such as a recessionary environment, it cannot be argued that it alone can, or should, be relied on to attain the desired macroeconomic goals.

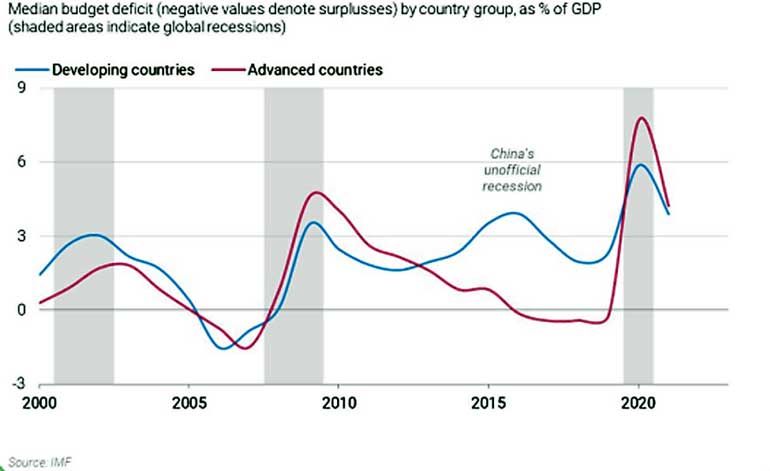

Figure 1 shows the budget deficits for advanced and developing countries over the period 2000-2021. It illustrates that the tendency of all countries, including developing countries like Sri Lanka, is to run expanded budget deficits in recessionary environments – these being the shaded areas in the chart – with these deficits funded in large part by central bank purchases of Government debt. This is in spite of the fact that budget deficits could aggravate inflationary pressures in developing countries at these junctures.

Turning now to Sri Lanka, it should be apparent that the CBA, like its predecessor – the Monetary Law Act (MLA) – is underpinned by the erroneous premise that there is a dichotomy between monetary and real phenomena as well as the policies intended to influence these phenomena. One consequence of this premise is that it provides the CBA, like the MLA, with a justification for limiting the objectives of monetary policy to the control of inflation (and stability of the financial system). As noted in Part I, this is in spite of the fact that it is accepted the CBSL, like most other central banks in the world, implements monetary policy by setting interest rates with a view to influencing aggregate demand, and that the latter has a bearing on both monetary and real phenomena – on both inflation and economic growth (See CBSL, 2023, p.34).

This means that the CBSL should not be permitted to focus on the control of inflation without paying heed to the negative impact of its policies on phenomena such as growth and employment and, more fundamentally, the priorities accorded by the GOSL to various macroeconomic phenomena. When CBSL officials are asked to justify their policies and their consequences to Parliament they should not be allowed to absolve themselves of responsibility for the negative impact their policies have on phenomena such as growth and employment using the argument that these policies only have a bearing on monetary phenomena.

A second consequence of the dichotomy premise is that it is used to justify the increasing policy-making independence of the CBSL. However, once it is recognised that the policies of the CBSL impact on more than simply inflation there can be no justification for this independence. This is not to deny that the CBSL, like the Sri Lankan bureaucracy in general, should be free from interference from any and all quarters – not only political interference. Rather, it means that the CBSL should not be permitted to pursue policies that have a major impact on other economic (and social) phenomena without being required to take this impact into account when formulating its policies and being held accountable for their impact. Specifically, since it is recognised that the CBSL’s interest rate policies have a bearing on inflation and growth, it makes no sense to only hold the CBSL accountable for the attainment of inflation targets and not also the consequences its policies have for economic growth.

Taken together, Parts I and II suggest the need for a significant modification of the CBA. The major modifications they suggest are twofold. First, the CBA should be modified to require the CBSL to take into account the impact of its interest rates policies on a broader range of macroeconomic objectives than simply inflation, with these objectives and the priorities attached to them determined by the GOSL and, by extension, the democratic process. This follows from the recognition that changes in aggregate demand resulting from changes in interest rates do not only have a bearing on inflation, but also on other macroeconomic phenomena such as growth and employment. Second, the CBA should be modified to permit the CBSL to purchase Government debt in a manner consistent with its overall interest rate strategy, and not simply as a short-term ‘transitory provision’ at the discretion of the Governor of the CBSL. This will;

References:

CBSL (2023) The Central Bank of Sri Lanka Annual Report 2022. Colombo: Central Bank of Sri Lanka.

Wijewardena, W.A (2023) ‘New central banking bill: Positive but gaps need to be filled – Part I’ Financial Times, 7 March. https://www.ft.lk/columns/New-central-banking-bill-Positive-but-gaps-need-to-be-filled-Part-I/4-746017.

Figure 1: Medium budget deficits for advanced and developing countries as percentages of GDP, 2000-2021

(Bram Nicholas is the COO of the research and training company ETIS Lanka.)

(Howard Nicholas is a retired associate professor in economics, Institute of Social Studies (The Netherlands).)

Part I of this article can be found at https:// www.ft.lk/columns/ Why-the-Central-Bank- Act-should-be-significantly- amended-by-a-future- Sri-Lankan-government- Part-I/4-755488