Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Tuesday, 25 November 2025 00:01 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

A young woman in Kandy wakes up to find her private photos shared once in trust with her partner, circulating through WhatsApp groups she had never even heard of. In Jaffna, a university student who dared to speak up about women’s rights and equality for all, receives a series of anonymous messages threatening him. A young graduate from Colombo, just weeks into his first job, becomes a target of relentless gender trolling owing to his preferred gender identity. An activist with a disability from Batticaloa, fighting for inclusion finds herself excluded, bullied and targeted with hate speech.

These stories represent people from all walks of life, but the violence that has followed them into the digital sphere, remains the same. It is swift, merciless and for the most part, anonymous. Cyberspace, where harm spreads fast with long-term consequences, enables perpetrators to hide behind their screens and keyboards, while survivors face backlash compelling them to suffer in silence. This is the reality of Technology-Facilitated Gender-Based Violence (TFGBV).

The United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) defines TFGBV as any form of gender-based harm or violence that is perpetrated, supported, or amplified through digital tools or technology by one or more individuals. This can happen on online platforms like social media, messaging apps, or websites, or through other technological means, even if they are not connected to the internet.

There is no doubt that technology is a great tool that connects people, empowers them with learning, opening a multitude of opportunities for all. Over time, advancements in technology have contributed to equality and progress across the world, enabling people to access comprehensive knowledge and skills at their fingertips.

There is no doubt that technology is a great tool that connects people, empowers them with learning, opening a multitude of opportunities for all. Over time, advancements in technology have contributed to equality and progress across the world, enabling people to access comprehensive knowledge and skills at their fingertips.

However, for too many, including women, girls, and marginalised groups technology has exposed them to a new form of Gender-Based Violence (GBV), where stigma is weaponised against survivors more brutally than ever before. This brings me to the question, what exactly does TFGBV refer to?

A recent study by UNFPA and UN Women (2025) on TFGBV experienced by women, girls, LGBTQIA+ persons, and ethnic minorities in Sri Lanka involving communities across Colombo, Kandy, Ampara, Jaffna, and Galle, revealed that 56% of women and 62% of LGBTQI+ respondents felt unsafe online. Among the respondents, nearly one in three (29%) reported experiencing digital violence firsthand, while 12% reported experiencing TFGBV daily. A staggering 90% were of the belief that social media increases the risk of TFGBV.

What we must bear in mind is that behind each percentage is a person whose dignity was shattered in a space that should have been safe. These figures represent the national reality of digital violence unfolding in real time.

Technology-facilitated gender-based violence and adolescents

Teenagers are now online more than ever before. A decade ago, you would find children playing outside, in their own imaginary worlds. But today, the digital sphere is their playground. So much of their world is online: from friendships, playtime, and learning to even first love. What we must not forget is that these spaces are also flooded with misogyny, manipulation, misinformation, and fabricated content that distort reality and shape how young people see themselves.

Global research shows that girls encounter online harassment as early as 14, while new technologies like AI-generated deepfakes are increasingly used to target them. A study by Save the Children (2025), revealed that 40% of teenagers believe that sharing intimate images with their partners is normal. Such images often become tools of intimate partner violence, used to blackmail, extort and control girls.

The United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) defines TFGBV as any form of gender-based harm or violence that is perpetrated, supported, or amplified through digital tools or technology by one or more individuals. This can happen on online platforms like social media, messaging apps, or websites, or through other technological means, even if they are not connected to the internet

Imagine being a 14-year-old girl threatened by someone who says they will share edited intimate photos of you in school uniform online if you don’t comply with their demands. Where do you turn? Who do you trust? And what happens when the adults who should protect you respond with blame rather than support? At the moment they need us most, many girls choose isolation and silence, because of stigma and the fear of being punished, judged, or having their phones taken away.

Data shows that the percentage of girls who feel comfortable with parents or guardians knowing what they do online drop from 84% at ages 9-11 to just 34% at ages 12-14 (Save the Children, 2025). Too often, our reactions to digital violence begin with “Why did you post that?” or “Why did you take this photo?” instead of “How can I help you?” As a result, girls shrink themselves to survive harm they did not cause.

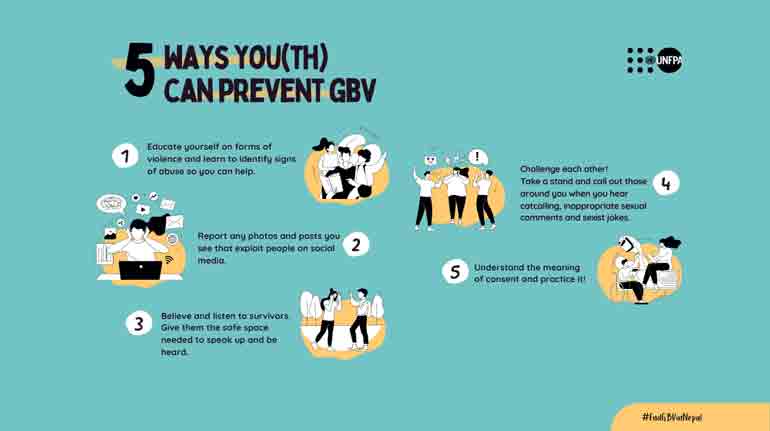

This is why we need to empower young people to protect themselves. This could be achieved by collective action across sectors including the government and parents to integrate digital literacy and online safety into school curricula; teaching consent, mutual respect, and healthy relationships; and having open, non-judgmental conversations focused on values, empathy, respect, kindness, and boundaries with adolescents and young people.

#OurDigitalSpace: End online violence for GBV-free Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka is entering a rapidly evolving digital age, with over 12.4 million internet users, more than 29 million mobile connections, and 8.2 million social media identities recorded in early 2025. As digital access expands, so should our laws, norms, and public conversations. For many women and girls, already navigating domestic violence, workplace harassment, sexual violence, and abuse in public spaces including transport, the online sphere has become another space where harm continues.

The UNFPA and UN Women study on TFGBV (2025) across Colombo, Kandy, Ampara, Jaffna, and Galle in Sri Lanka, revealed an alarming spectrum of digital violence. Over a third of respondents (36.9%) had fake profiles created in their name, and the same proportion experienced the non-consensual sharing of intimate content. Nearly one in four (25.3%) reported being affected by deepfakes. Another 24.3% faced the unauthorised exposure of personal information as well as gender trolling. These forms of abuse show how deeply digital violence is reshaping the daily lives and safety of women, girls, and young people in Sri Lanka.

Survivors are faced with stigma, reputational fears, and victim-blaming that discourage them from seeking help. Gaps in legal protections and institutional capacity further limit people’s access to justice. In today’s world where the boundary between online and offline has almost disappeared, digital violence is no longer just a women’s issue. It is a national development priority.

A recent study by UNFPA and UN Women (2025) on TFGBV experienced by women, girls, LGBTQIA+ persons, and ethnic minorities in Sri Lanka involving communities across Colombo, Kandy, Ampara, Jaffna, and Galle, revealed that 56% of women and 62% of LGBTQI+ respondents felt unsafe online. Among the respondents, nearly one in three (29%) reported experiencing digital violence firsthand, while 12% reported experiencing TFGBV daily. A staggering 90% were of the belief that social media increases the risk of TFGBV

Addressing TFGBV is integral to Sri Lanka’s commitments under the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), the National Action Plan II on Sexual and Gender-Based Violence (SGBV), and Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment Policy to realise Sustainable Development Goal 5 on Gender Equality.

While Sri Lanka possesses foundational legislation, such as Section 345 of the Penal Code, which criminalises sexual harassment, there is a critical requirement to strengthen these laws to explicitly cover TFGBV. This legislative reinforcement is essential and urgent, given the country’s contemporary digital landscape and the increasing prevalence of associated online risks.

Sri Lanka also has a growing community of people who refuse to look away. Survivors rebuilding their lives, parents choosing to listen, teachers guiding with care, men and boys stepping up, and leaders willing to act.

Among them, Sri Lanka’s women in leadership across sectors, as well as the Women Parliamentarian’s Caucus have played a vital role in pushing digital safety, survivor protection, and online accountability into national policy discussions.

At UNFPA, we are committed to engaging with the government, civil society, private sector, and tech companies to strengthen the prevention, protection and response mechanisms, as well as to implement comprehensive legal provisions to address TFGBV. We also recognise the vital role of parents, caregivers, and teachers as essential partners in this effort. By creating safe and trusting environments, where young people feel heard and supported, they form the first and most important line of protection against online violence.

Survivors are faced with stigma, reputational fears, and victim-blaming that discourage them from seeking help. Gaps in legal protections and institutional capacity further limit people’s access to justice. In today’s world where the boundary between online and offline has almost disappeared, digital violence is no longer just a women’s issue. It is a national development priority

A whole-of-society approach is essential to address this new form of violence. This ranges from having honest, open conversations in our homes, to introducing clearer legal definitions for digital abuse, enabling survivor-centred reporting pathways, implementing faster content-takedown procedures, and strengthening institutional capacities to respond effectively to online violence. Together, we can ensure that every person, including women and girls, can navigate digital spaces safely for an inclusive Sri Lanka.

This year’s 16 days of activism against gender-based violence calls on us to reclaim #OurDigitalSpace, a space that belongs not to perpetrators, but to changemakers from all walks of life seeking connections, opportunities, and resilience. A space where young girls deserve to grow without fear; where men and women alike pursue their aspirations; a space that reflects an inclusive and GBV free Sri Lanka, leaving no one behind.

(The author is Officer-in-Charge, UNFPA Sri Lanka).