Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Wednesday, 11 February 2026 00:20 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Colombo is currently witnessing a striking convergence of religion, diplomacy, and politics at the Gangaramaya Temple, where the sacred Devnimori Buddha Relics are on public display. Excavated in Gujarat and brought to Sri Lanka with full state honours, the relics are being exhibited for public veneration. President Anura Kumara Dissanayake inaugurated the exposition, underscoring its national and symbolic significance. Framed as a celebration of shared heritage rather than a political event, the exposition has already drawn large crowds of devotees, reinforcing the deep cultural and spiritual connections that link Sri Lanka and India by a Government that was once openly hostile to its northern neighbor before coming into power.

Colombo is currently witnessing a striking convergence of religion, diplomacy, and politics at the Gangaramaya Temple, where the sacred Devnimori Buddha Relics are on public display. Excavated in Gujarat and brought to Sri Lanka with full state honours, the relics are being exhibited for public veneration. President Anura Kumara Dissanayake inaugurated the exposition, underscoring its national and symbolic significance. Framed as a celebration of shared heritage rather than a political event, the exposition has already drawn large crowds of devotees, reinforcing the deep cultural and spiritual connections that link Sri Lanka and India by a Government that was once openly hostile to its northern neighbor before coming into power.

This ongoing event is not an isolated gesture. It forms part of a broader diplomatic reorientation that became especially visible during Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to Sri Lanka in 2025, which was framed under the theme “Friendship of Centuries, Commitment to a Prosperous Future.” Modi, together with President Dissanayake, paid homage at the Jaya Sri Maha Bodhi in Anuradhapura, deliberately anchoring contemporary diplomacy in a shared sacred geography. During the visit, President Dissanayake conferred upon Modi the Sri Lanka Mitra Vibhushana Award. Taken together, these acts suggest a conscious effort by the current Government to recast Sri Lanka–India relations not as a grudging necessity driven by economic crisis, but as a historically grounded partnership.

The significance of these acts becomes interesting when situated within Sri Lanka’s domestic context. The current Government, led by the National People’s Power (NPP) is a coalition in which the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) plays a decisive ideological role. Historically, the JVP viewed India with deep suspicion, portraying it as a regional hegemony and an external threat to Sri Lanka’s sovereignty. The fact that a Government shaped by this political tradition is now presiding over a phase of deepened cooperation with India marks a notable political realignment. The movement that once led an anti-state, anti-India insurrection in the late 1980s has adopted a markedly contradictory approach to regional geopolitics after coming into power. This was further underscored when JVP General Secretary Tilvin Silva, currently on a visit to India, met with India’s External Affairs Minister Dr. S. Jaishankar to discuss strengthening bilateral relations, growth opportunities, and social welfare initiatives, signaling a clear shift from the party’s earlier positions on India.

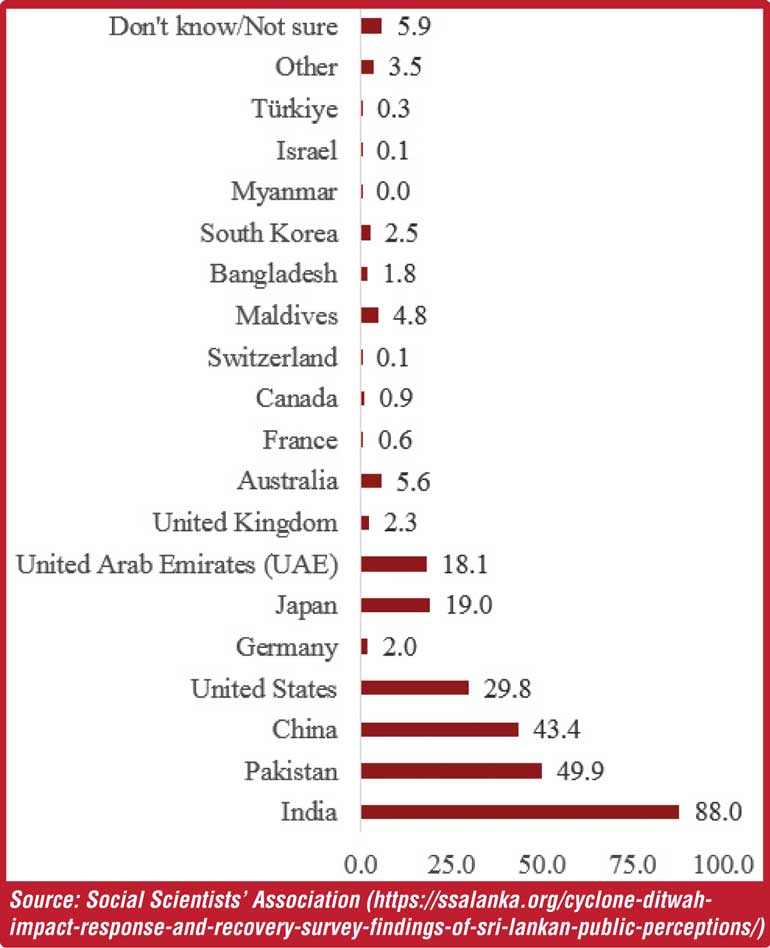

Importantly, this shift extends beyond the political sphere. Public opinion also appears to be moving decisively in favour of closer engagement with India. A recent countrywide public perception survey conducted by the Social Scientists Association reveals a marked transformation in how Sri Lankans view India’s role. When asked which country provided the most effective disaster relief following Cyclone Ditwah, an overwhelming 88% of respondents identified India. This response goes beyond immediate gratitude for humanitarian assistance; it reflects a broader public recognition of India as a reliable and responsive regional partner in moments of crisis.

Importantly, this shift extends beyond the political sphere. Public opinion also appears to be moving decisively in favour of closer engagement with India. A recent countrywide public perception survey conducted by the Social Scientists Association reveals a marked transformation in how Sri Lankans view India’s role. When asked which country provided the most effective disaster relief following Cyclone Ditwah, an overwhelming 88% of respondents identified India. This response goes beyond immediate gratitude for humanitarian assistance; it reflects a broader public recognition of India as a reliable and responsive regional partner in moments of crisis.

This popular recognition aligns closely with the material realities of Sri Lanka’s economic recovery. The renewed closeness with India carries significant economic and financial implications. In India’s 2026–27 budget, INR 4 billion was allocated specifically for Sri Lanka, representing a 33% increase over the previous year and signaling a sustained commitment that extends beyond episodic crisis support. For a small, crisis-hit economy like Sri Lanka, engagement with a rapidly growing Indian economy offers opportunities for recovery, investment, and infrastructure development. Hence, from a political economy perspective, India’s proximity could be less of a constraint and more of a prospect, but only if managed with careful strategy and foresight.

Survey findings suggest that public sentiment is broadly aligned with this recalibration. Sri Lankans appear to acknowledge India’s material assistance and to be largely receptive to the renewed partnership. The convergence of humanitarian aid, economic support, and shared cultural symbolism seems to have produced a level of public comfort with India that was far less evident in earlier decades. In this context, Buddhism has functioned as a morally coded, non-market language of partnership, one that helps soften the transactional nature of economic engagement and enjoys considerable popular legitimacy.

These dynamics, however, cannot be understood in isolation from the broader regional geopolitical context. At a time when India’s relations with several South Asian neighbours remain strained, maintaining stable and cooperative ties with Sri Lanka has become particularly important for India. Furthermore, India’s continued economic and diplomatic engagement with Sri Lanka must also be understood in the context of its efforts to counter China’s growing influence in South Asia and the Indian Ocean. Preventing Sri Lanka from getting close to China has therefore become a strategic priority for India, reinforcing its willingness to sustain assistance and engagement. This competitive regional environment, in turn, affords Sri Lanka a degree of bargaining space; one that can be used to diversify partnerships and negotiate terms more effectively.

Ultimately, the public recognition of India’s role after Cyclone Ditwah offers more than a snapshot of crisis-era goodwill. It signals a broader transformation in Sri Lanka’s political imagination, shaped by pragmatism, cultural familiarity, and economic necessity. The challenge ahead lies in sustaining this relationship in ways that preserve balance and choice, ensuring that cooperation does not harden into asymmetry. If navigated carefully, this emerging phase in Sri Lanka–India relations may succeed in aligning state strategy with popular sentiment. Survey findings indicate that public opinion may already be aligning in that direction.

Ultimately, the public recognition of India’s role after Cyclone Ditwah offers more than a snapshot of crisis-era goodwill. It signals a broader transformation in Sri Lanka’s political imagination, shaped by pragmatism, cultural familiarity, and economic necessity. The challenge ahead lies in sustaining this relationship in ways that preserve balance and choice, ensuring that cooperation does not harden into asymmetry. If navigated carefully, this emerging phase in Sri Lanka–India relations may succeed in aligning state strategy with popular sentiment. Survey findings indicate that public opinion may already be aligning in that direction.

(The author is a researcher at the Social Scientists’ Association. This article reflects her personal views. She can be reached via email at [email protected])

Colombo is currently witnessing a striking convergence of religion, diplomacy, and politics at the Gangaramaya Temple, where the sacred Devnimori Buddha Relics are on public display. Excavated in Gujarat and brought to Sri Lanka with full state honours, the relics are being exhibited for public veneration. President Anura Kumara Dissanayake inaugurated the exposition, underscoring its national and symbolic significance. Framed as a celebration of shared heritage rather than a political event, the exposition has already drawn large crowds of devotees, reinforcing the deep cultural and spiritual connections that link Sri Lanka and India by a Government that was once openly hostile to its northern neighbor before coming into power.

This ongoing event is not an isolated gesture. It forms part of a broader diplomatic reorientation that became especially visible during Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to Sri Lanka in 2025, which was framed under the theme “Friendship of Centuries, Commitment to a Prosperous Future.” Modi, together with President Dissanayake, paid homage at the Jaya Sri Maha Bodhi in Anuradhapura, deliberately anchoring contemporary diplomacy in a shared sacred geography. During the visit, President Dissanayake conferred upon Modi the Sri Lanka Mitra Vibhushana Award. Taken together, these acts suggest a conscious effort by the current Government to recast Sri Lanka–India relations not as a grudging necessity driven by economic crisis, but as a historically grounded partnership.

The significance of these acts becomes interesting when situated within Sri Lanka’s domestic context. The current Government, led by the National People’s Power (NPP) is a coalition in which the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) plays a decisive ideological role. Historically, the JVP viewed India with deep suspicion, portraying it as a regional hegemony and an external threat to Sri Lanka’s sovereignty. The fact that a Government shaped by this political tradition is now presiding over a phase of deepened cooperation with India marks a notable political realignment. The movement that once led an anti-state, anti-India insurrection in the late 1980s has adopted a markedly contradictory approach to regional geopolitics after coming into power. This was further underscored when JVP General Secretary Tilvin Silva, currently on a visit to India, met with India’s External Affairs Minister Dr. S. Jaishankar to discuss strengthening bilateral relations, growth opportunities, and social welfare initiatives, signaling a clear shift from the party’s earlier positions on India.

Importantly, this shift extends beyond the political sphere. Public opinion also appears to be moving decisively in favour of closer engagement with India. A recent countrywide public perception survey conducted by the Social Scientists Association reveals a marked transformation in how Sri Lankans view India’s role. When asked which country provided the most effective disaster relief following Cyclone Ditwah, an overwhelming 88% of respondents identified India. This response goes beyond immediate gratitude for humanitarian assistance; it reflects a broader public recognition of India as a reliable and responsive regional partner in moments of crisis.

Importantly, this shift extends beyond the political sphere. Public opinion also appears to be moving decisively in favour of closer engagement with India. A recent countrywide public perception survey conducted by the Social Scientists Association reveals a marked transformation in how Sri Lankans view India’s role. When asked which country provided the most effective disaster relief following Cyclone Ditwah, an overwhelming 88% of respondents identified India. This response goes beyond immediate gratitude for humanitarian assistance; it reflects a broader public recognition of India as a reliable and responsive regional partner in moments of crisis.

This popular recognition aligns closely with the material realities of Sri Lanka’s economic recovery. The renewed closeness with India carries significant economic and financial implications. In India’s 2026–27 budget, INR 4 billion was allocated specifically for Sri Lanka, representing a 33% increase over the previous year and signaling a sustained commitment that extends beyond episodic crisis support. For a small, crisis-hit economy like Sri Lanka, engagement with a rapidly growing Indian economy offers opportunities for recovery, investment, and infrastructure development. Hence, from a political economy perspective, India’s proximity could be less of a constraint and more of a prospect, but only if managed with careful strategy and foresight.

Survey findings suggest that public sentiment is broadly aligned with this recalibration. Sri Lankans appear to acknowledge India’s material assistance and to be largely receptive to the renewed partnership. The convergence of humanitarian aid, economic support, and shared cultural symbolism seems to have produced a level of public comfort with India that was far less evident in earlier decades. In this context, Buddhism has functioned as a morally coded, non-market language of partnership, one that helps soften the transactional nature of economic engagement and enjoys considerable popular legitimacy.

These dynamics, however, cannot be understood in isolation from the broader regional geopolitical context. At a time when India’s relations with several South Asian neighbours remain strained, maintaining stable and cooperative ties with Sri Lanka has become particularly important for India. Furthermore, India’s continued economic and diplomatic engagement with Sri Lanka must also be understood in the context of its efforts to counter China’s growing influence in South Asia and the Indian Ocean. Preventing Sri Lanka from getting close to China has therefore become a strategic priority for India, reinforcing its willingness to sustain assistance and engagement. This competitive regional environment, in turn, affords Sri Lanka a degree of bargaining space; one that can be used to diversify partnerships and negotiate terms more effectively.

Ultimately, the public recognition of India’s role after Cyclone Ditwah offers more than a snapshot of crisis-era goodwill. It signals a broader transformation in Sri Lanka’s political imagination, shaped by pragmatism, cultural familiarity, and economic necessity. The challenge ahead lies in sustaining this relationship in ways that preserve balance and choice, ensuring that cooperation does not harden into asymmetry. If navigated carefully, this emerging phase in Sri Lanka–India relations may succeed in aligning state strategy with popular sentiment. Survey findings indicate that public opinion may already be aligning in that direction.

(The author is a researcher at the Social Scientists’ Association. This article reflects her personal views. She can be reached via email at [email protected])