Friday Feb 13, 2026

Friday Feb 13, 2026

Friday, 12 January 2024 00:25 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

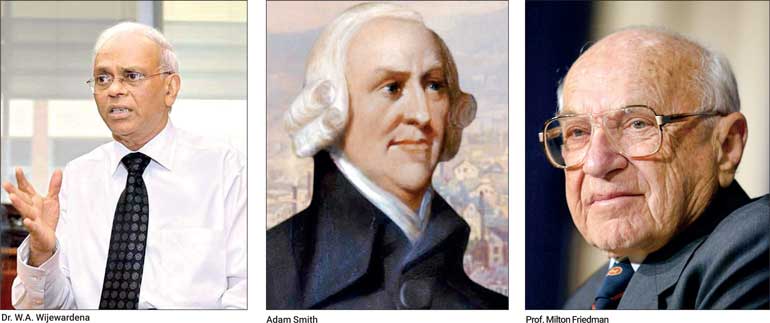

This article is part appreciation and part analysis. It is a direct thank you and tribute to the Daily FT’s regular columnist, former Deputy Governor of the Central Bank, Dr. W.A. Wijewardena. I have been reading his columns for almost as long as he has been writing them; Dr. Wijewardena always brings a nuanced perspective to Sri Lanka’s economic matters.

This article is part appreciation and part analysis. It is a direct thank you and tribute to the Daily FT’s regular columnist, former Deputy Governor of the Central Bank, Dr. W.A. Wijewardena. I have been reading his columns for almost as long as he has been writing them; Dr. Wijewardena always brings a nuanced perspective to Sri Lanka’s economic matters.

In an article published on 1 January: “Still Batting and not out yet” that notes his 13th year in publishing this regular column, Dr. Wijewardena seems to be in good form and I would urge anyone with a passing interest in economics to pay close attention to it.

At the outset he notes that the tagline of his column is derived from his belief that economics is “relevant to every matter and hence, every issue could be looked through the eyes of an economist. Hence, the topics covered included not only those in pure economics, but also those relating to political economy and literature.” Notice that Dr. Wijewardena makes a clear acknowledgement that economics does not exist in a vacuum, that it interacts with politics and hence includes a social dynamic with foundations in philosophy.

Here, Dr. Wijewardena is clear on how he perceives the ‘first principles’ of economics, those which will be familiar to the reader: concepts like scarcity, market forces of supply and demand, opportunity costs, all of which interact to produce some form of efficient allocation of resources and the outcomes of such allocations. In Dr. Wijewardena’s article, he notes that the ideology he uses is based on the tendencies of the “economic man, the selfish, own-utility maximising” ideal; that individuals following their own self-interest generate favourable or positive outcomes for society without intending to. Dr. Wijewardena refers to the ‘invisible hand’ of Adam Smith, the “father of economics in the

modern era.”

A crucial caveat is introduced by Dr. Wijewardena to this “selfish, economic man” noting Smith’s lesser-known work: “The Theory of Moral Sentiments”, published before the “Wealth of Nations”. Here, Smith’s selfish man also seems to admit some personal pleasure from the development of others; while we derive most pleasure from our own personal development, we accept in some form, happiness from the advancement of our fellow human beings. What Smith refers to as “pity” or “compassion” is what Dr. Wijewardena calls the “built-in ambivalence of Homo-sapiens” noting that therefore, the “economic man is not a pure selfish person”.

Here the word ‘ambivalence’ suggests a confusion or contradiction, however this is not the best descriptor; human beings negotiate an internal balance between what is best for themselves, their dependencies, immediate environment, their neighbour and for society as a whole. Evolutionary psychology, for instance, suggests that human behaviours evolved to enhance prospects for survival and prosperity as social beings, producing an inherent understanding that cooperation and social norms contribute to overall well-being. In his book, “The Selfish Gene”, Richard Dawkins discusses altruism from an evolutionary perspective; similarly, Robert Trivers emphasised the theory of ‘reciprocal altruism’ which promotes the idea that behaviours have evolved to promote group cohesion.

The great precept of nature

It is worth considering Adam Smith’s idea of what drives individual economic perspectives and how these manifest in an economic arrangement, how or why this “selfish economic man” moderates their desires with “ambivalence”. To give its full title: The Theory of Moral Sentiments; or, “An Essay Towards an Analysis of the Principles by which Men Naturally Judge Concerning the Conduct and Character, First of Their Neighbours, and Afterwards of Themselves”.

It is worth considering Adam Smith’s idea of what drives individual economic perspectives and how these manifest in an economic arrangement, how or why this “selfish economic man” moderates their desires with “ambivalence”. To give its full title: The Theory of Moral Sentiments; or, “An Essay Towards an Analysis of the Principles by which Men Naturally Judge Concerning the Conduct and Character, First of Their Neighbours, and Afterwards of Themselves”.

In Chapter 1: “OF Sympathy” from “Section 1: “Of the Sense of Propriety”: Smith is trying to explain how a human being is able to feel sympathy for another, considering that we can have no “immediate experience of what other men feel” we can thus form “no idea of the manner in which they are affected, but by conceiving what we ourselves should feel in the like situation. Though our brother is upon the rack, as long as we ourselves are at our ease, our senses will never inform as of what he suffers… it is by the imagination only that we can form any conception of what are his sensations… His agonies, when they are thus brought home to ourselves, when we have thus adopted and made them our own, begin at last to affect us, and we then tremble and shudder at the thought of what he feels.”

In Chapter 5 of the same section, titled “Of the Amiable and Respectable Virtues”, Smith describes his ideal of humanity: “And hence it is, that to feel much for others, and little for ourselves, that to restrain our selfish, and to indulge our benevolent, affections, constitutes the perfection of human nature; As to love our neighbour as we love ourselves is the great law of Christianity, so it is the great precept of nature to love ourselves only as we love our neighbour…”

In ‘Moral Sentiments’ Smith introduces us to his concept of the “Impartial Spectator”; described as emphasising the rational and reasoned moral assessment of a given situation or incident. Smith notes the necessity to remove ourselves from feelings of being affected: “But we admire that noble and generous resentment which governs its pursuit of the greatest injuries, not by the rage which they are apt to excite in the breast of the sufferer, but by the indignation which they naturally call forth in that of the impartial spectator; which allows no word… to escape it beyond what this more equitable sentiment would dictate…nor desires to inflict any greater punishment, than what every indifferent person would rejoice to see

executed…”

These are just some examples of what Smith thought of humanity’s inclinations to morality, that concerns of equity and justice and proportionality were inherent to the human psyche. Adam Smith was a key figure of the Enlightenment era that lays the philosophical foundations for economics. The essence of humanity and its impacts upon the societies we create were matters of great consequence to such enlightenment thinkers. Jean-Jacques Rousseau wrote about how social structures impacted human nature, before him, Hobbes’ ‘Leviathan’ discussed the social contract and the principles of mutual protection and cooperation.

Free to choose

Let us contrast this to a more modern perspective of a particular branch (and brand) of economics and how it utilises Adam Smith and the “selfish” economic man while disregarding the moral foundations that he observed as governing the intentions and actions of men (market participants).

Prof. Milton Friedman, a Nobel Prize winner, is one of modern history’s most prominent economists, dominating the field in the 1970s and ‘80s, advising American Presidents and foreign governments. Friedman has been credited with (or blamed for) installing the free-market principles that he considered to be essential to maximising the positive effects of capitalism. Friedman echoed the aforementioned “selfish man” and positive contingencies of his utility-maximising pursuit of self-interest. There is a certain villainous quality attributed by some to Friedman’s policy protocols and their foundational values, something I will try to avoid.

Prof. Milton Friedman, a Nobel Prize winner, is one of modern history’s most prominent economists, dominating the field in the 1970s and ‘80s, advising American Presidents and foreign governments. Friedman has been credited with (or blamed for) installing the free-market principles that he considered to be essential to maximising the positive effects of capitalism. Friedman echoed the aforementioned “selfish man” and positive contingencies of his utility-maximising pursuit of self-interest. There is a certain villainous quality attributed by some to Friedman’s policy protocols and their foundational values, something I will try to avoid.

Instead, I will simply present some aspects of his doctrine. Friedman is closely associated with Friedrich von Hayek, and follows this school of limited government which, according to the Friedman doctrine, limits the freedom of individuals to choose their own destiny, as it were. Thus, Friedman does not support social welfare or a safety-net but has at various times in his career, supported a negative income tax (cash transfers from the state), most famously under the Nixon administration. Friedman is thus elusive: in Capitalism and Freedom (1962) he notes that “the existence of a free market does not of course eliminate the need for government. On the contrary, government is essential both as a forum for determining the “rules of the game” and as an umpire to interpret and enforce the rules decided on. What the market does is to reduce greatly the range of issues that must be decided through political means, and thereby to minimise the extent to which government need participate directly in the game… It is this feature of the market that we refer to when we say that the market provides economic freedom.”

Friedman has also discussed the links, as he saw them, between political freedom and economic freedom, stating that “Political freedom means the absence of coercion of a man by his fellow men. The fundamental threat to freedom is power to coerce, be it in the hands of a monarch, a dictator, an oligarchy, or a momentary majority. The preservation of freedom requires the elimination of such concentration of power to the fullest possible extent… By removing the organisation of economic activity from the control of political authority, the market eliminates this source of coercive power. It enables economic strength to be a check to political power rather than a reinforcement” (Capitalism and

Freedom – 1962).

Rationality and self-interest

It is left to the reader to analyse the short- and long-term outcomes of Friedman’s various projects of consultancy to world leaders and governments, some directly, others through the Mont Pellerin Society: the Reagan and Thatcher eras; Chile in the 70’s; Russia and Poland, post-USSR. Whatever the judgement of these outcomes and whatever characteristics of Friedman’s and by extension Adam Smith’s philosophies might be attributed to those outcomes, it is important to note that even Friedman was not preaching an economic doctrine that was value neutral, in fact he had a very clear hierarchy of values, with personal freedom at the very top.

Ultimately, in the same way that rationality does not always reflect self-interest, the study of economics cannot be value neutral and thus neither can economic policy. Policy generates something like a system, the outcomes of that system will imply some set of explicit and implicit values, derived from some hierarchy of priorities.

Ultimately, in the same way that rationality does not always reflect self-interest, the study of economics cannot be value neutral and thus neither can economic policy. Policy generates something like a system, the outcomes of that system will imply some set of explicit and implicit values, derived from some hierarchy of priorities.

All this is the necessary basis to accept the claim that economic policy makes trade-offs, with implicit and explicit value judgements. Every time we view a policy, we ought to acknowledge its underlying values and the outcomes this policy is striving to attain, outcomes that can be measured. The United Nations Development Programme Report from a few weeks ago showed the levels of economic disparity and inequality in Sri Lanka, ranking our country as one of the top 5 most unequal countries in the Asia Pacific. It further noted that the top 1% of Sri Lanka’s income deciles own 30% of total private wealth and the bottom 50% own less than 3%.

This is how we have organised our economic system and society, it also seems to be how we have continued in the wake of a financial and economic collapse brought about by policy failures, through negligence and short-termism. What do these outcomes and results say about our value systems and morality, what does it reflect? What does the commentary and the way we discuss issues like poverty, distress, inflation, stability inform us about the system we exist in?

Think back to Dr. Wijewardena’s “eyes of an economist”: an economist is a person with perspective that might well be distinct but is still grounded in some set of first principles; a value system, through which they propose policy and measure its outcomes. What would Adam Smith and the enlightenment thinkers have to say about Sri Lanka’s policy outcomes and how might they differ from Milton Friedman? Some might wonder how economics and humanity have travelled so far and yet achieved

so little.

(The writer has 15 years of experience in the Financial and Corporate sectors after completing a Degree in Accounting and Finance at the University of Kent (UK) while also completing a Masters in International Relations from the University of Colombo. He is a media resource-person, presenter, political commentator and researcher. He also presents an interview show that is available on Instagram, Facebook and YouTube. He is also a member of the Working Committee of the Samagi Jana Balawegaya (SJB). He can be reached via email: [email protected];

twitter: @kusumw.)