Thursday Mar 12, 2026

Thursday Mar 12, 2026

Tuesday, 6 January 2026 01:07 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

When recent cyclones disrupted livelihoods, supply chains, and regional economies, banks were once again expected by those affected to step in—grant moratoria, restructure loans, and extend fresh credit—often precisely when risks were peaking. This recurring pattern, seen during the pandemic and the economic crisis, exposes a hard reality: not all banks have the Balance-Sheet strength to play a counter-cyclical role when the economy needs them most.

When recent cyclones disrupted livelihoods, supply chains, and regional economies, banks were once again expected by those affected to step in—grant moratoria, restructure loans, and extend fresh credit—often precisely when risks were peaking. This recurring pattern, seen during the pandemic and the economic crisis, exposes a hard reality: not all banks have the Balance-Sheet strength to play a counter-cyclical role when the economy needs them most.

This strengthens the case for market-driven consolidation among Sri Lanka’s mid-sized and smaller licenced banks. Consolidation is not about size for its own sake, nor about reducing competition. It is about building institutions with sufficient capital, governance depth, and operational resilience to absorb shocks and continue lending through economic cycles.

Sri Lanka is a small, open economy repeatedly exposed to external shocks—global interest-rate cycles, trade disruptions, geopolitical developments, and increasingly frequent climate-related disasters. Banks without scale struggle to absorb these shocks without curtailing lending or weakening Balance Sheets. The economic crisis revealed these structural vulnerabilities, particularly among institutions with limited capital buffers and constrained access to funding.

The Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL) has responded by proposing a framework to strengthen financial system stability and address the long-term viability of weaker banks. Under this framework, banks with assets below Rs. 400 billion will be evaluated bi-annually, with regulatory intervention where underperformance persists. The objective is clear: to ensure that banks operating in Sri Lanka are resilient enough not to become a source of systemic stress.

Consolidation is not about size for its own sake, nor about reducing competition. It is about building institutions with sufficient capital, governance depth, and operational resilience to absorb shocks and continue lending through economic cycles

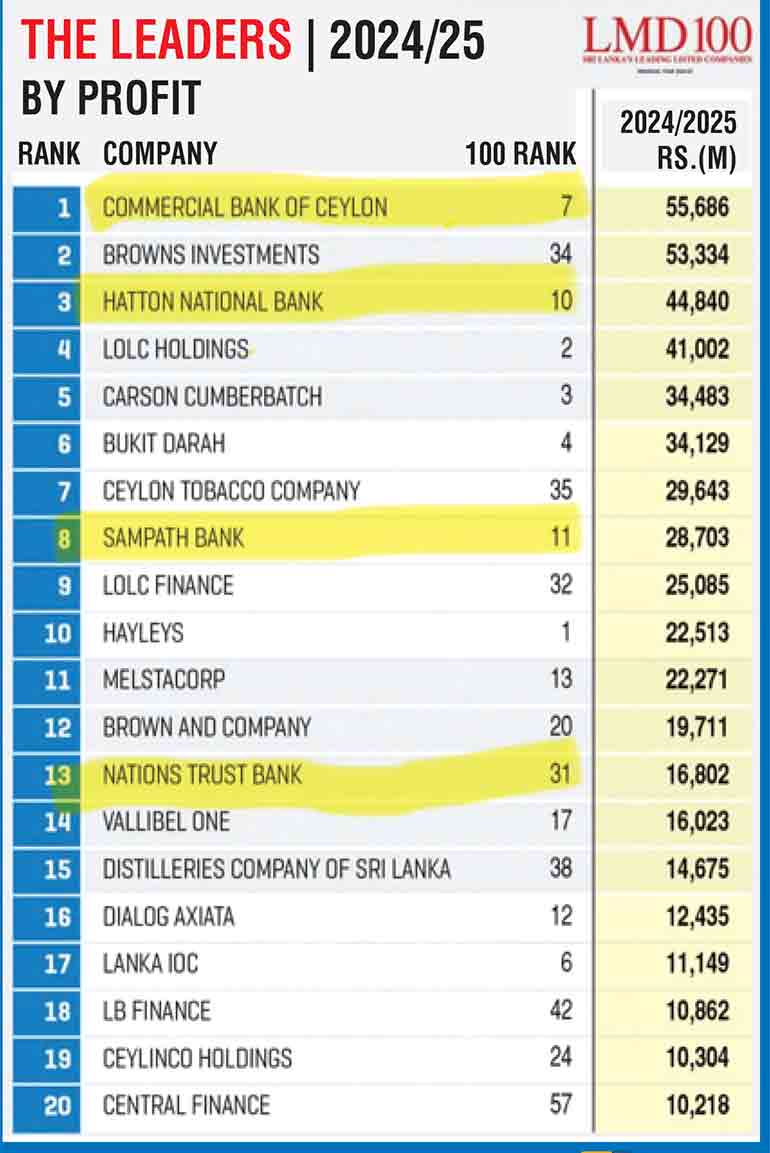

Performance of banks in 2025

According to CBSL data for the nine months ended September 2025 (Q3 2025), the sector showed a cyclical recovery. Total assets grew by 16% year-on-year to Rs. 24.5 trillion, while Profit After Tax rose to Rs. 279 billion. Capital adequacy and liquidity remained comfortable.

These headline figures, however, mask sharp differences beneath the surface. Smaller and mid-sized banks continue to face higher funding costs, weaker capital generation, and limited capacity to invest in technology, risk systems, and human capital.

An important emerging pressure point is the use of counter-cyclical capital buffers (CCyB). As credit growth picks up, regulators require banks to build additional capital buffers to prepare for future downturns. For large banks, this typically means retaining earnings for a few quarters.

For smaller banks, it can mean raising fresh capital at unfavourable valuations or cutting back lending to remain compliant. In effect, what is manageable for large banks can become a binding constraint for smaller ones—making consolidation a rational strategic response rather than a defensive one.

Indian experience

India’s experience offers useful but nuanced lessons. Between 2019 and 2020, the Government of India, working with the Reserve Bank of India, consolidated multiple medium-sized public sector banks, reducing their number from 27 to 12. The objectives were capital conservation, stronger Balance Sheets, and improved lending capacity.

These goals were broadly achieved, with larger banks better positioned to support infrastructure and corporate financing. However, the process also involved branch rationalisation, staff redeployment, and concerns about access in some rural areas. The lesson is not blind replication, but recognition that consolidation delivers benefits only when its social and economic trade-offs are actively managed.

Banking sector consolidation should not be viewed as an admission of weakness, but as a strategic response to a more volatile world

Human resources and inclusion

This brings us to the most sensitive issue: people. Consolidation affects employees, branch networks, and customers. Poorly managed mergers can disrupt service and weaken trust. Yet fragmentation also carries costs. Weak banks are less able to support SMEs, agriculture, and regional economies during downturns.

The policy challenge is not whether consolidation should occur, but how to ensure it strengthens financial inclusion rather than undermines it. Regulatory safeguards, transition planning, and clear communication are essential.

Concerns about “too big to fail” and reduced competition are legitimate. The global financial crisis demonstrated the dangers of large, interconnected institutions. Sri Lanka must guard against this through higher capital surcharges for systemically important banks, credible resolution frameworks, and strong supervision. Competition concerns should be addressed by keeping consolidation market-driven, transparent, and complemented by innovation—particularly through digital banking and fintech partnerships that expand choice rather than restrict it.

A recommendation made by a committee as far back as 2015—that consolidation should be market-led, not administratively imposed—remains relevant today. The role of the State and regulator is to create clear rules, credible resolution mechanisms, and capital frameworks that allow markets to make rational decisions. India’s experience shows the value of coordination, but Sri Lanka’s context calls for restraint rather than directive mergers

Conclusion

A recommendation made by a committee as far back as 2015—that consolidation should be market-led, not administratively imposed—remains relevant today. The role of the State and regulator is to create clear rules, credible resolution mechanisms, and capital frameworks that allow markets to make rational decisions. India’s experience shows the value of coordination, but Sri Lanka’s context calls for restraint rather than directive mergers. Banking sector consolidation should not be viewed as an admission of weakness, but as a strategic response to a more volatile world. Climate shocks, regulatory tightening, and global uncertainty demand banks that are resilient, well-capitalised, and operationally strong. The real choice is not between consolidation and competition, but between fragility and resilience. Thoughtfully executed, market-driven consolidation can strengthen Sri Lanka’s banking system—and its capacity to support sustainable growth—before the next crisis arrives.

The policy challenge is not whether consolidation should occur, but how to ensure it strengthens financial inclusion rather than undermines it

References