Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Monday, 6 June 2022 00:44 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Figure 4. Sustainable Banking Network Global Meeting, 2019

From left: IFC Country Manager of Sri Lanka and Maldives Amena Arif, National Bank of Georgia Deputy Governor Archil Mestvirishvili, MIGA Vice President Ethiopis Tafara, Association of Banks in Cambodia Sustainable Finance Committee Chair, FTB Deputy General Manager/Chief Risk Officer Lay Rachana, Central Bank of Sri Lanka Governor Dr. P. Nandalal Weerasinghe, National Bank of Cambodia Director General Serey Chea, IFC Senior Manager Jan Van Bilsen, and IFC Country Manager of Cambodia Kyle Kelhofer

As a layman in the subject of political economy nonetheless interested in discerning the real background to the historic debt crisis that Sri Lanka is undergoing at present, I have been reading many reports including expert views, opinion statements, institutional press releases, think-tank analyses, COPE reports, etc. that are plentiful on the internet. Based on these readings, I was able to synthesise a layman’s review which I thought of putting out to a wider readership to stimulate constructive discourses from the more knowledgeable authorities and others alike, especially on the solutions that are available for our country to come out of this huge debt crisis.

As a layman in the subject of political economy nonetheless interested in discerning the real background to the historic debt crisis that Sri Lanka is undergoing at present, I have been reading many reports including expert views, opinion statements, institutional press releases, think-tank analyses, COPE reports, etc. that are plentiful on the internet. Based on these readings, I was able to synthesise a layman’s review which I thought of putting out to a wider readership to stimulate constructive discourses from the more knowledgeable authorities and others alike, especially on the solutions that are available for our country to come out of this huge debt crisis.

One of the major criticisms of the general public is that although warnings of this impending disaster had been made repeatedly at official meetings among technocrats and bureaucrats, the general public was not sufficiently alerted and forewarned early enough especially via popular media to shake up the bureaucracy to make a timely course correction.

We all are now aware that Sri Lanka has an accumulated foreign debt of $ 51 billion at the time of pre-emptive sovereign default of foreign currency repayment which happened in March/April 2022.

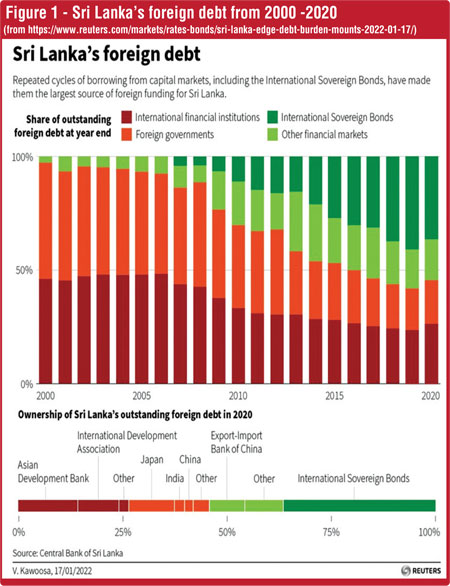

Figure 1 with a series of histograms that appeared on the web provides a relatively easy understanding of the progression of our cumulated foreign debt over the years since 2000 and its proportional ownership of creditors/lenders. It had been prepared by Reuters in January 2022 sourcing Central Bank information and colour-coded to apportion the foreign debt accumulated since 2000. The proportional ownership has been grouped into several categories of lenders in this chart such as International Financial Institutions (IDA, ADB, etc. in red), foreign governments (Japan, China, India, etc. in orange), International Sovereign Bond Issuers (Goldman Sachs, Black Rock, and Pacific Investment Management, Vanguard, etc. in green!) and other capital market lenders (Exim banks etc. in pale green).

This figure reveals that a higher proportion of foreign funding for Sri Lanka’s development projects as well as to bridge the annual budget deficits in the early 2000 period came via bilateral and multilateral donor contributions (red and orange colour codes), when Sri Lanka was still a Lower Middle-Income Country (LMIC). However, this trend has been changing since 2007 or so, when Sri Lanka started obtaining loans at relatively higher interest rates from International Sovereign Bonds (ISBs) and other Financial Capital Markets. The contribution of ISBs increased significantly from around 2015 and reached an all-time high in 2019 almost at the same time when Sri Lanka was elevated to an Upper Middle-Income category (UMIC) for a short period of time by the World Bank.

However, a year later Sri Lanka was down-graded again as a lower-middle income country after it recorded a $ 4,020 per capita income for 2020. Apparently, when a country reaches an Upper Middle-Income level, it is not entitled to concessionary loans but must seek funding from International Capital Markets at the internationally prevailing competitive interest rates. Sri Lanka’s access to international capital markets (with International Sovereign Bonds issuances since 2007) brought a shift to commercial borrowing and an increase in external interest rates to be paid back in short periods of time.

Consequently, Sri Lanka’s foreign debt apportioning in 2022, as per Figure 1 which has been computed using information from Sri Lanka’s Central Bank indicates that over 35% of the island’s debt is owned by US and UK-based ISBs. The balance of foreign debt in 2022 is owned by the aforesaid bi-lateral and multilateral agencies. Some of these latter agencies, usually charge lower interest rates on concessionary terms. They have even gone to the extent of being more compassionate to express their willingness to further delay the debt repayment while at the same time being charitable enough to donate humanitarian aid in the form of food, fuel, and medicine during this crisis period. It is clear that the root cause of Sri Lanka’s default at this time is due to the disproportionate accumulation of ISBs and other such financial instruments in recent times. Higher interest rates over short periods of time needed to be paid, for refinancing the loans already taken.

This annual progression of the ‘sovereign debt trap’ also led to the speculation of unsustainability of Sri Lanka’s foreign debt from 2019 onwards leading to a progressive downgrading of credit ratings by the three leading credit rating agencies – Moody’s Investor Services, Standard and Poor’s (S&P), and the Fitch Group. This downgrading by credit rating agencies further deepened Sri Lanka’s debt crisis pushing us into one of the worst economic crises in modern history. The Verite Research Strategic Analysis Working Paper published in October 2021provides an analysis on this. For the five years from 2021 to 2025, the annual average repayments due on servicing external debt maturities is $ 4,400 million. In contrast, from 2015 to 2018, the Government only had to repay an annual average of $ 2,700 million as external debt repayment. To meet those debt repayments, during 2015 to 2018, the Government borrowed on average $ 1,900 million through ISBs in a year as indicated in Figure 1.

Since the beginning of 2020, the yields of ISBs have more than doubled and the credit ratings of the sovereign bonds were also downgraded multiple times in 2020 leading to high risks of default in 2021 preventing further borrowing from the international markets. This forced the government to use its already depleting reserves to meet the external debt obligations, while at the same time, meeting the urgent healthcare emergencies resulting from the rapid spread of COVID-19 pandemic which demanded lockdowns over months, associated economic losses and also for meeting increasing healthcare needs.

While it has been widely reported in the Western media that Sri Lanka is a victim of a ‘Chinese debt trap’, our increased dependency on International Sovereign Bonds over recent times is also equally, if not more, responsible for the default at this time as Sri Lanka has been compelled to borrow money from international capital markets at higher rates to be paid back over short periods of time. These funds were needed for the repayment of the loans already taken for the settlement of earlier taken loans/their interests while providing at the same time, the shortfall of social welfare benefits from the lost tax revenue as a result of ill-advised tax rebates granted in 2019. The resultant drop in revenue amounted to 3% of GDP – from 12.6% in 2019 to 9.2% in 2020. The revenue as a share of GDP for 2020 has apparently been the lowest in the post-independence history of Sri Lanka that led to huge deficits which need to be financed through borrowing, resulting in increasing debt.

Notwithstanding some of these unanticipated debilitating economic cataclysms, some political analysts speculate whether Sri Lanka was duped into a situation of ‘pumped and dumped’ by the Western interests. The World Bank up-graded Sri Lanka to a Lower Middle-Income Country (LMIC) in 1997, and then to the short-lived Upper Middle-Income Country in 2019 thus making it ineligible for lower interest rates for national development thus compelling to borrow from International Capital Markets. This fortuitously coincided with the 2019 Easter Sunday bombing spree which started the rapid downward spiralling of Sri Lanka’s economy.

Notwithstanding some of these unanticipated debilitating economic cataclysms, some political analysts speculate whether Sri Lanka was duped into a situation of ‘pumped and dumped’ by the Western interests. The World Bank up-graded Sri Lanka to a Lower Middle-Income Country (LMIC) in 1997, and then to the short-lived Upper Middle-Income Country in 2019 thus making it ineligible for lower interest rates for national development thus compelling to borrow from International Capital Markets. This fortuitously coincided with the 2019 Easter Sunday bombing spree which started the rapid downward spiralling of Sri Lanka’s economy.

On top of these, internal mismanagement of our economy also has contributed in no small measure to this predicament. The infamous bond scams, unbridled corruption and nepotism at the highest levels, imprudent decisions of the then monitory board of the Central Bank, and more significantly, holding on to such irrational decisions for a long period thus bleeding our foreign exchange reserves by over $ 5.5 as reported by one of its members at a recent COPE meeting.

So, it surmises that both external interventions as well as internal economic mismanagement has contributed to the present-day debt crisis leading to ‘Arab Spring’ style protests by segments of the general public fuelled by opportunistic politicians and their invisible handlers. It has been transmitted in some academic fora that Sri Lanka’s default seemed to follow a systematic, deliberate, and planned route to haul Sri Lanka into IMF’s and Washington’s clutches. This likelihood had apparently been in the air for some time – at least since the rejection of the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) compact by the Sri Lankan Government in December 2019.

The MCC compact for Sri Lanka was designed to reduce poverty through improved transportation network and providing secure land titles to small holder farmers and other Sri Lankan landholders. The Special Presidential Commission Report which examined the draft MCC Compact has recommended the rejection of the Compact in its current form as it not only imperils Sri Lanka’s economic sovereignty but also undermines the land and human rights of her citizens. We need to be vigilant at this stage at which we are in a desperate situation in meeting day to day needs of the people as well as fulfilling debt obligations through their restructuring. There are indications that a number of stealthy moves are already at play to undermine the rights of the people (see recent press releases by Dr. Gunadasa Amarasekera of the Federation of National Organizations).

Some political analysts argue that this ‘staged default’ would enable the IMF to effectively take control of strategic geopolitical positioning by influencing Sri Lanka’s economic policy initiatives compromising its sovereignty. It is also speculated that by doing so, they can stave off the Chinese influence (despite China being a leading member of the IMF) and more significantly, make it difficult for Sri Lanka to source its oil, gas and other energy requirements at discounted rates from sanctions-hit Russia.

Ironically, India continues to avail themselves to the discounted oil and gas supplies from Russia despite some resistance from her western partners while helping to meet our energy needs through loans and grants. It is a pity that Sri Lanka is far too late in looking into this possibility of negotiating with Russia directly for supplementing our long-term fossil fuel and other energy needs in exchange for our tea exports.

Sri Lanka is apparently caught between the devil and the deep blue sea for being located in a geostrategic position abundantly endowed with strategically important natural resources. While being at the centre of the Indian Ocean Sea Lanes of Communication (SLOC) with an extensive ocean and land-based mineral resources including premium grade graphite and rare earth elements, some political analysts are of the view that Sri Lanka suffers from a ‘Paradox of Plenty’ or perhaps, a geostrategic ‘Resource Curse’. This phenomenon often afflicts countries blessed with abundant natural resources, like Sri Lanka.

According to the Global Wealth Databook 2020 of the Credit Suisse Research Institute, the total wealth of Sri Lanka is estimated to be $ 351 billion while admitting at the same time that the quality of wealth data used for this estimation to be poor. A more realistic estimate could indeed yield even a higher value and Sri Lanka appears to be far from bankrupt, on that count. Despite all these, we have been having a slower economic development prone to poor governance, corruption and cronyism over successive political regimes since independence. This economic wealth of Sri Lanka may be a key constituent put on offer in attracting creditors to our national-scale real estate assets at this crucial stage of negotiations for debt relief.

The US ambassador to Sri Lanka and the Maldives, Julie Chung, in a recent press release remarked that Sri Lanka is at the heart of the Indo-Pacific oceanscape, sitting next to some of the world’s busiest shipping lanes through which about half the world’s container ships and two-thirds of the world’s oil shipments pass. According to her, Sri Lanka has the potential to play a pivotal role in the health of world trade. It is not surprising, therefore, the former US Under Secretary for South and Central Asia, Alice G.

Well, a few years ago called Sri Lanka a ‘valuable piece of real estate’ in the Indian Ocean. Still others have termed Sri Lanka ‘an unsinkable aircraft carrier’ in the Indian Ocean – much more strategic than the Chargos Island which was handed back to the people of Mauritius by the British (and hence US occupation ended) in February 2019 after the International Court of Justice in the Hague ruled that the latter’s occupation of Chargos Island was illegal under International Law.

Furthermore, it was none other than the US Secretary Blinken who had recently reported that in today’s world, cyberspace and cyber security are increasingly important and, as part of their vision for the Indo-Pacific, the United States looks to coordinate with partners to ensure an open and secure internet and to implement a framework for responsible behaviour in cyberspace.

With a background of this politico-geostrategic wealth, the Sri Lanka Government is up against tough bargaining with the IMF and their designated creditors to raise $ 8-12 billion or perhaps even more from the lease or sale of at least some of these valuable ‘real estate’ assets belonging to the people of Sri Lanka which have been grossly mismanaged over decades by successive governments. Dr. Nishan De Mel of Verite Research says, “When the IMF determines that a country’s debt is not sustainable, the country needs to take steps to restore debt sustainability prior to IMF lending.” These steps would undoubtedly feel quite painful in particular to the poorest and most vulnerable sectors of the country.

Prime Minister Wickremesinghe recently stated in the Parliament that SriLankan Airlines with all its assets would be the first to be privatised to relieve the debt burden. Among the other valuable public assets that are being considered to go under the hammer according to reports on the web are Mattala and Ratmalana airports, Sri Lanka Telecom shares, and the Sri Lanka Insurance Corporation to name a few. Then there are physical assets like Sri Lanka’s marine Exclusive Economic Zone which include the already identified oil and gas deposits, Under-sea Data Cable Routes, the strategic island’s telecom frequencies important for cyber-security.

These are a part of this ‘real estate’ package – the cynosure of many powerful global political players backed by leading international financiers – up for negotiations in the name of debt restructuring. Some economists are of the opinion that divesting these strategic public assets resulting from mismanagement, corruption, and ignorance of the potential value of these resources, is tantamount to throwing the baby with the bath water!

The debt restructuring and bridge financing negotiations with the IMF, if successful, may be able to provide us short-term debt relief tied with very stringent conditions such as tightening our monitory policy, raising taxes, reduction of Government expenditure and wastage, introducing a fuel and utilities pricing formula reflecting the market prices, among others. Although Sri Lanka promised a number of similar adjustments in during earlier rounds of negotiations with the IMF (in 2009 and 2016), none of them were implemented in full as planned since these would have resulted in high social and political costs.

With such a track record, the conventional IMF debt restructuring formula may not help to overcome our efforts in moving toward bridging the trade deficit. This is primarily because Sri Lanka continues to spend more foreign exchange than its receipt of revenue through the export of goods and services. This indeed has been the root cause of our long-term external debt problem. Economists argue that going to the IMF alone will not fix this problem. According to them, the IMF will simply put a sticking plaster on our arterial wound and send us home. If Sri Lanka continues haemorrhaging foreign exchange with its typical laissez-faire approach, we may have to go back again to the IMF in two years’ time asking for yet more debt relief!

To be continued

(The writer is a member of the Sustainable Development Council and can be contacted at [email protected].)