Thursday Mar 12, 2026

Thursday Mar 12, 2026

Monday, 26 January 2026 03:37 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

View of Prof. G.L. Peiris is, with respect, wrong on both constitutional principle and policy. There are no constitutional restraints on the judicial review of Executive action in relation to declarations of emergency. Self-imposed judicial restraint may well constitute an abdication of judicial responsibility

View of Prof. G.L. Peiris is, with respect, wrong on both constitutional principle and policy. There are no constitutional restraints on the judicial review of Executive action in relation to declarations of emergency. Self-imposed judicial restraint may well constitute an abdication of judicial responsibility

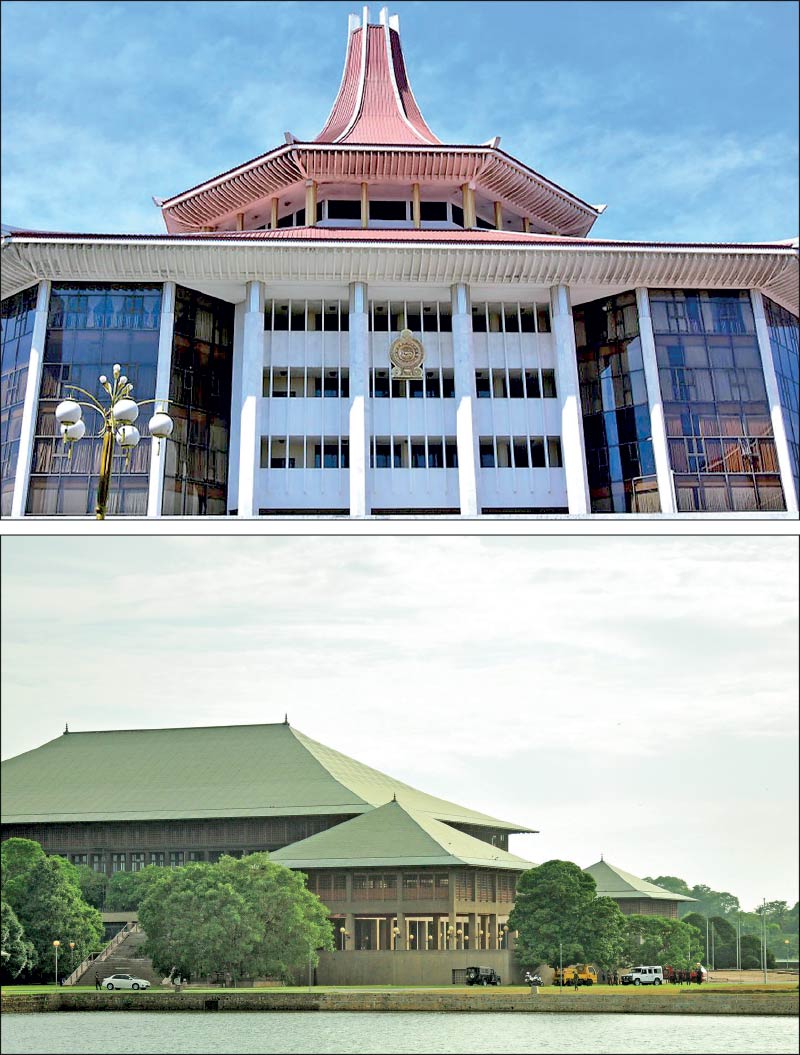

Professor G.L. Peiris (Prof. GLP) in a speech delivered on 12 December 2025 at the International Research Conference at the Faculty of Law, University of Colombo published in the Daily FT of 15 December 2025 under the caption “Presidential authority in times of emergency – A contemporary appraisal” has critiqued the majority judgment of the Supreme Court of Sri Lanka in Ambika Sathkunanathan V. A.G. on the declaration of emergency by Ranil Wickremasinghe as Acting President on 17 July 2022 in response to the “Aragalaya”. The majority held that Wickremasinghe had violated the Fundamental Rights of the people by a Declaration of a state of emergency. The author was to attend this event but was unable to do so due to a professional commitment out of Colombo.

Professor G.L. Peiris (Prof. GLP) in a speech delivered on 12 December 2025 at the International Research Conference at the Faculty of Law, University of Colombo published in the Daily FT of 15 December 2025 under the caption “Presidential authority in times of emergency – A contemporary appraisal” has critiqued the majority judgment of the Supreme Court of Sri Lanka in Ambika Sathkunanathan V. A.G. on the declaration of emergency by Ranil Wickremasinghe as Acting President on 17 July 2022 in response to the “Aragalaya”. The majority held that Wickremasinghe had violated the Fundamental Rights of the people by a Declaration of a state of emergency. The author was to attend this event but was unable to do so due to a professional commitment out of Colombo.

After citing authority from several foreign jurisdictions in support of his view of judicial deference to the Executive on matters relating to a state of emergency, he advances as one of the grounds as to why the majority were wrong in the Sri Lankan context is that the predisposition to judicial deference is reinforced by a firmly entrenched constitutional norm - “a foundational principle of our public law is the vesting of judicial power not in the courts but in parliament, which exercises judicial power through the instrument of the courts. This is made explicit by Article 4(c) of the constitution which provides “the judicial power of the People shall be exercised by Parliament through courts, tribunals and institutions created and established, or recognised by the Constitution, or created and established by law, except in regard to matters relating to the privileges, immunities and powers of Parliament and of its members, wherein the judicial power of the People may be exercised directly by Parliament according to law.” Prof GLP opines that the majority judgment constitutes “judicial overreach which has many undesirable consequences” including “traducing constitutional traditions; subverting the specific model of separation of powers reflected in our Constitution.”

Prof. GLP, is in effect advancing the view that the Sri Lankan Courts in the present constitutional framework of the 2nd Republican Constitution 1978 are subservient to the Executive or Parliament.

This view of Prof. GLP is, with respect, wrong on both constitutional principle and policy. There are no constitutional restraints on the judicial review of executive action in relation to declarations of emergency. Self-imposed judicial restraint may well constitute an abdication of judicial responsibility.

In our constitutional setting of checks and balances and judicial oversight it is the function of the Judiciary to review the legality of Executive action, including matters relating to the declaration of a state of emergency and Emergency Regulations

In our constitutional setting of checks and balances and judicial oversight it is the function of the Judiciary to review the legality of Executive action, including matters relating to the declaration of a state of emergency and Emergency Regulations

Unlike the Independence Constitution where a Separation of Powers (SOP) was found by judicial interpretation with the concomitant judicial power to even strike down post enacted legislation, the 1st Republican Constitution of 1972 explicitly did away with the concept of an SOP and instead whilst vesting sovereignty in the people, nevertheless made the National State Assembly the supreme instrument of state power exercising the Executive, Legislative and Judicial power of the people (vide Article 5). Resultantly the judicial review of enacted legislation was expressly done away with and instead pre-enactment review of a Bill tabled in Parliament by a Constitutional Court was provided for.

Indisputably this fundamental departure introduced by the 1st Republican Constitution was a direct response to the Queen V. Liyanage and the other judicial power cases where the Courts expressly recognised an SOP and the jurisdiction to even review the constitutionality of post enacted legislation.

But this doctrine of the abolishing of the SOP was subsequently abandoned, and one of the significant and welcome departures introduced by the 2nd Republican Constitution of 1978 was the explicit reintroduction into our constitutional framework of the principle of an SOP. This is made explicit by Articles 3 and 4 of the Constitution which vests Sovereignty in the people but proceeds to delineate how that sovereignty is exercised in terms of the trichotomy of the Executive, Legislative and Judicial powers and the further recognition of franchise and Fundamental Rights as also integral components of the sovereignty of the people.

Although the twin principles introduced in 1972 of a constitutional bar on the post-enactment review of legislation was retained together with the pre-enactment review of Legislation in the present 1978 Constitution, nevertheless the reintroduction of the SOP which guarantees the independence of the Judiciary is a fundamental feature of the present Constitution.

Although Article 4(c) of the present Constitution does state that “the judicial power of the People shall be exercised by Parliament through courts ... recognised by the Constitution … except in regard to matters relating to the privileges, immunities and powers of Parliament and of its Members, wherein the judicial power of the People may be exercised directly by Parliament according to law”, nevertheless there is a cursus curiae of judicial authority by the Sri Lankan superior Courts that have recognised both the concepts of the SOP and the independence of the Judiciary from Executive or Legislative encroachment.

Leading cases which have recognised an SOP include Premachandra V. Monty Jayawickrema (1994) 2 SLR 90 (SC) and the Supreme Court Determination on the 19th Amendment to the Constitution (2002) in which the author appeared as Junior Counsel to the late Deshamanya H.L. De Silva P.C. The Supreme Court has recognised that the independence of the Judiciary is an intrinsic component of the present Constitution in several cases including the Court’s Determination on the Industrial Disputes Act (Special Provisions) Bill 2022. In fact a more explicit pronouncement was made in Hewamane V. De Silva where the Supreme Court held that judicial power vested solely and exclusively in the Judiciary (1983) 1 SLR 1 at 20.

The explicit vesting in the Supreme Court of Sri Lanka under Articles 125 and 126 of the exclusive jurisdiction to interpret the Constitution and in respect of Fundamental Rights underscores the preeminent role of the Judiciary in our constitutional framework

The explicit vesting in the Supreme Court of Sri Lanka under Articles 125 and 126 of the exclusive jurisdiction to interpret the Constitution and in respect of Fundamental Rights underscores the preeminent role of the Judiciary in our constitutional framework

Moreover the explicit vesting in the Supreme Court of Sri Lanka under Articles 125 and 126 of the exclusive jurisdiction to interpret the Constitution and in respect of Fundamental Rights underscores the preeminent role of the Judiciary in our constitutional framework. Foundational principles of the present Constitution as recognised by our Courts include the Rule of Law, power is a trust, and there are no unfettered discretions in public law. Regrettably Prof. GLP assails these welcome advances made in our public law jurisprudence.

In our constitutional setting of checks and balances and judicial oversight it is the function of the Judiciary to review the legality of Executive action, including matters relating to the declaration of a state of emergency and Emergency Regulations. The duty of interpreting an Act of Parliament if a function of Courts and not of Parliament (Court of Appeal in C.W.C. V. Superintendent, Beragala Estates 76 NLR 1). The author cited this decision to the Supreme Court in challenging the Inland Revenue Bill introduced by the late Mangala Samaraweera. That Court reiterated this principle and, agreeing with the author, ordered a referendum on a particular Clause.

Even in the pre-independence period up to 1948 where vide powers were conferred on the Governor who exercised Executive authority, the Courts have unequivocally reviewed the legality of executive action as manifest by the significant decision of the Supreme Court in 1937 in “In Re. Mark Anthony Lester Bracegirdle”, where the executive act of the Governor of arrest and deportation of Bracegirdle to Australia was reviewed by the Supreme Court and quashed. This decision was a striking assertion of judicial independence and is the first significant judicial review of executive action.

Moreover, the recent ruling given by the Speaker in Parliament on 9 January 2026, on the Opposition Motion to appoint a Select Committee to review recent appointments made by the Judicial Service Commission (JSC) to the Judiciary further buttresses the explicit recognition of the SOP and the independence of the Judiciary. The Speaker reiterated the commitment of Parliament to the doctrine of the SOP and refused the Motion on the basis inter alia that Parliament was not hierarchically superior to the Judiciary and cannot be permitted to control the judiciary by creating an oversight mechanism with regard to the JSC.

(The author is a President’s Counsel and a Professor of Law)