Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Tuesday, 2 April 2024 00:50 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The UNP has always operated on a centre-right economic policy maxim, remaining on a continuum of Thatcherite or Reaganite low tax, small government, pro-business, pro-market foundations

Peter Breuer of the IMF’s visiting delegation made some interesting comments specifically related to alternatives or alterations to the current program. He stated that any alternative proposals must be realistic before repeating the urgency for improving revenue and meeting Intended Targets (ITs) and noting the “commitment in the (IMF) program to not grant any more tax concessions. Tax concessions are a missing component of tax revenues”.

Peter Breuer of the IMF’s visiting delegation made some interesting comments specifically related to alternatives or alterations to the current program. He stated that any alternative proposals must be realistic before repeating the urgency for improving revenue and meeting Intended Targets (ITs) and noting the “commitment in the (IMF) program to not grant any more tax concessions. Tax concessions are a missing component of tax revenues”.

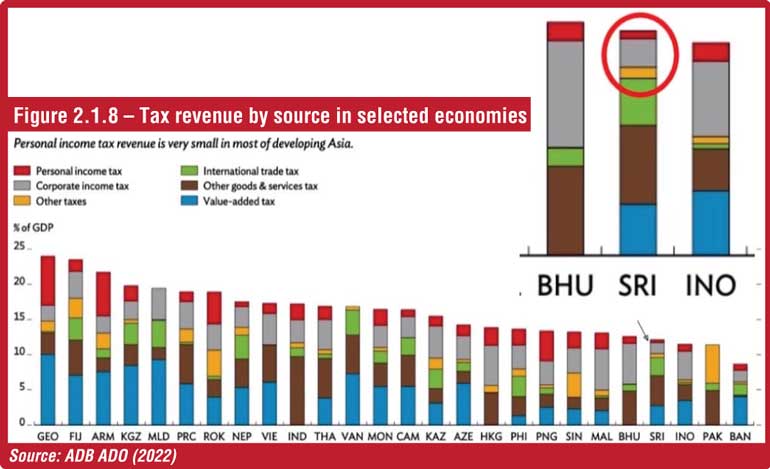

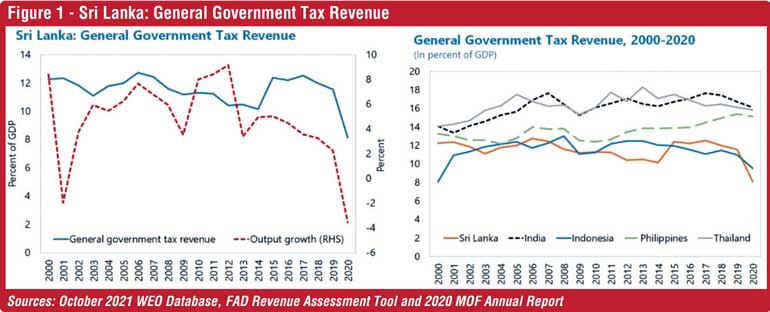

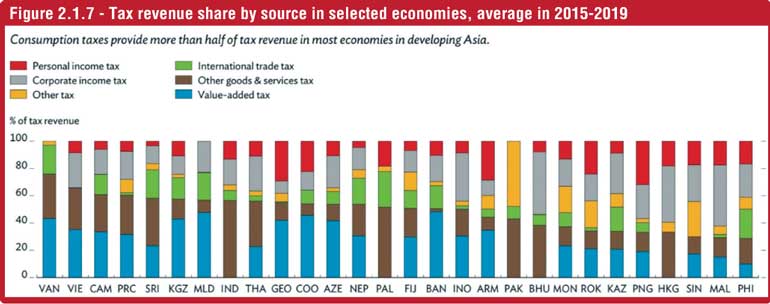

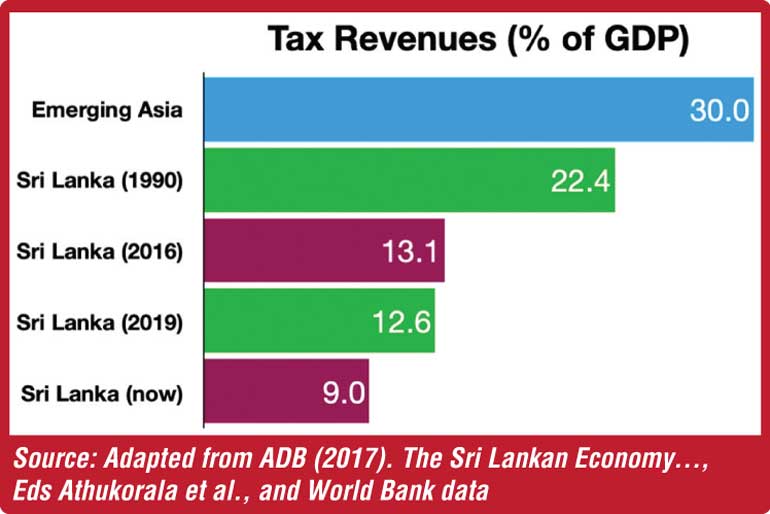

The given graphs extracted from ADB and IMF reports reiterate Breuer’s point that Sri Lanka’s tax revenues are inadequate in terms of value and imbalanced in terms of revenue source.

Former IMF Director Dr. Sharmini Coorey has been critical of Sri Lanka’s practice of providing long-term tax holidays, some as long as 25 years, to incentivise investments. At the Central Bank of Sri Lanka’s 73rd anniversary oration, Dr. Coorey utilised a version of a line made famous most recently by the writer Gore Vidal: “socialism for the rich, free enterprise for the poor” in her critique of corporate tax handouts.

This has been and will continue to be the ultimate challenge for all Sri Lankan governments, which have failed, over decades, to raise revenue to levels adequate to maintain its debt sustainability, social protections and fund a large and overblown bureaucracy.

Money and power

Reporting for the Sunday Times in March, Kapila Bandara noted treasury data revealing a list of Board of Investment approved companies that had received corporate income tax concessions amounting to Rs. 24 billion in just the 2022-23 period.

It is worth noting the industries and companies: “Apparel makers got Rs 5.26 bn corporate tax handouts on an aggregate tax base of Rs 50.18 bn and Rs 356 mn value-added tax concessions on an aggregate tax base of Rs 3.17 bn. Tourism companies got Rs 551 m, corporate income tax subsidies and Rs 83 m VAT concessions on an aggregate tax base of Rs 820 m”. Other industries included agriculture, services and utilities, power and infrastructure. The list of companies includes the multinationals Unilever, MAS Holdings and Brandix, but also David Pieris Motor Company, LAUGHS Eco Sri, Hemas Hospitals, Cargills, Confectionaires.

Further there are companies belonging to the Hayleys Group such as Hayleys Agro Biotech and a renewable energy project, Hayleys Neulwa Hydropower; an Araliya Group hotel, Daya Aviation and some others owned by industrialists that are embedded within power centres; some even sitting in Parliament. These are the relationships between private capital and public institutions that erode Sri Lanka’s corporate governance and create material weaknesses for the economy.

Tax holidays and incentives are common tools used by countries to attract foreign direct investment; the issue is that despite major tax incentives for Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) projects, Sri Lanka’s export base has been stagnant for quite some time, we have not diversified the export base, there have been no significant new sectors since the birth of the apparel sector of the early ‘90s. Tax holidays should not be granted in an ad hoc manner without transparent data showing how the positive impacts on the economy might outweigh lost tax revenue.

However, even more crucially, such tax holidays should not be maintained without reassessing the results of the existing structure of tax breaks; fresh tax holidays should not be granted without clearly defined deliverables. Especially in the context of an economic collapse precipitated by a fall in government revenue, while international financial institutions had been calling for revenue based fiscal consolidation for almost a decade.

Another glaring issue related to Sri Lanka’s FDI is the absence of sophisticated, global investments into high technology and tradable sectors; component manufacturing operations which might encourage technology transfers and integration into Global Production Fragmentation networks that span continents. Since the Covid19 pandemic, many of these networks have been diversifying away from China to mitigate single territory origination risks, shifting to India and other East Asian manufacturing giants like Vietnam and South Korea.

Many multinationals (Apple, Samsung, Toyota, Nike) assemble a single product in a factory with components manufactured in multiple countries, so called ‘manufacturing production fragmentation’; such operations account for significant trade flows.

Most recently, Sri Lanka’s FDIs have consisted of large companies from China with close connections to the Chinese State and are usually linked to infrastructure projects for China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Another investor that has entered into multiple projects including airport operations, infrastructure, ports and renewable energy, is India’s Adani Group, another company with very close links to political power centres in India.

This suggests that Sri Lanka still depends on some form of foreign political patronage to be able to attract foreign investments but why is it that only a very specific profile of company seems willing to make large investments on operations in Sri Lanka? What are the incentives driving such investments and keeping others away? Bandara notes the recent investments from China’s CHEH Port City Colombo (Pvt) which received a “25-year corporate income tax exemption under ‘strategic development project’. It was also given 10-year PAYE tax exemptions to 30 expat staff, among other benefits. Shangri-La Hotels Lanka (Pvt) Ltd enjoys 10 years’ corporate income tax holiday, followed by 6% rate for 15 years”.

Rigid ideologues

Part of the problem for Sri Lanka’s economy is that its policy seems to swing wildly between two disparate ideologies. The Sri Lankan centre-left, that is the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) and its wider People’s Alliance (PA); its latest incarnation, the Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP), the Marxist-Leninist Communist JVP and its alliance partner the NPP, all seem to have within their own spectrum, wildly different ideologies, I would argue that the common denominator is an under-appreciation of the dangers of fiscal largesse and a failure to appreciate concepts like investment returns and labour productivity.

However, the current IMF plan was also negotiated between the IMF and President Ranil Wickremesinghe, presumably in his capacity of Minister of Finance. I individualise the Sri Lankan side of the equation as this has been the narrative conditioned by the Government’s media and the President’s surrogates; this IMF deal was negotiated with significant direct input from Wickremesinghe.

Under such framing, some things become clearer. Firstly, that tax revenue to GDP is projected at 15% which is lower than the 20% Sri Lanka used to achieve by the early 90s. Our Tax to GDP is lower than the average in South East Asia, which is lower than the average for our global income peer group and still lower than the overall global average. This is why the IMF has been conditioning Sri Lanka to increase revenue; even during Wickremesinghe’s previous Government, the IMF requested that Sri Lanka urgently address tax revenue mobilisation.

I am a staunch critic of the Yahapalanaya Government of 2015-19 but consecutive Finance Ministers under that Government at least took steps to increase revenue. Controversial Minister of Finance, Ravi Karunanayake introduced a one-off super-tax on the major corporate income earners and Mangala Samaraweera later achieved consecutive primary account surpluses as part of the IMF program agreed by that Finance Ministry.

My contention is that this route was ultimately a failure due to being politically unpopular because it was too ideologically rigid. The UNP has always operated on a centre-right economic policy maxim, remaining on a continuum of Thatcherite or Reaganite low tax, small government, pro-business, pro-market

foundations.

Despite the aforementioned efforts of consecutive finance ministers, and even as successive IMF reports suggested further revenue based reforms such as broadening of the tax base, investing in the Inland Revenue Department, improving corporate income tax (CIT) by reducing tax holidays, altering the ratio away from indirect taxes, targeting the informal economy, introducing top marginal rates on income tax etc. etc. Even wealth taxes and capital gains taxes were part of the discourse from almost ten years ago.

Despite the best intentions of the 2018 Inland Revenue Act, that Wickremesinghe Government was only able to generate tax revenue at an average of around 11% of GDP during its time in office. This represents a failure to correct a most consequential imbalance that is crucial to Sri Lanka’s long-term economic viability, as stressed by international financial organisations.

Thatcherism lives on

Considering the lack of concrete measures taken to improve our tax to GDP ratio over two separate periods, the lack of ambition displayed by the revenue projections agreed upon with the IMF and the slow pace of implementing crucial revenue related reforms and investments, one must accept that Sri Lanka’s tax revenues are being held back by ideologues. Those who believe staunchly in the axiom of higher taxes being the problem in an economy, unable to conceive of taxation as part of the solution. The Centre-right believe taxation to be an imposition on human freedom, a restriction on enterprise, fundamentally undesirable and alien to capitalism and free markets.

Such an ideology, with Libertarian tendencies, belies the complex structures of modern societies that evolved with the emergence of nation states, through the industrial period and past devastating global conflicts. There is a long and well documented history of capitalism, trade, industry, labour and taxation all meeting at the intersection of the social contract. To conceive of taxation as being contrary to a functional, efficient system of free market capitalism is not only misguided but also ahistorical.

The idea of a society governed by a set of laws, necessarily requires a social contract but complications arise when political leadership indefinitely views government as being part of the problem, making it desirable to reduce the size of government. This is the central contradiction between the ideology of Ranil’s UNP and the project to develop Sri Lanka while preserving and strengthening the social contract.

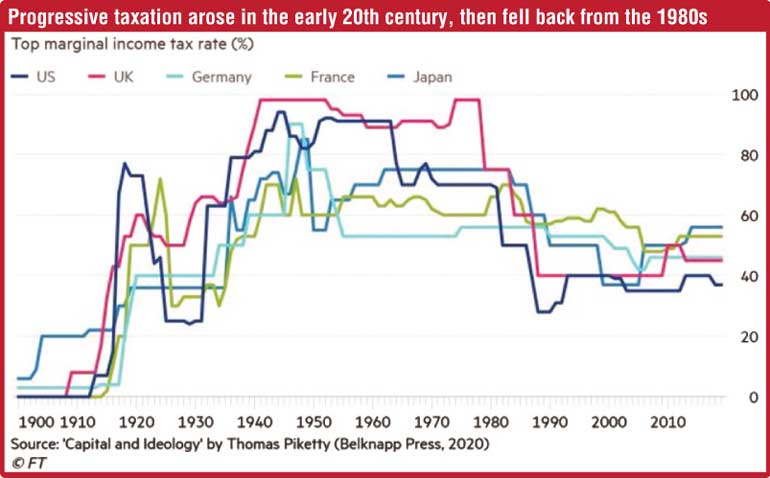

It is this dogma of the centre-right that has seen the public sector withdraw from various parts of the economy in favour of private investments in public utilities, education, housing, healthcare, transportation. This withdrawal has also coincided with a deterioration of progressive taxation around the world, including in developed countries.

As investments in public services reduce and as the prices of basic services, utilities, education etc. start to rise, you also see an increase in private debt levels which then leads to all manner of undesirable social outcomes.

This Wickremesinghe Government is making the same mistakes as previous iterations by not appreciating the importance of robust revenue reforms because, to some extent, it runs counter to their economic ideology. The substantial reforms required will seem too radical and extreme to the centre-right libertarian sensibilities of the President and his party; such notions are preventing Sri Lanka from raising more revenue, paying off debt faster, growing the economy through efficient spending and using new fiscal space to prioritise getting people back up on their feet. Thatcherism lives on and it is killing the Sri Lankan recovery.

References:

https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/784041/ado2022-theme-chapter.pdf

https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/journals/002/2022/341/article-A001-en.xml

https://www.sundaytimes.lk/240324/news/imf-advocates-property-tax-and-ending-corporate-freebies-amid-green-shoots-553075.html

https://ourworldindata.org/taxation

(The writer has 15 years of experience in the Financial and Corporate sectors after completing a Degree in Accounting and Finance at the University of Kent (UK). He also holds a Masters in International Relations from the University of Colombo. He is a media presenter, resource-person, a political commentator and Foreign Affairs Analyst. He also presents an interview show that is available on Instagram, Facebook and YouTube. He is member of the Working Committee of the Samagi Jana Balawegaya (SJB). He can be reached via email: [email protected]; Twitter: @kusumw.)