Thursday Feb 05, 2026

Thursday Feb 05, 2026

Thursday, 5 February 2026 00:35 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

India Supreme Court and Sri Lanka Inland Revenue Department

In the Tiger Global case (2026), the Supreme Court, deemed the transaction an “impermissible tax avoidance arrangement” under GAAR, pierced the corporate veil finding Mauritius entities as conduits (real control in US), and denied DTAA benefits despite TRCs. Gains from post-2017 transfers were taxable in India, overriding grandfathering if avoidance was the main purpose

In the Tiger Global case (2026), the Supreme Court, deemed the transaction an “impermissible tax avoidance arrangement” under GAAR, pierced the corporate veil finding Mauritius entities as conduits (real control in US), and denied DTAA benefits despite TRCs. Gains from post-2017 transfers were taxable in India, overriding grandfathering if avoidance was the main purpose

The recent Indian case of Authority for Advance Rulings v. Tiger Global International II Holdings decided by the Supreme Court in January 2026, underscores the application of general anti-avoidance rules (GAAR) to override tax treaty benefits under the India-Mauritius Double Taxation Avoidance Agreement (DTAA), denying capital gains exemptions for Mauritius-based entities deemed conduits/without substance for tax avoidance in indirect share transfers. The core of the Indian judgment reinforces the principle of «substance over form» and effectively grants tax authorities’ powers to scrutinise investment structures for substance and rational and potential tax avoidance, a stance that could influence tax jurisprudence in Sri Lanka and other nations.

The recent Indian case of Authority for Advance Rulings v. Tiger Global International II Holdings decided by the Supreme Court in January 2026, underscores the application of general anti-avoidance rules (GAAR) to override tax treaty benefits under the India-Mauritius Double Taxation Avoidance Agreement (DTAA), denying capital gains exemptions for Mauritius-based entities deemed conduits/without substance for tax avoidance in indirect share transfers. The core of the Indian judgment reinforces the principle of «substance over form» and effectively grants tax authorities’ powers to scrutinise investment structures for substance and rational and potential tax avoidance, a stance that could influence tax jurisprudence in Sri Lanka and other nations.

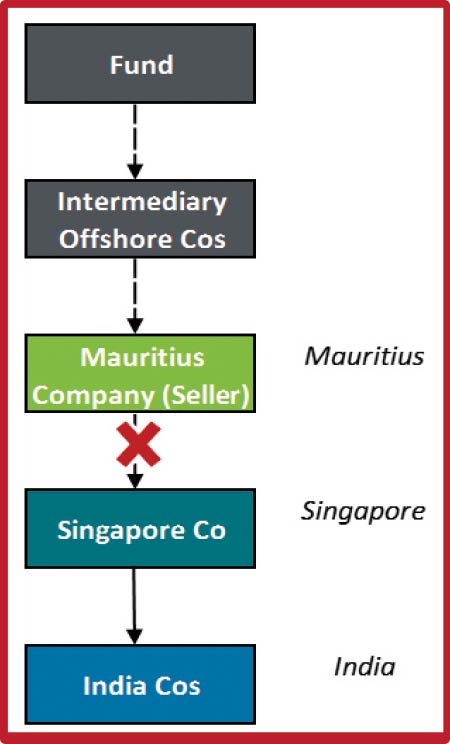

The key dispute was whether Tiger Global›s Mauritius-based entities could claim an exemption from capital gains tax in India under the DTAA for the sale of their shares in a Singapore-incorporated company (Flipkart) whose value was derived primarily from Indian assets.

Background

Investment and Sale: Tiger Global entities, incorporated in Mauritius, acquired shares of Flipkart Private Limited, a Singapore company which derived its value from India. As part of Walmart›s acquisition of Flipkart, the Tiger Global entities sold their Mauritius shares to a Luxembourg entity.

Tax Dispute: The Tiger Global entities sought a “nil” withholding tax certificate from Indian tax authorities in terms of the India tax law, claiming exemption under the India-Mauritius DTAA. The tax authorities denied the request in the form applied for and the Authority for Advance Rulings (AAR) went a step further concluding that the transaction was a prima facie tax avoidance arrangement and that the Mauritius entities lacked substance.

High Court and Supreme Court: The High Court overturned the AAR’s order, holding that the tax residency certificates (TRCs) were sufficient proof of residence, and that the transaction therefore could claim benefits under the DTAA. The tax authorities then appealed to the Supreme Court.

Supreme Court Ruling: The Supreme Court ruled in favor of the tax authorities, denying the DTAA benefits to Tiger Global.

The court’s key findings were:

TRC not conclusive: A Tax Residency Certificate (TRC) is only prima facie evidence of residence and not conclusive proof of entitlement to treaty benefits.

Substance over form: The court emphasised the «substance over form» principle, noting that the «head and brain» of the Mauritius entities lay with a US-based fund manager and that the entities were pass through without real decision-making power or significant commercial activity in Mauritius. The Courts adopted a “look through” principle allowing the authorities to pierce the corporate veil and investigate the “why” of the transaction.

GAAR overrides treaty: The General Anti-Avoidance Rule (GAAR) provisions of Indian domestic law can override even the DTAA when a transaction or an investment is concluded to be an «impermissible avoidance arrangement»

Grandfathering limits: Grandfathering provisions for investments made before 1 April 2017, protect genuine investments but not abusive arrangements structured primarily for tax avoidance. (The grandfathering rule under Indian tax law primarily applies to the Capital Gains tax on shares acquired pre 1 April 2017, being the date when the DTAA was amended to remove the capital gains tax exemption for Mauritian residents).

The Vodafone judgment

The Indian Vodafone judgment (2012) favoured the taxpayer, emphasising legitimate tax planning and refusing to impose tax on offshore transactions without explicit statutory backing. In contrast, the Tiger Global judgment (2026) sided with the tax authorities, applying anti-avoidance rules to tax such gains, marking a significant shift in India’s approach to cross-border tax structures.

In 2007, Vodafone (a Dutch entity) acquired shares in CGP Investments (a Cayman Islands company) from Hutchison Telecommunications International Ltd (also Cayman-based entity). This transaction indirectly transferred a controlling interest in Hutchison Essar Ltd (HEL), an Indian telecom company. The Indian tax authorities issued a show-cause notice, claiming capital gains tax under Section 9(1)(i) of the Income Tax Act, 1961, as the underlying assets were in India. Vodafone challenged this, arguing the sale was between two foreign entities outside India.

Both Tiger Global and Vodafone involved indirect transfers of Indian assets (telecom in Vodafone, e-commerce in Tiger) through offshore holding companies. The transactions were structured to leverage tax treaties or offshore jurisdictions (Netherlands/Cayman in Vodafone, Mauritius in Tiger) to minimise or avoid Indian capital gains tax. In each, the tax authorities argued the structures were conduits for tax avoidance, with real economic substance lacking in the intermediary entities.

Vodafone’s deal was a pre-2012 transaction without GAAR. Tiger Global deal occurred post-2017 DTAA amendments and GAAR implementation, with shares acquired pre-2017 but sold after. Vodafone involved a Netherlands DTAA (though the transfer was Cayman-based), while Tiger focused on Mauritius DTAA benefits. Control in Vodafone was disputed but not pierced; in Tiger, evidence showed US-based decision-making, with Mauritius entities having no real substance.

Both cases centered on whether India could tax capital gains from offshore share sales indirectly transferring Indian assets. Key questions included the applicability of Section 9(1)(i) (deeming income to accrue in India), treaty benefits, and piercing the corporate veil for tax avoidance.

Vodafone focused on interpreting Section 9 without retrospective amendments or GAAR. The court examined “look at” vs. “look through” approaches, treaty shopping legitimacy, and whether TRCs were conclusive for residency.

Tiger Global involved post-Vodafone changes, including 2012 retrospective amendments making indirect transfers taxable and GAAR, overriding treaties for avoidance schemes. The court scrutinised TRC sufficiency, grandfathering under amended India-Mauritius DTAA (Article 13), and substance over form.

In the case of Vodafone (2012), the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Vodafone. It held the transaction was not taxable in India, as Section 9 did not cover indirect transfers. The court upheld legitimate tax planning, rejected piercing the veil in the absence of fraud or sham, and affirmed TRCs as sufficient for treaty benefits. This emphasised investor certainty and “look at” the transaction holistically.

In the Tiger Global case (2026), the Supreme Court, deemed the transaction an “impermissible tax avoidance arrangement” under GAAR, pierced the corporate veil finding Mauritius entities as conduits (real control in US), and denied DTAA benefits despite TRCs. Gains from post-2017 transfers were taxable in India, overriding grandfathering if avoidance was the main purpose.

Vodafone represented an era of deference to offshore structures, while Tiger Global reflects India’s evolved, aggressive stance against perceived tax abuse, bolstered by GAAR and DTAA amendments.

The key dispute was whether Tiger Global’s Mauritius-based entities could claim an exemption from capital gains tax in India under the DTAA for the sale of their shares in a Singapore-incorporated company (Flipkart) whose value was derived primarily from Indian assets

The key dispute was whether Tiger Global’s Mauritius-based entities could claim an exemption from capital gains tax in India under the DTAA for the sale of their shares in a Singapore-incorporated company (Flipkart) whose value was derived primarily from Indian assets

Implications for Sri Lanka tax law

Implications for Sri Lanka tax law

General Anit Avoidance Rules (GAAR)

The Inland Revenue Act No. 24 of 2017 (IRA) also contains GAAR. It is primarily articulated in section 35. This section empowers the tax authority to counteract tax-driven arrangements.

The main provision of the 2017 Act, states that the Commissioner General of Inland Revenue can:

or any scheme that is not genuinely given effect to, if that transaction reduces or would reduce the amount of tax payable by any person.

The Act defines “scheme” broadly to include any trust, grant, covenant, agreement, or arrangement.

This rule allows authorities to look beyond the legal form of a transaction to its actual substance and deny tax benefits in instances of sham transactions or arrangements lacking genuine commercial purpose, even if they technically comply with the literal wording of the law.

Section 35 of the IRA is reproduced below for ease of reference:

This section shall apply where the Commissioner General is satisfied that –

Notwithstanding anything in this Act, the Commissioner- General may determine the tax liability of the person who obtained the tax benefit as if the scheme had not been entered into or carried out, or as if a reasonable alternative to entering into or carrying out the scheme would have instead been entered into or carried out, or that any transaction which reduces or would have the effect of reducing the amount of tax payable by any person is artificial or fictitious and can make compensating adjustments to the tax liability of any other person affected by the scheme.

Where a determination or adjustment is made, the Commissioner-General shall issue an assessment giving effect to the determination or adjustment.

The assessment made under subsection (3) shall be served within five years from the last day of the year of assessment to which the determination or adjustment relates.

For the purposes of this section –

“tax benefit” means –

The Act classifies shares in a non-resident company to a domestic asset of Sri Lanka if 50% or more of the said nonresident company’s value is derived directly or indirectly through one or more interposed bodies, from land or buildings in Sri Lanka. In this definition we see the embodiment of the substance over form mentioned in the Tiger Global case

The Act classifies shares in a non-resident company to a domestic asset of Sri Lanka if 50% or more of the said nonresident company’s value is derived directly or indirectly through one or more interposed bodies, from land or buildings in Sri Lanka. In this definition we see the embodiment of the substance over form mentioned in the Tiger Global case

Sri Lanka tax provisions relating to capital gains tax on share sale

The gain in relation to the realisation of a domestic asset of Sri Lanka is liable to tax. Domestic asset has been defined to mean:

It is pertinent to note under limb (d) the Act classifies shares in a non-resident company to a domestic asset of Sri Lanka if 50% or more of the said nonresident company’s value is derived directly or indirectly through one or more interposed bodies, from land or buildings in Sri Lanka.

In this definition we see the embodiment of the substance over form mentioned in the Tiger Global case. The section mentions that if substantial value (in the form of land and buildings) is derived out of Sri Lanka the asset (i.e. shares albeit foreign), is to be considered as a domestic asset irrespective of it being an indirect sale of shares of a local entity via a multi-tiered structure.

However, the Indian tax law contains more robust provisions vis-à-vis Sri Lanka income tax law in reaching out to tax indirect transfer of shares. The Indian law contains provisions that gives the taxing rights to India on indirect transfer of shares where the value is derived from India. Further it has also has a self-policing mechanism in the form of withholding tax. The onus is on the buyer of the shares to withhold taxes and adhere to the related compliance requirements in the event of an indirect sale concerning an Indian entity.

Conclusion

The Tiger Global judgment in fact laid out more broader guidelines using GARR as its base. It essentially observed the principle of “substance over form” which is a concept used widely in the interpretation of tax law. The Supreme Court of India agreed that the AAR was right in adopting the place of effective control and management in determining the place of residence of the company rather than merely relying on the TRC. Entities set up merely as conduits to obtain treaty benefits may now be rejected in the future.

The above ruling however does not necessarily mean that every multi-tiered structure is tainted. The facts of the case of each taxpayer will vary and the facts should be analysed carefully in the determination of substance and rational.

(The author is Partner – Tax Lead, Deloitte – Sri Lanka)