Friday Mar 13, 2026

Friday Mar 13, 2026

Monday, 9 February 2026 00:15 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The GREAT 2025–2030 Renewable Energy Project Development Plan approved by the Cabinet on February 2, 2026, aims to guide Sri Lanka toward a cleaner energy future, aligning with global decarbonisation efforts. However, significant gaps between its goals and the country’s institutional, infrastructural, policy, and financial capacities raise questions about its feasibility within the proposed timeframe.

The GREAT 2025–2030 Renewable Energy Project Development Plan approved by the Cabinet on February 2, 2026, aims to guide Sri Lanka toward a cleaner energy future, aligning with global decarbonisation efforts. However, significant gaps between its goals and the country’s institutional, infrastructural, policy, and financial capacities raise questions about its feasibility within the proposed timeframe.

Although dated December 2024, the plan received Cabinet approval only recently. The Ministry stated it was drafted by a committee from the CEB and SLSEA under the Energy Ministry Secretary. It is uncertain if other stakeholders, such as other Government agencies, the regulator, private sector participants, renewable energy industry, financial institutions, environmental organisations, or consumer representatives were consulted. It raises concerns about stakeholder support needed to achieve the plan’s goals.

Transmission bottlenecks and sequencing risks

At the heart of the plan’s limitations is its heavy reliance on transmission infrastructure that does not yet exist. The plan correctly identifies transmission as the single most critical bottleneck to large scale renewable energy integration. It assumes that a suite of large, complex, and capital intensive transmission projects will be completed on an accelerated schedule. Many of these projects remain unfunded, are in early conceptual stages, or depend on external lenders whose timelines are uncertain.

The plan front loads renewable energy additions between 2025 and 2028 while back loading transmission readiness to 2028–2033. This sequencing mismatch creates a structural vulnerability. Renewable plants may be built before the grid can absorb their output, leading to curtailment, stranded assets, and investor frustration. Sri Lanka’s historical record of transmission delays only heightens the concern that the plan’s timelines are more aspirational than realistic.

Operational and policy gaps in rooftop solar integration

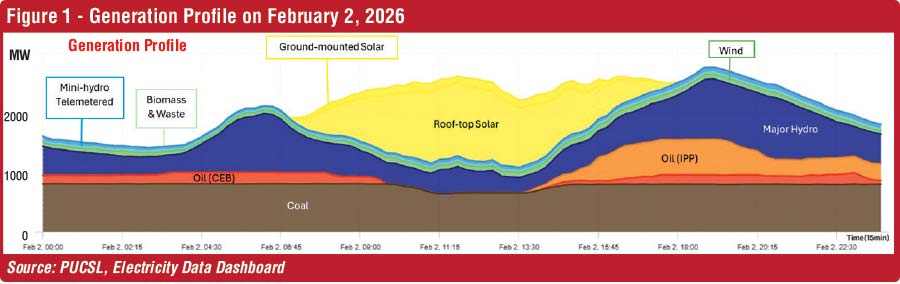

The plan’s treatment of rooftop solar further illustrates the gap between diagnosis and action. Sri Lanka had 1,700 MW of rooftop solar by mid-2025, much of it invisible to system operators, lacking telemetry, and installed with inverters that do not comply with modern grid support standards. Rooftop solar is now the major daytime power source (Figure 1).

The plan acknowledges that this legacy fleet is destabilising daytime demand and increasing the risk of system collapse during low load periods. CEB is curtailing solar production during periods of lower demand with no compensation to the producers. The plan offers no retrofit program, no enforcement mechanism for inverter standards, and no strategy for integrating existing systems into forecasting and dispatch. It does propose Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS). But CEB current efforts to procure BESS to absorb the peak solar production and use it during night times is massively delayed.

The plan prioritises future oriented measures such as smart meters and Distribution Control Centres, which, while important, do nothing to address the immediate operational crisis. If the proposed Time-of-Use (TOU) tariffs for rooftop solar are introduced, and consequently, the daytime purchase tariff rates are reduced compared to current levels, the rooftop solar sector will be adversely affected. There must be incentives to promote demand-side storage to store excess solar electricity to dispatch it at night.

The resulting plan recognises the near-term problem but declines to solve it and even exacerbates the problem.

Logistical weaknesses in solar and wind resource development

Logistical weaknesses in solar and wind resource development

The resource development strategy, particularly for solar and wind, is technically sound but logistically fragile. The zonal mapping is robust, and the identification of high potential regions such as Mannar, Kilinochchi, and the Northeastern wind and solar belt reflects strong analytical work. However, nearly all major projects depend on transmission corridors that are delayed or unfunded. The plan also continues to promote additional ground mounted solar despite acknowledging that solar capacity has already exceeded the requirements of the Long Term Generation Expansion Plan. Offshore wind, a promising long term opportunity, is mentioned but not meaningfully integrated into the 2025–2030 horizon. The resource strategy is therefore strong in theory but constrained by the absence of enabling infrastructure.

Gaps and delays in the storage implementation plan

The storage roadmap suffers from a similar disconnect. Most surprising is the observation that the need for Battery Energy Storage Systems and pumped hydro storage has been delayed, while in reality CEB is already curtailing solar and wind production because of the supply and demand mismatch.

The plan does not quantify the minimum storage required to stabilise the grid under high renewable penetration, nor does it compare the cost effectiveness of storage against alternatives.

The plan does propose multiple BESS and a 600 MW pumped storage plant, but years into the future. One project, the 100 MW Kolonnawa BESS, has secured financing. All other storage projects require land, environmental approvals, and multi year procurement cycles that extend well beyond the plan’s timeframe. The Maha Oya pumped storage plant, slated for commissioning in 2034, lies entirely outside the planning horizon. The result is a storage strategy that is ambitious but not anchored in analytical rigour and not actionable.

Digitalisation gaps undermine renewable grid integration

Digitalisation, a foundational requirement for modern grid management, is treated as a secondary technical enhancement rather than a prerequisite for renewable expansion. The proposed Renewable Energy Control Desk will not be operational until mid 2026, already late relative to the rapid growth of rooftop solar. While this is a nod towards reality, it is doubtful that the aspirational June 2026 timeline can be met.

The plan does not specify funding or procurement pathways for Distribution Control Centres, nor does it establish national standards for inverter interoperability. Without these elements, the grid will continue to operate with limited visibility and control, undermining the very renewable targets the plan seeks to achieve.

Demand-side management: Policy gaps and analytical shortcomings

Demand side measures, such as Time of Use tariffs, daytime industrial promotion, and EV charging incentives, are conceptually promising but analytically underdeveloped. The plan offers no modelling of expected demand shifts, no assessment of tariff impacts on consumers, and no analysis of industrial competitiveness. These interventions remain policy slogans rather than actionable tools for reshaping load curves.

Environmental vulnerabilities overlooked

The Plan overlooks critical environmental sensitivities. The plan does not evaluate risks such as biodiversity loss, migratory bird corridors, forest fragmentation, land-use conflicts, or social-ecological conflicts. It does not compare the relative enviro-social impacts of conventional and renewable technologies to inform choices. It does not offer technical solutions such as bird-safe wind turbine design, migration curtailment protocols, or radar shutdown systems. This is naive and shows little recognition of the recent delays and cancellations of Mannar wind developments due to opposition from environmental groups.

Environmental review is addressed only after sites are selected, relegating EIAs to a late procedural step rather than an integral factor in site choice or project planning. The lack of cumulative impact assessments is especially concerning for sensitive areas like Mannar.

Land and social-environmental issues receive minimal consideration; ecological sensitivity, displacement, land-use conflict, protected areas, and religious and cultural sites are overlooked. Land acquisition is presented as a formality rather than a way to protect environmental and social assets.

Consequently, the strategy lacks credibility and threatens realising the goals.

Governance challenges: Institutional fragmentation and reform needs

Perhaps the most significant non technical weakness lies in governance. The plan assumes seamless coordination among CEB, SLSEA, PUCSL, and the Ministry of Energy, despite a long history of institutional fragmentation, overlapping mandates, procurement disputes, and political interference. The plan does not propose a unified permitting authority, a single window clearance system, procurement reform, timely environmental and social assessment, or streamlined land acquisition processes. The challenges are amplified as the CEB is presently undergoing major restructuring. Without governance reform, even the most technically sound strategies will falter.

Financial planning deficit: Absence of a viable funding framework

Finally, the plan lacks financial and economic justification. It lacks a credible financial strategy. It lists dozens of projects requiring billions of dollars but provides no consolidated investment estimate, no financing roadmap, no debt sustainability analysis, and no model for mobilising private capital. In a country facing severe fiscal constraints, this omission is not merely a gap, it is a fundamental flaw.

Charting a path forward: Turning ambition into achievable progress

Sri Lanka can achieve its renewables goals, but success depends on moving from a technology-driven approach to a more practical, well-rounded plan with careful follow-through. The GREAT plan should be based on realistic expectations instead of wishful thinking. Environmental and social protections need to become a central consideration, truly guiding the development of future projects.

Achieving success requires comprehensive and inclusive consultation extending beyond CEB and SLSEA to incorporate other Government agencies, the PUCSL, private-sector stakeholders, renewable energy developers, financiers, environmental organisations, and consumer representatives. These groups will play pivotal roles in investing, developing, operating, regulating, and ultimately adapting to the transition.

By focusing on capacity, governance, stability, stewardship, and true stakeholder engagement, and backed by thorough analysis, the Government can turn plans into a credible roadmap and make Sri Lanka’s clean-energy transition both ambitious and achievable.

(The author Former Lead Energy Specialist, World Bank, Washington DC, USA)