Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Monday, 8 July 2019 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Sri Lanka is now an upper middle income country

The World Bank, in its 2019 country classification release, has elevated Sri Lanka from a lower middle income country to an upper middle income country. This has been based on the average income of a Sri Lankan, known in economic parlance as the gross national income or GNI per capita, passing the threshold of $ 3,996 set for upper middle income countries. As at 1 July 2019, a Sri Lankan on average has earned an income of $ 4,060, a little above this threshold, thereby making Sri Lanka eligible to join the upper middle income country club (available at: https://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/new-country-classifications-income-level-2019-2020?fbclid=IwAR3gkSoxhIjTSuxJzaLmwI6rMKhLwOY-vT_-vIVutL1OoW_AQuvcuqw5Dww).

Use of GNI in place of GDP to measure economic advancement

The World Bank uses GNI per capita and not the more popularly known Gross Domestic Product or GDP per capita for classifying countries into different stages of economic advancement. That is because GNI includes all the incomes earned by peoples of a country irrespective of whether they are resident in that particular country or not. In contrast, GDP measures the incomes earned by all within the territory of a country irrespective of whether they are citizens or not. Hence, GNI pertains to the people of a country and therefore is a better indicator of the wellbeing of such people. For international comparison, the World Bank converts GNI per capita measured in the local currency into US dollars by using an average exchange rate.

Atlas method

That rate is the average exchange rate of the currency of the country against the US dollar for the last three year period adjusted for local inflation. This conversion method is technically called ‘The Atlas Method’ because it is the method used by the Bank to present data in its World Development Atlas. This precludes the distortion of the exchange rate at least to some extent due to manipulation by governments or spikes in the rate due to temporary market developments. While this measure has its own limitations, it is considered a better measure than alternatives available. The details of the measurement can be found at https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/378831-why-use-gni-per-capita-to-classify-economies-into . In the case of Sri Lanka, because of the high interest payments and profit transfers made to foreigners, GNI is lower than GDP by about 3%.

The present elevation in the status is encouraging

Despite these limitations, this attainment by Sri Lanka is certainly encouraging. But it also exposes the country to a few challenges.

It is encouraging because Sri Lanka, after 22 long years since it was promoted from a poor country to a lower middle income country by the World Bank in 1997, has now been able to pass one of the two hurdles in its way to become a rich country. Since independence in 1948, Sri Lanka had remained a poor country for 50 years because of its low economic performance at slightly more than 4% per annum. This was a derogatory tag attached to Sri Lanka, but in 1997, it was able to shed that tag when it earned an average income of $ 786 per person. But because of a little higher economic performance after 1997, it did not take 50 years for the country to pass the next hurdle. In fact, that hurdle was passed after 22 years. Hence, the present attainment is encouraging.

Such an attainment in which a country has become richer than before should make its people happier. However, in this case, there are two qualifications which diminish the real value of this attainment.

Need for removing price increases

One is the price increases that have contributed to increase the money income of people during this period. That would have been corrected had the rupee been allowed to fall correspondingly against the US dollar, the currency used to convert the income measured in rupees to a globally comparable yardstick, to the extent Sri Lanka’s average inflation was higher than the average inflation of its major trading partners. The second is the income disparity among Sri Lankans as well as across provinces in Sri Lanka which makes some people or provinces richer, while the others remain laggards.

An element of overvaluation in the exchange rate

During 1997-2018, Sri Lanka’s economy had grown on average at about 5% per annum in real terms. This growth rate is not sufficient to push the income levels of people to the minimum needed to cross the threshold of the upper middle income category within 22 years. However, there have been increases in price levels at about 13% per annum on average boosting people’s rupee incomes. To consider such increases in money incomes as a real improvement of people’s wellbeing is an illusion. Hence, the illusive effect of price increases should be corrected by allowing the exchange rate against the US dollar to fall in the market.

• As long as only an exclusive few would benefit from economic growth, nationally or provincially, all others are denied of enjoying its fruits. It leads to the creation of economic, social and political tensions among citizens. These tensions become a fertile ground for crafty leaders to exploit people’s dissatisfaction for their personal benefits.

• There is a set modus operandi used by these leaders to attain their goal. A fictional enemy who is both illusive and elusive is created and shown to dissatisfied people as the cause of their suffering. With a promise to end the suffering, they are mobilised against this enemy. In most cases, the enemies are ethnic or religious minorities who are projected as a group enjoying a better life at the expense of the majority people.

• Political leaders throughout history have survived and prospered by creating conflicts among their own citizens. When doing so, they usually misrepresent nationalism as equivalent to patriotism. A patriot will fight for his ethnic, caste or religious group. In contrast, a nationalist will fight for the wellbeing of all humans. Hence, while patriotism impedes economic prosperity, nationalism will be a beneficial causal factor for same. Accordingly, a country which is divided on ethnic or religious lines fails to mobilise the efforts of all citizens for generating prosperity. One important causal factor for the low economic growth in Sri Lanka in the post-independence history has been the division of people on ethnic or religious grounds.

If it had not been allowed to happen, the result is the overvaluation of the rupee against the US dollar, the currency which is used to convert the income in rupee terms to an internationally comparable measurement. During 1997-2018, the rupee has fallen in value against the US dollar by about 3.4% annually. It appears that this depreciation has not been sufficient to push the rupee value down to reflect the true value of the incomes converted to dollar terms. To correct this, the World Bank has used the average rupee-dollar rate for the previous three year period, but there is still an element of overvaluation of the rupee built into that formula. Hence, the overvalued rupee would make such incomes higher than what they should have been. As such, Sri Lanka may have attained the upper middle income country status faster than the period it would have normally taken.

The World Bank also recognises the deficiency of using per capita income to gauge the wellbeing of people due to income disparities. This is particularly relevant in the case of Sri Lanka due to two reasons.

Uneven income distribution

First, historically Sri Lanka has had an uneven income distribution among its citizens. According to the Household Income and Expenditure Survey conducted by the Department of Census and Statistics in 2016, 51% of the country’s income has been earned by the richest 20% of citizens. In contrast, the poorest 20% has earned only 5% of the total income. Incomes in Sri Lanka have normally been concentrated at high income earners. This is shown by the fact that the top 30% has bagged 62% of the total income in 2016, while the poorest 30% has got only 9% of the total income. The middle income earners have got only 29% of the total income. With this uneven income distribution, it is questionable whether the elevation of the country to upper middle income status would really mean an improvement of the welfare levels of people in general.

Uneven provincial income distribution

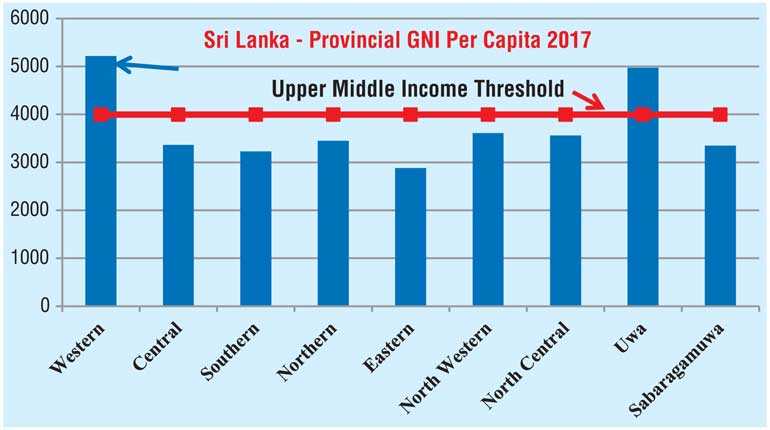

Second, the disparity of incomes earned by different provinces in Sri Lanka is more prominent than the overall uneven income distribution. The provincial GDP numbers are calculated by the Central Bank after the Department of Census and Statistics compiles the national GDP numbers. Hence, there is a time lag in getting provincial GDP numbers and the latest available has been in respect of 2017. These numbers were converted to GNI numbers by this author by using the national level disparity of 3% between GDP and GNI.

The results are presented in figure 1 along with the threshold limit of $ 3,996 applicable to upper middle income countries. According to these data, only the Western Province and the Uva Province have qualified to join the upper middle income country club, while all other provinces have to further grow in order to earn that status. If Sri Lanka grows at a rate of 5% per annum in the coming years, it would take at least another eight years for the whole country to earn the status of an upper middle income country.

The exploitation of people’s dissatisfaction by crafty leaders

Sri Lanka’s present challenge is therefore to eliminate the provincial disparity in income levels in order to reap the full benefit of being an upper middle income country from the wellbeing point of its citizens. For that purpose, it is necessary to adopt a policy strategy to generate even economic growth across all the provinces. As long as only an exclusive few would benefit from economic growth, nationally or provincially, all others are denied of enjoying its fruits. It leads to the creation of economic, social and political tensions among citizens. These tensions become a fertile ground for crafty leaders to exploit people’s dissatisfaction for their personal benefits.

Creation of an unseen enemy

There is a set modus operandi used by these leaders to attain their goal. A fictional enemy who is both illusive and elusive is created and shown to dissatisfied people as the cause of their suffering. With a promise to end the suffering, they are mobilised against this enemy.

In most cases, the enemies are ethnic or religious minorities who are projected as a group enjoying a better life at the expense of the majority people.

In Nazi Germany in mid 1930s, the enemy was the Jews. In Myanmar today, it is Rohingya, a minority Muslim group living at the margin of the economic system. In Bangladesh, it is minority Buddhists. Among the majority Buddhists in Sri Lanka, it is Muslim or Tamil minorities. In Burkina Faso, it is the Christian minority among the majority Muslims. If there are no potential minorities, then, the enemy is invariably the rich people in the country.

Political leaders throughout history have survived and prospered by creating conflicts among their own citizens. When doing so, they usually misrepresent nationalism as equivalent to patriotism. A patriot will fight for his ethnic, caste or religious group. In contrast, a nationalist will fight for the wellbeing of all humans. Hence, while patriotism impedes economic prosperity, nationalism will be a beneficial causal factor for same. Accordingly, a country which is divided on ethnic or religious lines fails to mobilise the efforts of all citizens for generating prosperity. One important causal factor for the low economic growth in Sri Lanka in the post-independence history has been the division of people on ethnic or religious grounds.

Have megapolis scheme in all provinces

The present resource allocation strategy in Sri Lanka has overwhelmingly favoured the Western Province. A Megapolis scheme aiming at diverting resources to the tune of $ 45 billion over the next five years for the development of the Western Province has been launched.

The underlying economic logic has been that the fast development in the Western Province will generate similar development in other parts of the island due to economic linkages and interdependence. For instance, those in Ampara District will stand to benefit from the high incomes earned by those in the Western Province by creating a safe market for their food, dairy and fish products.

However, this will not happen automatically unless there are conscious policies to link these two markets via access roads, logistical facilities and technological improvements. If these are not present, those high income earners will seek to satisfy their demand from markets in Kerala or Tamil Nadu which are closer by air to Colombo than to Ampara or Batticaloa. What this means is that similar Megapolis schemes have to be initiated in other parts of the island as well.

Goal should be to generate shared prosperity

The goal of economic development efforts by world nations today is to generate ‘shared prosperity’ among its citizens. At a global level, this is further expanded to include all the nations in the world. As such, economic development in India or China should generate similar prosperity in other nations as well. It would ensure that the fruits of economic development will not be enjoyed by an exclusive group of people or countries. It should invariably be an inclusive development in which all the citizens irrespective of location, ethnicity, religious faith or caste can participate in growth efforts and enjoy its fruits without any discrimination.

Thus, to make Sri Lanka’s elevation to upper middle income country status meaningful, it is necessary to ensure that growth generates shared prosperity to all.

(The writer, a former Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, can be reached at [email protected].)